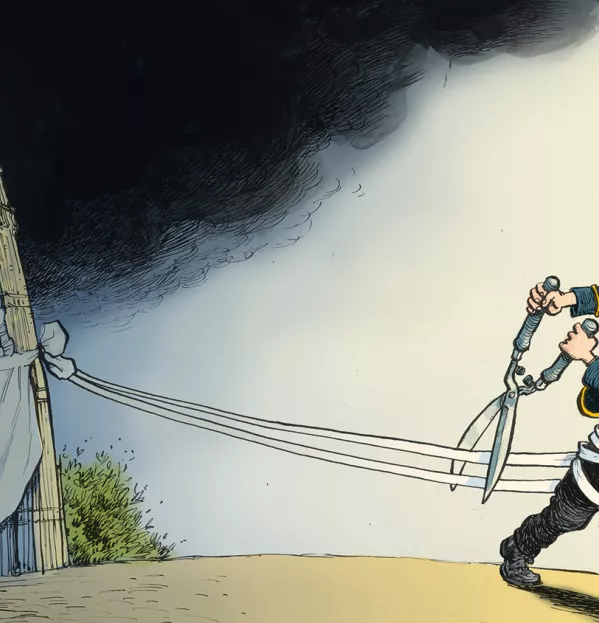

More autonomy turned out to be mere rhetoric

The Academies Act of 2010 purported to take school autonomy to a new level. The jury is still out on whether this could make a difference for pupil outcomes, but doubts have, justifiably, begun to emerge.

While there is evidence of a positive impact in pre-2010 sponsored academies, recent research from the London School of Economics finds no trace of post-conversion improvement in previously “good”, “satisfactory” or “inadequate” converters, as well as a concerning degree of heterogeneity.

Meanwhile, the reality seems to be dawning on headteachers that the new autonomy promised does not amount to much. Responses to the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) survey revealed a widespread perception that, when it comes to resourcing and curriculum decisions, there’s no real difference in the degree of autonomy between academies and maintained schools.

In a new report, Optimising Autonomy, published recently by the Centre for Education Economics, I consider what may lie behind these findings.

In 2010, the Conservatives brought to government far-reaching plans for education, involving supply-side reforms and significant changes to curriculum and qualifications. But while the political rhetoric emphasised academy freedoms, the emphasis of the legislation, and of academy funding agreements, shifted to underscore the conditional nature of schools’ autonomy, and the powers of intervention afforded the secretary of state in the event of things not going according to plan. The result has been that “autonomy reforms” have steadily given way to a more centralised and interventionist approach.

In consideration of present arrangements, the report says that the current accountability framework offers little reason to believe that significant innovation and improvement will ensue from the reforms undertaken since 2010.

Competition is blunted because success is overly determined by league tables and other accountability measures that focus on too narrow a range of subjects.

The government’s nationalising approach to curriculum and qualifications reform, while predicated on solid research on knowledge-led, traditional teaching methods, looks past other research on the effectiveness of some modern methods for developing reasoning skills, and the fact that we do not yet know what the balance of skills required in the future job market will be. Schools and parents have been largely excluded from having a say over the trade-offs involved in decisions about curriculum content and qualifications.

Unhealthy competition

Without parent choice to harness and discipline it, competition is prone to go awry, and even more likely to do so in the kind of certification and accountability regime that we currently have in England. GCSE scores cannot provide adequate data for assessing institutions - or national-level improvement - because the “comparable outcomes” approach taken by Ofqual to awarding effectively puts a cap on overall attainment.

This is why we need international assessments like Pisa and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss), and the National Reference Test, for benchmarking and corrective purposes, to help us detect the learning gains that GCSEs cannot.

As things stand, however, the pressure that accountability goals place on GCSE certification leaves teachers and heads demotivated and vulnerable to short-termism, gaming, and worse.

These problems are exacerbated by a poorly designed system of intervention that cannot be other than weak in relation to the potential for rent-seeking and cronyism. The essentially network-based nature of brokering, therefore, has negative consequences for competition. It also, and more profoundly, runs the risk of poor sponsor fit.

The report makes a number of recommendations for improvements. Changing our approach to general certification by resetting the national curriculum requirement to a minimum standard, leaving Ofsted to assess curriculum quality on the basis of what we know from evidence and introducing a US-style secondary school diploma to place greater emphasis on institutional quality would be a good starting place. Though safeguards would need to be in place (as in many US states), to guard against the inflationary effect of teacher assessment.

On this model, the role of GCSEs changes: students would in general probably take fewer of them, with a core of key subjects, but it would leave wider scope for exploration ofdifferent subjects and pathways, while allowing for the demonstration of some early specialism, too - to take further, or not, at A level.

At the same time, retention of national competency-based testing at 11 and its introduction at 16, should provide the data necessary for a separate value-added estimation exercise for accountability purposes. This could usefully augment Ofsted assessment validated with reference to what has been established in research.

In respect of the system of oversight predicated on these arrangements, there should be much more emphasis on parent accountability, choice and competition. This means:

* Implementing a national funding formula.

* Increasing the premium for disadvantaged pupils to attract the right new operators to areas of poor provision.

* Phasing out the use of additional funding streams and caps to control the growth of academy chains, so that effective innovators can scale.

Competition and reputation mechanisms should be supported further by allowance for full rationalisation at MAT level, directing funding to them, and giving them fuller resource autonomy. Greater parent accountability would be further facilitated by a voucher, open admissions, simplification of the admissions code via the introduction of lotteries for oversubscription, and investment in school transportation.

It is important to stress that none of this obviates the need for public accountability. It is right that schools should be held accountable for the way they use their resources, and for pupil outcomes. But accountability makes most sense when those being held accountable can actually make a difference to outcomes - through properly conducted experiments and informed response to judgements.

Unfortunately, the confused and conflicted nature of oversight has left leaders largely impotent in these and many other respects - a reality that carries potentially serious consequences with respect to the likelihood that autonomy reforms can ultimately prove successful.

Reform of school oversight should begin with a clear delineation of the responsibilities of the various agencies involved. At a basic level, the national schools commissioner (NSC) has responsibility for anticipating need, shaping future provision and managing takeovers where intervention is required. Ofsted’s job is to monitor and inspect standards in schools.

This being the case, it is Ofsted that should be supplying the justification for regional school commissioner (RSC) intervention, not the Department for Education.

Where this is given, an open tendering framework should decide which sponsors/MATs, and/or other kinds of providers, should take over the school in question. If the NSC and his deputies were to make independent appointments, we could achieve both greater transparency and more effective competition between providers than under the present brokering system.

Importantly, the scope of these briefs is such that neither the Education Funding Agency nor local authorities need be involved in oversight: their responsibilities in this regard would pass naturally to Ofsted. There is a strong case for removing to RSCs the statutory basis of LA involvement in place-planning and school improvement as well.

Overall, the current system is not one that can produce transformational change. Among academy leaders, those supposedly in the vanguard of reform, there is a growing feeling that - if at any time it was - it is no longer justifiable that more should be expected of them than others. And there is little point in maintaining the apparatus in its current state of repair.

But that is not an argument for abandoning what we have started. Instead, we must invest in optimising autonomy by resetting and better supporting reforms already in train.

James Croft is the executive director of the Centre for Education Economics and author of the report Optimising Autonomy: a blueprint for education reform

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters