Managing pupil behaviour is all in the eyebrow

I was 12 and sat next to Stevie B in the back row of Ms Cosby’s English class, a fact that represented immense opportunity. Stevie B was cool, or at least coolish, and I was surely not. But just maybe I could impress Stevie, appear a little bit dangerous.

There was an elastic band in my desk. I took it out and stretched it back, pointed it as if to shoot at a classmate the next row over.

At the front of the room, Ms Cosby was asking us questions about a short story, The Lady, or the Tiger? I think. I looked at Stevie and he looked at me, raised his eyebrows and nodded. Did I have the guts?

In this moment, I was similar to some student sitting in almost any classroom on any given day - an opportunist. Not a bad kid, potentially interested in the story under the right conditions, but influenced by a calculus of forces and incentives distinctive to the 12-year-old. Those incentives made me inclined to shoot.

And then, suddenly, almost imperceptibly, the balance of factors shifted. Ms Cosby, still talking about the story, subtly craned her neck as if to see more clearly what was going on between me and Stevie. In response, I glanced at my book briefly, as if searching the text, and then looked at her again. A classmate was talking about the story, but Ms Cosby’s eyes met mine briefly. She raised her eyebrows. She had seen me. I put the elastic band away.

The array of forces acting upon students are malleable, responsive to even subtle adult actions - especially to subtle actions. Merely knowing that Ms Cosby was watching me changed my behaviour. As one of my favourite books, Chip and Dan Heath’s Switch, reminds us, the size of the solution does not have to match the size of the problem. Very small actions can have prodigious effects on complex environments. So Ms Cosby’s moves in this interaction reveal a few very simple principles teachers can use to manage behaviour.

Use your radar

The first is that looking and noticing matter. I call these skills “radar” (seeing accurately) and “be seen looking” (making sure students know that their teacher looks and sees). If students know that we will see what they do - that we care what they do - they are far less likely to engage in the low-level behaviours that distract their peers and sometimes gather steam until they are not so low level. Taking a moment to look for follow-through - to be seen looking for follow-through - is one of the most powerful things a teacher can do and fortunately it only takes a second. Ms Cosby craned her neck just a bit, adding a bit of pantomime to make sure I could see she was looking. This changed my decision.

On the other hand, I recently watched a carefully planned science lesson go south. The teacher stood at the front and asked students to take their materials out, and immediately looked down at her lesson plan. If they did what she asked, she did not see it, and they quickly recognised this. Taking a fraction of a second to say “Please have your materials out on your desk in 10 seconds” and then scanning the room visibly - see I am looking, I know what you do and I care - might have saved her lesson.

Similarly, prevention beats cure. Ms Cosby stepped in early, before there was anything all that “wrong” to address. There were merely the antecedent rumblings, subtly but unapologetically addressed. Prevention and subtlety are related. The first hints of distraction can be fixed with a look, a gesture or even a quick general reminder: “Make sure you are taking notes and tracking your peers.” They allow you to fix things with the least invasive intervention. After the elastic band has flown, and there has been a loud, “Ow!”; after snickers by unknown but presumptive accomplices, the fix is necessarily bigger - much bigger. It will cause all students to be off task because, for a time, there will be no task but only you hectoring and lecturing and interrogating. Just possibly, calling attention to a student like the Young Lemov - “Mr Lemov did you shoot that?” - would have been just what I was looking for and an incentive to try again.

Elastic bands and spit balls and snide remarks compete, we should remember, with fractions and density and All Quiet on the Western Front. The teacher’s goal has to be not only to make the latter more interesting than the former, but to get students visibly busy at those things so their engagement is observable to those who wonder: elastic band or short story? The answer to this question lies in part on what the rest of the class is doing. If looking toward Stevie B, I had seen his head hunched down over his composition book and his pencil scratching away, the circuit would have broken early of its own accord. Culture beats behaviour every time, in short. But culture sometimes must be built intentionally, brick by brick.

So, yes, give students engaging activities full of real content and intellectual challenge. But as they are building a habit of industriousness, make sure their engagement is observable, so it is easy to manage and so it is more clearly visible to other students as the norm. Step one is to give observable directions. Saying “Track the speaker and have your pencil in your hand, so you can take notes during discussion” is a far better way to tell a student to pay attention than saying “pay attention”. If the student doesn’t follow through on the latter request and you say something like “I thought I asked you to pay attention”, he will invariably say “I was paying attention”, perhaps because he really thinks he was.

Either way, a request that cannot be verified by observation is very hard to enforce, and giving such directions over time risks building a culture marked by a lack of accountability. But a room full of students tracking the speaker sends a powerful disincentive to the one student most likely to disrupt.

Distract the audience

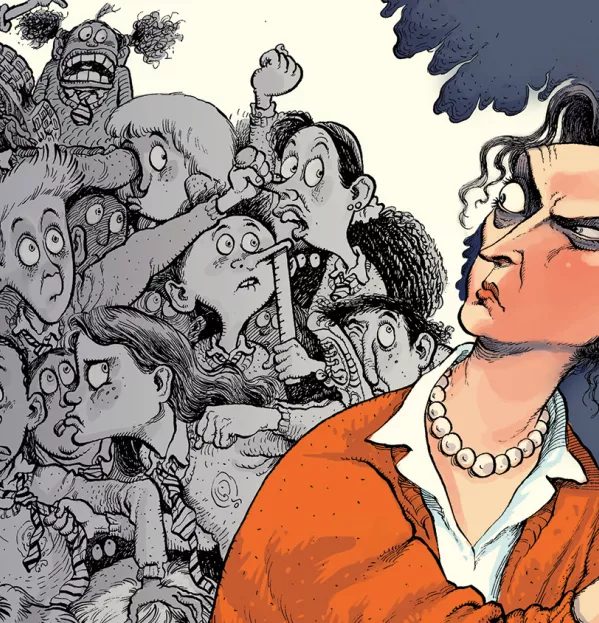

You are perhaps thinking now of Danny. He is your student most likely to disrupt. He is a disruption artist - wilful, crafty, intimidating. You are quite sure that none of this glancing artfully his way and giving observable directions is going to fix the likes of Danny. And there you are, in many ways, correct.

Danny is going to take work, tenacity, consistency on your part, not to mention a whole different set of tools. But here is one thing that is important to remember about Danny. He seeks control. He seeks admirers. He seeks converts. It is a lot more fun to be Danny with a guffawing chorus of acolytes. So, the first step is to win the middle, to take his potential chorus and engage them in productive activity. Danny takes a lot of work. But it is when Danny has started winning followers who cheer him on and copy his antics that the end game begins.

Two Dannys in your classroom is a game you can win. Twelve Dannys is the death knell for learning. So, no, these principles won’t solve that challenge overnight. But they can help limit his disruption and preserve your energy, so you can focus successfully on the toughest cases. Then you can aspire not only to teach Danny’s classmates; you can aspire to teach Danny.

This article appears in World Class: tackling the ten biggest challenges facing schools today, edited by David James and Ian Warwick; published by Routledge

Doug Lemov is the author of Teach Like a Champion and Reading Reconsidered: a practical guide to rigorous literacy. Find out more at teachlikeachampion.com

He tweets @Doug_Lemov

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles