Helping SEND pupils to cross the employment divide

Until two years ago, I was the wondrously and uniquely entitled chief master of King Edward’s School in Birmingham. Once a direct grant school, now an independent school, it is the alma mater of Edward Burne-Jones, JRR Tolkien, and two Nobel prizewinners, as well as Lee Child and Bill Oddie.

About eight years ago, I was invited, because of my grandeur, by the authorities of the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference, to talk about headship to a new generation of school leaders at an induction weekend. I turned up one Saturday morning at a rather plush country-house hotel, lurking in the middle of Middle England, and my youngest son, Sam, came with me.

Sam was about 10 at the time and, so that he might feel involved, we gave him the role of pressing the button on the laptop for my presentation. He knew that I had 20 slides, each containing one bitter lesson or sacred truth about headship. After about half an hour of my eloquence, we reached the eighth slide and Sam said, cheerfully, “Only 12 to go, Dad.” It was the biggest, perhaps the only, laugh of the morning. At the end, the new heads applauded and Sam took a bow, delighted by his contribution. I expect none of the heads there that day will remember a word I said, but they will still remember Sam.

Now, Sam is autistic. He is happy and autistic, sociable and autistic, and he has had the great good fortune of growing up in a close, friendly, understanding school community. But he is autistic. He attends Selly Oak Trust School, a special school where 383 pupils arrive every morning, many of them in the 28 minibuses that travel from all over Birmingham.

The range of needs at the school is enormous and has grown wider in recent years - the average cognitive age of the children on entry at 11 is between 5 and 6. The facilities - part faded 1960s school architecture, part Portakabins - don’t bear close scrutiny, especially for someone who has spent his life in the cloistered calm of independent schools.

However, the provision and the commitment of the staff - under their Great Leader, Chris Field - are truly remarkable. It is, for example, the only special school with a Combined Cadet Force, so Sam and his peers have sailed and rowed and marched, and had the chance to go on tall ships in the Channel and Royal Navy boats off Liverpool, and visited the battlefields of the First World War and D-Day. Sam’s best academic subject is maths and he is the justifiably proud owner of both a D in the old currency GCSE and a 3 in the new money GCSE.

He also has an encyclopedic knowledge of obscure subjects - German tanks, US gangsters and fighter pilots - and a capacity to spontaneously come up with jokes better than any you’ve seen in a cracker: “If a choir went on tour to Alsace, would it be singing in Lorraine?”; “Where do you learn how to get on a plane? Boarding school.” It’s nice to think that, somehow, he has inherited his maternal grandfather’s sense of humour.

And yet, for all his qualities, he cannot pass the most basic functional skills qualification in English. Nor, for all his knowledge, could he write a sentence in a GCSE history exam.

‘What will become of them?’

Eight years have gone by since Sam’s highlight near Hinckley. He is now 18 and in Year 13. Soon the excellent Selly Oak Trust School will no longer be able to provide for him or his contemporaries. It’s a moment that looms larger and larger in the minds of the parents of autistic children - or any parents of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). They have spent years caring for a child, but now the question is, what will become of their young adult?

The reality parents worry about goes like this: according to Mencap, just 6.6 per cent of people with learning disabilities are in paid employment in the UK, whereas 65 per cent of such people would like to work. The figures for autistic adults are different but not that different: just 16 per cent of autistic adults are in full-time paid employment, with 32 per cent in some kind of paid work, even though only half of autistic adults actually have a learning difficulty.

Since this is so, the likely fate of the majority of these young people is that they won’t go on to work but instead some different form of education, often for years. However, it is rare that this continued education increases the chances of employment: too often it hides or postpones the problem. And then, after the age of 25, there is little or nothing to be done.

At that moment, these young adults run the risk of a lack of purpose or activity as well as social isolation. Very often they will be back at home, if they have a home, with little to do, or in some kind of care. Hence, I suppose, the deeply worrying statistics about the mental (and physical) health, even life expectancy, of those with learning difficulties. And this will often have an impact on the whole family, which now has to take on the full responsibility that was shared during the years of education. One of Sam’s autistic friends has six GCSEs and is much more able academically than Sam, but his mother, a very experienced doctor, has decided to give up her job in order to better support her son as he passes into adulthood. That is the very opposite of the way we tend to think about the duties of a parent. And this is no small matter: 1.5 million people in the UK have a learning disability; there are 700,000 people who are autistic, of whom half have learning difficulties.

