How to talk to your children about sex

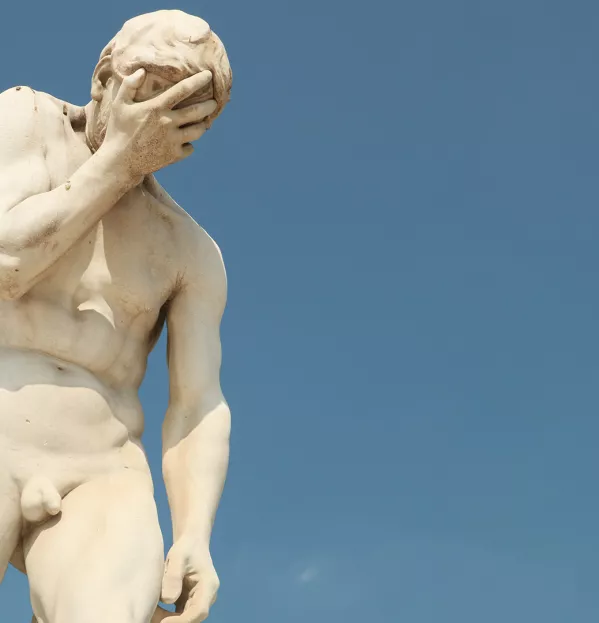

I have been avoiding writing this article since I was asked to do it. I have read an entire novel for my book club, I have caught up on emails, rearranged my desktop, cleaned my daughter’s bedroom and “thought” about avoiding writing this article a whole lot.

Maybe it’s my very Scottish embarrassment about the issue, perhaps it’s my Catholic upbringing, maybe it’s a generational thing - or, indeed, a combination of all three - but I can’t bring myself to begin. But what could be causing all this prevarication? Well, simply this: it’s about sex education.

Even the thought of it is bringing me out in a cold sweat. In my day (not all that long ago), personal and social education as we know it now, as a timetabled subject, simply didn’t exist. “The Talk” was for girls only, who were taken out of class to hear about menstruation, sanitary products and generally told to stay away from boys.

I don’t know what the boys left in the class were doing during this time but it couldn’t have been any more miserable than what we were sitting through. The only other education on the subject arrived during biology when section 6.6 of the book was arrived at and the long-suffering biology teacher stumbled through the pages covering the human reproductive system; a sigh of relief from all concerned was audible following that lesson.

Thankfully, we now have a much more thought-out, needs-based, age-appropriate curriculum offer in our classrooms. I know that some parents have concerns about some of the content, so I’m pleased that these days they have the option to speak to school staff about these worries.

I am absolutely not criticising parents - I’d be criticising myself - for being woefully underprepared and awkward when it comes to dealing with sex education. The world we live in now has changed in so many ways and attitudes have shifted significantly since we were on the learning end of the conversation and, while the birds and the bees element of PSE is still the same as ever, there is naturally a disconnect between the parent and the child, as we are not living their lives in today’s world.

There is a tendency to say that the old way of doing things was “good enough for me” or “didn’t hurt me” when, in actual fact, maybe it did. Maybe we would have been better prepared for relationships; maybe we would have been more comfortable in our equivalent of PSE if the adults teaching us had been more sympathetic, less black and white, less uncomfortable about the whole thing.

A-changing times (and acronyms)

We do our young people a disservice by keeping the subject hidden. I am regularly genuinely astonished at how my children and their friends handle issues of this nature. It’s not about sex to them, it’s not something to cover up and avoid all mention of: for them sexual attraction is part of their identity, part of their friends’ or classmates’ make-up. It’s just not so much of an issue as it once was.

And I am learning, through them, not to be so scared of the subject. I am, like many of my friends and probably lots of parents of my generation, refreshed and empowered by their attitudes, their honesty and their acceptance.

Our children live in a fast-moving, 24/7 world in which information is available at their fingertips whenever they want it. It’s a world where, at the behest of opaque algorithms, unhelpful information appears suddenly without young people seeking it out. Amid all this, it can be difficult to take time to be sympathetic, to be kind, to listen to anxieties.

Young people in 2020 live in a different world from teenage me. They have access to more information - for good or for bad - and we need to equip them to filter this for themselves. They need to be resilient and they need to know that what feels wrong to them probably is wrong.

One thing I know is that PSE, RSHP (relationships, sexual health and parenthood) - or whatever abbreviation or acronym it is known by - has to continue to meet the needs of our young people. The discussions from early primary about their body and their significant relationships is important not just to safeguard them from harm, but to develop an awareness of themselves. They need to know that they alone have the power to say who touches them or who they want to be intimate with; they have to be aware of other classmates or friends and be considerate of their feelings, too.

Ultimately, sex education needs to meet their needs - not mine. My embarrassment, my fumbling around the topic, my lack of understanding of what it’s like to be a teenager now is secondary to what they need to cope with their environment and to best prepare themselves for an adulthood with even more change, more social media, more airbrushed throwaway images and less tolerance. We need children to be secure in their own skin and be able to handle relationships with others.

If we can help them towards that, whatever missteps we make along the way, maybe they’ll understand - and not blame us too much - when they have to repeat the process with their own children…

Joanna Murphy is chair of the National Parent Forum of Scotland

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters