Make the robots play by your rules

How many of us enjoy being watched as we work? I remember well the fears and concerns that the introduction of classroom observations for performance-related pay unleashed a few years ago.

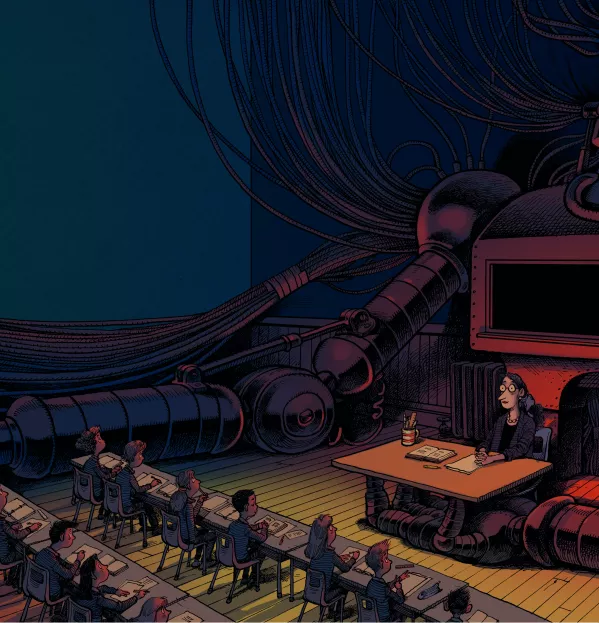

Imagine, then, a process where, instead of a colleague or your line manager coming into your lesson, there are cameras and a tiny microphone fixed to your classroom wall, picking up everything that is going on. And it may not be you, as the teacher, who is the key focus of the observation but the pupils.

At the end of the lesson, an artificial intelligence (AI) machine analyses pupils’ facial expressions: how many times they yawned, whether they looked happy or sad, and how well they were engaged in the task. All of this is intended to tell you more about your students’ learning and to make you, the teacher, better at your job; to point you to where you lesson was effective or to where it might have been lacking in spark.

It sounds outlandish and a little bit scary, doesn’t it? Such practices may well seem inconceivable - for now - in UK schools, but in China, such intrusion into everyday life in classrooms is already happening.

With its burgeoning population and competitive stance in global education performance rankings, China has invested heavily in educational technology in recent years. The AI system described above is called Edubrain and it is currently being trialled in several Chinese schools.

Edubrain employs facial recognition technology more commonly used for apprehending criminals or verifying payments. It looks to evaluate the “appropriateness” of students’ reactions as well as to interpret their learning progress from the data collected.

The use of such systems raises some important ethical questions about who is using AI technology in education, how and for what purpose. Teachers, learners and parents are entitled to ask how the data collected will be stored and what steps will be taken to protect the identities of those people whose comments and behaviour are captured by the technology.

AI can bring enormous benefits to teachers and learners when it is designed and used appropriately - even AI technology that uses facial recognition, if the purpose of the recognition is, for example, to identify students who are struggling and to offer them appropriate feedback and support. We must, however, also consider what the worst is that could happen if we do not effectively assure that AI used for education is ethically developed and used. So, what can we, as educators, do to reduce the risks?

Teachers have some difficult choices to make when considering the use of AI, but asking yourself these three simple questions will help: who is processing my data using AI and who regulates them? What educational need are they serving and how will I know if it benefits me, my family, my students? Who is developing the AI that is being used and how do I know they are causing no harm?

Indeed, concerns about the way that AI is, and will be, used in education are not restricted to a state-controlled country such as China. Our personal data and information are being disseminated, right now, in ways most of us have not yet grasped.

In recent weeks, it has emerged that some apps used on Android operating systems, including educational tools such as Duolingo, are feeding information to Facebook and other data-harvesting destinations without the permission of the person using the app. We do not know what that data is being used for and, even if we had been asked for our permission, without a real understanding of the implications of saying “yes”, we are in no position to give informed consent.

Those of us who work in education need to understand how AI works, what its many uses are - and let’s be clear that most will be highly beneficial to schools - and that our personal data and information is hugely valuable to those who would seek to abuse it, as well as to those who seek to use it to improve teaching and learning.

The pursuit of appy-ness

The example of Android apps feeding data to Facebook highlights another important aspect of the problems that we face as we try to ensure that our AI does no harm.

Just think about the number of hours that we spend with our smartphones: whether it’s Candy Crush, Instagram, Twitter or shopping that is your “drug of choice”, we have become heavily reliant on these devices for many reasons - not least because the applications they enable can be addictive and because they enable things to happen at speed. Want that takeaway ready for you when you get home? Just click the button. Need that pair of running shoes delivered to your door tomorrow? No problem. The immediate gratification that these devices bring can prevent us from taking time to think about the implications of actions. This can put us at risk.

As more and more companies move into the educational AI marketplace, we can expect to see parallel examples of Candy Crush and Twitter claiming educational benefits.

An addiction to learning might be a good thing, in moderation, of course. But how will we know if such educational infatuations are actually beneficial? Who will provide the due diligence on the companies and their products to check if their educational credentials are respectable? Who will ensure that the data they collect is used appropriately? And who will check that the content that is pushed out at speed is educationally valuable and free from hidden messaging and devious motivations?

Nor are the risks limited to the applications on our phones. With Google, Amazon, Apple and others all competing to be named the home assistant of choice at the Consumer Electronics show in Las Vegas last week, we must question the real implications of these voice-activated interfaces.

As these devices find their way into more and more homes and schools, what are their real benefits and what are the potential dangers? At the moment, the rhetoric is all about how these assistants can be used to entice people into making more purchases.

The aim seems to be to design devices that can be used anywhere in the home, the car and beyond. But what else might be going on here, as these companies start to further their land grab in education?

Once the initiative becomes about commercially developed voice-activated interfaces in the classroom, who should we trust to ensure that the conversations we hold with our software teaching and learning assistants are treated with respect and used only for valid educational benefits?

If neither a smartphone nor a voice-activated assistant is your cup of tea, then I would urge caution before you sit back and relax. These are merely two examples of technologies that use AI, and there are many more that illustrate exactly why we need to pay attention and act now.

Take YouTube, for example. It is, after all, the new form of TV, and TV’s educational credentials include BBC Bitesize and the medium’s fundamental role in the creation of institutions such as the Open University. YouTube’s terms and conditions require that users are aged 13 years and above, and yet billions of YouTube views come from children under 4. There is, of course, an app called YouTube kids that can ensure a more wholesome viewing experience, but it is not available globally in the same way as YouTube, and it accounts for just a tiny fraction of YouTube’s viewing figures.

Put simply, there is no current way of ensuring that young children do not consume completely inappropriate content. As companies such as YouTube adopt more AI tools to enable them to increase their customer base - perhaps through offering individually personalised viewing channels, for example - we really do need to find a way to help everyone stay safe.

Race to the Finnish line?

So, what can we do? The only way we can ensure that the transformative potential of high-quality AI used for education becomes a reality is by educating people about AI, so that they can help the regulators to keep them safe. We need everyone to understand why data is important to AI, how AI processes data to reach decisions, how AI is trained, what AI can’t do, when to challenge AI, when to worry about saying “yes” to the terms and conditions that we are asked to agree to when using some technology.

There are examples from which we can learn: Finland has introduced an initiative to teach 1 per cent of the country’s population the basics of AI technology. It will gradually build on the number who are taught, so that the population is empowered through education. Finland has recognised the clear economic incentive to staying competitive alongside AI superpowers China and the US.

Here in the UK, we have ideas of our own. The Educate programme at UCL, which I run, develops partnerships that support inter-stakeholder co-design to help educational technology developers, including those using AI, to better grasp teaching and learning processes, and to help educators and trainers to better understand AI and its application in education.

If we get ethical regulation wrong, we will face nothing short of a catastrophe - just pick your personal horror story and it’s probably possible with AI, big data and the credible veil of education. We must act now to prepare educators so that they, in turn, can help everyone to prosper in a future where they will need to be increasingly vigilant, if they are to benefit from the real power of AI.

Professor Rose Luckin is specialist adviser to the Commons Education Select Committee inquiry into the Fourth Industrial Revolution, co-founder of the Institute for Ethical AI in Education, and director of the Educate programme, based at the UCL Knowledge Lab

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters