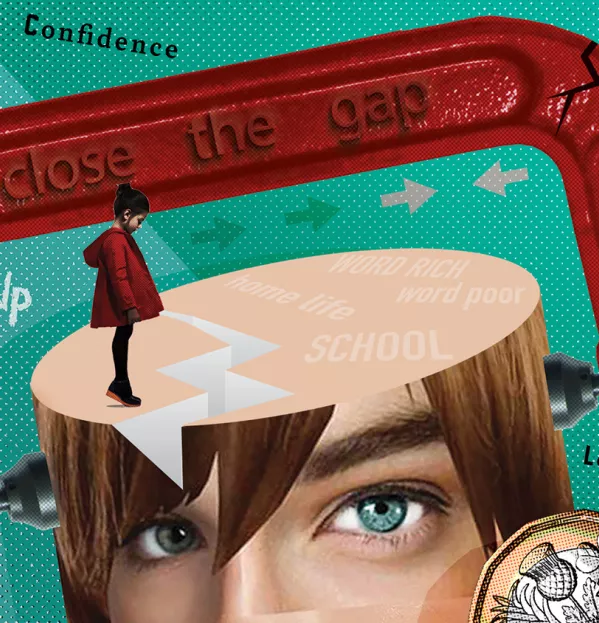

Close the gap: that’s our mission. Close the gap between the weakest and strongest; the richest and the poorest; the exceeding and the emerging. Close the gap between home life and school; between the cultured and the uncultured; the word-rich and the word-poor.

But any teacher with their sights set on a completely gap-free class is doomed to failure. Gaps are tricky things to close: as soon as one side starts to catch up, the other moves effortlessly away, and when the void is less gap and more chasm, it’s hard to show any narrowing at all.

Of course, closing the gap isn’t something you’re expected to do all on your own. There is backup in place, in the form of funding.

Often, what is just as important as actually closing the gap is that you are seen to be closing the gap. Huge swathes of time are devoted to detailing things you are putting in place to help any child who qualifies for financial assistance.

While this can be a useful exercise, it does run the risk of becoming one of those activities in which the improvement that has been made to a child’s education on paper far outstrips the reality.

Pupil-premium money is a case in point. As a class teacher, you will probably get a big say over where it goes. Like I did with Tiana. She was in our class a few years ago, accompanied by extra funding. As her teachers, we had the last word on how the money should be spent, but, crucially, myriad ways in which to spend it. We arranged for Tiana to have weekly one-to-one tutoring; we paid for her to learn the violin; she took part in a nurture group; and we made sure all trips were heavily subsidised. All of these things not only helped her on paper, but also in reality. They widened her experiences; helped her social and academic development; and boosted her confidence and happiness.

Limited resources for extra support

I was reminded of Tiana the other day when I was thinking about how we are using the funding for Holly. In many respects, Holly and Tiana have similar needs. They are both from fairly chaotic homes with little money or support. They both have gaps in their learning and social skills. They both need extra attention and an injection of self-esteem. Like Tiana, we, as class teachers, were asked to note and evaluate the effect of the spending because of the need for “evidence”.

“I can’t really do this,” I said, after nearly an hour of staring at a blank form. I wanted to give Holly extra pastoral care. I wanted to give her after-school clubs and extra support in the classroom; some one-to-one time. But I couldn’t.

I had the same amount of money, I was the same teacher, but, unlike with Tiana, I was shopping from empty shelves. There were no nurture groups, no spare staff to offer pastoral care or support in class. She couldn’t take part in after-school activities because her mum didn’t drive and insisted she get the school bus home. Aside for subsidising trips, I was struggling to see what we could do.

Ironically, attending a school in a more affluent area was probably the very thing that had narrowed Holly’s support options. It was another gap that needed closing. In this case, I couldn’t help thinking we’d have been better off converting the money into book tokens and taking her shopping.

Jo Brighouse is a pseudonym of a primary school teacher in the West Midlands. She tweets @jo_brighouse