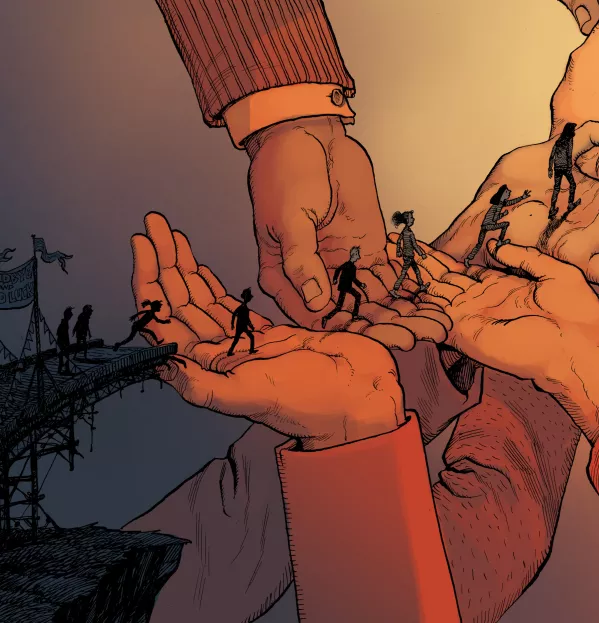

So, there is a problem, a deep and sad problem, not least because these young people want to feel normal, to feel that they belong and have a role. How can children with learning difficulties cross the divide from their separate, specialist education into meaningful, fully adult work and life?

Well, I believe that there are some solutions. I will offer two that are working now and, at the end, I will make the modest proposal that schools - “normal” schools - might be a big part of the answer.

So, here is one solution. Communicate2U is an enterprise based at Coventry University that works with Selly Oak Trust School. It starts with the premise that the “normal” world must be willing to learn and understand, rather than exclude. That “normal” world runs on a word-based system of critical thinking, which is precisely what makes things hard for those with learning difficulties. So, Communicate2U takes senior students from Selly Oak, often with very high needs, and enables them to be part of the delivery of courses to 800 health and social care students about communicating with people who have learning difficulties.

The benefit for the health and social care students is obvious: it prepares them for their future work. And the benefit for the Selly Oak students is also obvious, but even more immediate: they are the ones who are doing the teaching of “normal” adults, and they are growing in experience and confidence, travelling out of school, and working in a different place with different people.

Here’s another solution: the supported internship. It comes in different sizes and flavours but, at Selly Oak Trust School, it goes like this. Through a national organisation called EmployAbility, the school has forged a link with a National Grid office. Each year, this office takes on four Year 14 students and gives them, in effect, a year’s work experience in three different areas of the business.

The set-up works for a lot of reasons. National Grid wants it to work. The staff want it to work, and know what to expect and what to do. The four students are prepared for the change in their final year at school and are supported by two full-time job coaches, who are themselves school staff. Each day, from their job coaches, students also receive teaching in English, maths and a BTEC so that their academic progress continues. The four students have twin anchors: they still feel part of the school while at the same time going out to work in a “proper” job in the “real” world. And it costs neither the school nor National Grid anything. The students are, like so many student interns these days, working for free, and the job coaches are government-funded.

A lot to offer

It really does work, even if it’s not always perfect: last year, three of the four students from Selly Oak Trust School were retained in permanent part-time jobs at National Grid. Even if that does not happen, those students are ready for employment elsewhere. Across all such programmes in the country, 60 per cent of supported interns achieve paid employment: that’s a long way from the dire 6.6 per cent figure mentioned earlier

Here is my modest proposal. “Normal” schools (state schools, independent schools) could provide precisely the environment in which such young adults could prosper on supported internships. All 18-year-olds who are autistic or have learning disabilities are different. However, in their many ways of being and relating, they have much to offer. For example, autistic young people are often reliable, conscientious and utterly trustworthy. They like order and routine and everything in its place - rare virtues in an adolescent. They are at their best where people are working in small, cooperative, ordered groups in an environment that is friendly, cheerful and structured: the sort of groups that are common in our schools.

These young adults know how schools work and schools are meant to be good at looking after the young. Schools also have a wide range of jobs that interns could undertake, in catering, grounds, portering, administration. Nor would it be hard for a “normal” school to collaborate with a special school to make this work - and just think of the impact the schools sector could have on such a huge problem.

The benefit for these young people would be obvious, and surely schools, even if they do not educate them, could find a way to employ them. However, it doesn’t end there. The students in “normal” schools would come to know more of the difficulties, diversity and potential of humanity, and become better at living with and working with that diversity in their adult lives. Perhaps, in the future, they might be more inclined to employ a young autistic person. So, this proposal would enhance their education and make the world of the future better. If we don’t want our schools to do that, why are we in schools?

John Claughton is former chief master of King Edward’s School in Birmingham

This article originally appeared in the 22 February 2019 issue under the headline “How can children in special schools cross the divide?”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles