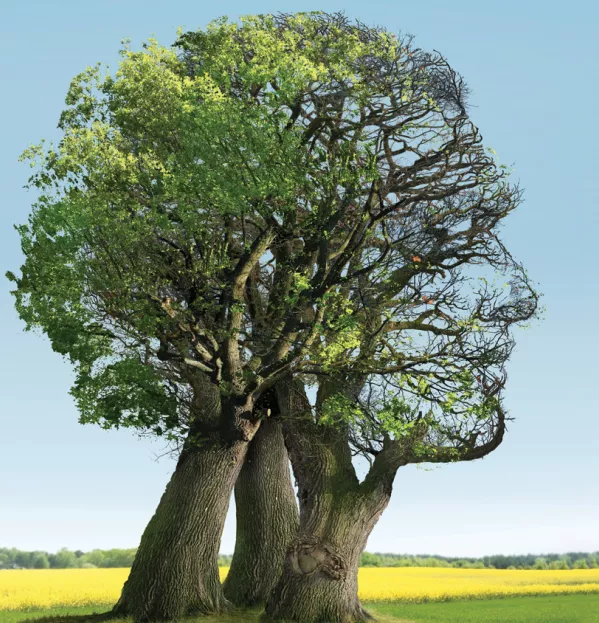

Growing a mental health strategy

You know you are sitting on a mental health problem in your school when you repeatedly see the following scenarios: a student, feeling overwhelmed with school pressure, rushes out of class with a panic attack; another hangs around your class after the lesson because he just needs to talk; a student’s weight is beginning to dominate her life; or a 15-year-old boy is displaying serious, defiant antisocial behaviour and violation of the rules.

These are not uncommon problems in schools, but we tend to view them as isolated incidents rather than a connected group of behaviours that need to be tackled with a cohesive, overarching strategy.

We decided to create such a strategy, putting in place a programme that seeks to help students to be literate about their mental health, and to make informed choices about their emotional and physical wellbeing. Here’s how we did it.

1. Make it official

We made tackling mental health part of our school development plan, with targets for both staff and students. This meant we had a whole-school vision, but also that we were accountable to those targets and reporting on progress was built in from the start.

2. Decide the role you will play

We recognised that our role was not to diagnose but to be pre-emptive. School staff did not try to replace child and adolescent mental health services. We saw our role as:

- * Raising awareness of what mental health is and its related illnesses.

- * Learning the signs to look out for and giving advice for students to be able to support themselves and seek help.

- * Creating an inclusive environment that did not discriminate against students facing mental health challenges, but instead sought to find ways to promote emotional literacy, resilience, optimism, generosity, appreciation, healthy physiology, social connection and growth mindset.

3. Appoint leaders

We appointed staff to lead on mental health support. These adult wellbeing mentors have training in youth mental health and are experienced in delivering non-directive supportive therapy. They are available to students at all times.

4. Clarify aims

We separated mental health and special educational needs support. We let students know that learning needs and mental health needs, although often linked, were essentially different; we have two different spaces and different staff allocated. In this way, we hope to profile and start vital campaigns, such as #TimeToTalk, in our school.

5. Make it interactive

We started at the top, by surveying teachers’ response to mental health and wellbeing in the workplace. We then created a “You said, we did” response to it; offered free weekly in-house yoga classes; training to introduce mindfulness; and ran a course to get staff started. We introduced a room for staff for quiet reflection and ran a mental health panel with a cross-section of staff over the course of the year to feed back on the research results. It was out of this panel that a staff wellbeing action group was formed.

Our student voice was ascertained through a comprehensive project with an external researcher. The qualitative data was gathered from focus-group sessions. These results then informed the type of detailed questions we asked in the questionnaires as we gathered the quantitative data. Based on the initial results, we were then able to make informed decisions about what our students needed in each year group and as a school.

For example, most of our student results revealed that:

- * They did not always know where to get support for mental health.

- * They did not know who to talk to.

- * They felt the amount of information online was overwhelming.

Out of this, we created a wellbeing zone. This space was transformed with murals, information and signposting, all with a view to welcoming our students to a place where we get to talk about issues affecting mental health. There are four spaces: an anti-bullying pop-in room; a wellbeing pop-in room; “club chill” - an invitation-only lunchtime room specifically for our most vulnerable to hang out; and the wellbeing centre for private meetings by appointment with adult mentors. The students can self-refer at lunchtime or they can be referred by a staff member.

We already had a successful peer-mentoring anti-bullying ambassadors programme, so using the same model, we created wellbeing ambassadors. These have been trained by relationship-support charity Relate and offer a lunchtime listening service, focusing on empathy rather than giving advice, although they are in a position to signpost further support in the school or online.

Another thing we created was a free student-led mental health and wellbeing app, My TeenMind. On the app, students have all the key information they need on the various topics of mental health; it clearly lets them know where they can go in the school and who they can talk to.

The provision of this digital support, along with lots of physical signs throughout the school, ensures that our students now have easy access to the information they need.

We will build on our progress this year, rolling out our own in-house My TeenMind mental health qualification. Every Year 7 student in the school will be expected to complete a series of lessons in personal, social, health and economic education, and will be given a mini assessment. This will provide evidence and ensure that the students are all completely literate on mental health before they reach Year 8.

6. Engage parents

We engaged parents by starting up a parent wellbeing-ambassadors group. It is visible as a Twitter community (@wellbeingparent), and they will be volunteering their skills to the school to aid the ethos of wellbeing. It could be anything from breadmaking classes for students and their parents to acupressure massages for staff. They will also be helping us to run a new project in this new year with a local charity, involving drop-in coffee mornings for parents to come and talk about mental health and their families.

They are a key driving force behind the whole-school #familyMH5aday campaign, for which we will be rolling out initiatives during the academic year.

After one year, what effect has this had? It’s led to the best set of attendance figures we have ever achieved; a busy wellbeing zone at lunchtimes; a growing number of student applicants to become ambassadors; a growing number of proactive parents who want to come on board; greater awareness of what is good mental health; greater awareness of support available in the school and the community; and our best-ever set of school results.

Clare Erasmus is head of mental health and wellbeing at the Magna Carta School in Surrey

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters