One small change could make a big difference to MATs

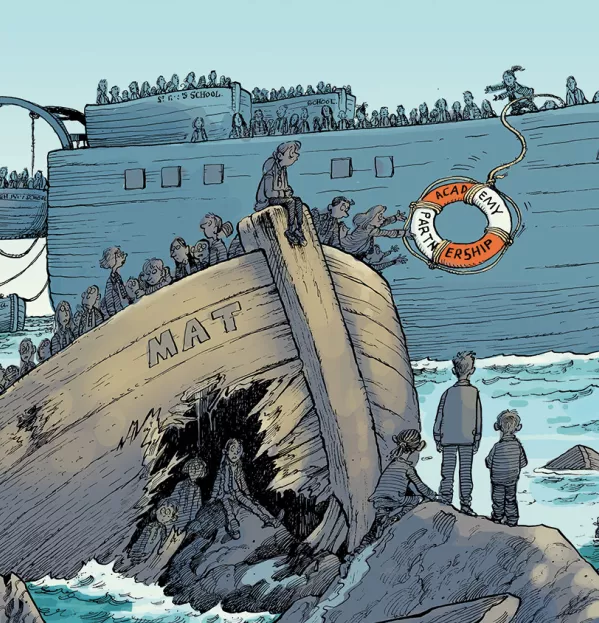

Few will have been surprised to see schools that are part of a multi-academy trust (MAT) near both the top and bottom of the latest league tables.

The best academy chains contribute positively to school improvement, and some sponsors are skilled at securing rapid gains in previously underperforming schools by deploying experienced staff from elsewhere in their group. On the other hand, the failures and financial irregularities of many academy trusts are enough to make those of us working with them blush.

The frequency and scale of these problems point to structural difficulties with the way MATs are set up that makes them vulnerable to financial mismanagement and failure, the consequences of which are damaging for schools and communities.

Logistical challenges

Yet, despite this backdrop, academy policy appears to have reached a stalemate. The government’s 2016 plans to force every school to become an academy feel like ancient history. But a move in the opposite direction, with all schools moving back to the ambit of (much withered) local authorities, would be logistically challenging - and strongly opposed by those who have seen their local schools improve in the 15 years since the academies policy was introduced.

Sir David Carter’s announcement before Christmas that schools could now join MATs on an “associate basis” suggests a willingness at the Department for Education to look again at how academy arrangements operate. We need to build on the successes of the academies policy while addressing the system’s current weaknesses, including delays in securing support for the schools that need it most, and the tendency for academisation to reduce, rather than increase, the scope for schools to take their own decisions.

I believe one straightforward change could transform the relationship between MATs and individual schools: we should abandon the notion - which clearly does not always work in practice - that schools join MATs on a permanent basis. Instead, schools needing support should be matched with an “academy partner” (the change of terminology is important) on a fixed-term basis of, say, five years. At the end of this period, both the school and the academy partner would decide whether they wished to enter into a new agreement for a further five years. Schools already in a MAT should also move onto five-year fixed-term contracts.

Legal status

Schools working with academy partners that, like the best MATs, provide well-targeted school-improvement support, facilitate excellent CPD opportunities that support staff recruitment and retention, and offer cost-effective and efficient back-office services, would generally opt to stay put. But schools working with less-effective organisations would be able to seek a new partner. Such an approach would also give the academy partners themselves the chance to develop in a more structured way, for example, by choosing to work only with schools in a defined geographical area or in a particular phase.

Why call these new organisations “academy partners” rather than MATs? As those with a good grasp of how MATs are legally structured will understand, at present, when a school joins a MAT, the school ceases to become a separate legal entity. So the MAT is not really the sponsor of a school in any commonly understood sense of the word; rather, the school becomes a branch of the MAT itself, along with all the other schools in the group. The new terminology would demonstrate a separation between the organisation supporting the schools and the individual schools themselves. To introduce such a change, schools’ full governing-body powers would need to be restored.

These changes would particularly benefit the growing number of schools - community schools deemed inadequate by the regulator Ofsted, and academies whose MAT has failed - that are unable to find a MAT that will take them. The current set-up forces the MAT to take on full financial responsibility for the schools they work with, which makes a school with an adverse PFI arrangement, or buildings in dire need of repair, an unattractive prospect.

When MATs refuse to take these schools on, they are not acting selfishly - they are following their charitable objects, which require them to put the interests of pupils already in the trust first. A new fixed-term arrangement, with school and academy partner remaining as separate legal entities, would enable the academy partner to provide school improvement and other support to schools in this position, but with none of the financial risk; this would make it easier to find partners for struggling schools in a timely manner.

Temporary arrangement

Nor would this be a soft option for underperforming schools. In certain clearly defined circumstances, the academy partner would be empowered to appoint additional governors or withdraw delegated decision-making to ensure necessary changes were implemented. But, unlike the current MAT model, the removal of decision-making would be for a short period while the school’s difficulties were addressed, rather than being a permanent arrangement.

The new set-up would also increase the number of academy partners available to provide support. The much-reduced risk and financial implications would mean that many more high-performing schools and teaching-school alliances would likely be willing to take on the academy partner role than have become MAT sponsors. In many cases, working in this way would formalise and strengthen existing informal school-to-school partnerships. Equally, the range of locally based school-improvement partnerships that exist up and down the country, some grown from local authority advisory services, others with roots in the old education action zones, could also be designated as academy partners working with groups of schools.

In practice, one might expect only a minority of schools to choose to seek a new academy partner after five years. But creating fixed-term rather than permanent relationships would change the dynamic for all schools working as part of a MAT. This arrangement would take us closer to a truly school-led system, making it more likely that struggling schools would receive support and intervention without delay.

Alison Critchley is chief executive of RSA Academies. She tweets @Ali_Critchley

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters