I looked in horror at the iPad as the audio was cut off mid-sentence. This couldn’t be happening! It was The Archers’ hour-long trial special and the jury were about to return a verdict. Even Mr Brighouse (who has been known to comment that listening to The Archers must be what being dead is like) was showing a vague interest in the outcome. The suspense had been building and building and now, at this crucial point, I was being denied narrative closure thanks to a dodgy wi-fi connection.

As a teacher, you should never underestimate the power of stories. Whether it’s playground gossip or the life of Henry VIII, our need to know what happened next is hardwired. I used to spend hours planning “wow factor” lessons and assemblies, collecting props, music and computer effects to try to sustain children’s attention when all I actually needed to do was read them a story.

The trouble with extracts

Extracts don’t have nearly the same impact. When I was a newly qualified teacher, the restrictive timings of the literacy hour often forced teachers to use text extracts and save whole-class novels for story time at the end of the day. The rise of guided reading (with the dreaded daily carousel activities) allowed children to read whole books but often at a snail’s pace. And while top readers were getting stuck into Michael Morpurgo, some children ventured no farther into language than Biff and Chip’s magic key would allow them to go.

Getting children to study a text that is beyond their reading ability should be a no-brainer. We do it with young children all the time. My preschooler has no idea what the black marks on the page mean, but he can recite The Gruffalo pretty much verbatim.

And it makes teaching so much more fun. Sharing a book can transform your classroom. Their delight in the gruesome descriptions of The Twits; the collective gasp when they realise what Bess has done to save the Highwayman; the palpable relief when Aslan comes roaring back to life. The premise is simple: take one great book by one great writer and read the hell out of it. Don’t kill it stone dead by getting everyone to read a bit out loud: read it to them. Call on your most confident readers for help and throw in a bit of whole-class choral reading to mix it up.

Ultimate textbooks

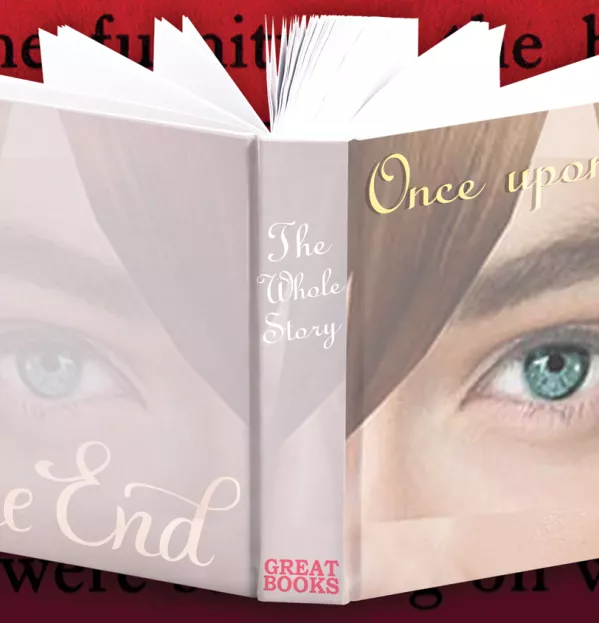

Great children’s books are the ultimate textbooks. Everything you need for a good English lesson is here: vocabulary, grammar, characterisation, comprehension and inspiration for writing.

Beg, steal or borrow to ensure every pupil has their own copy of the book (nothing kills a great read like sharing it with a fidgety classmate). And when your children write their own stories, don’t even consider commenting on grammar or spelling until they’ve had a chance to read you the whole thing - however flawed and zombie-filled the plot.

Put simply, if you want to be a good primary teacher, you can’t do it without some good books. End of story.

Jo Brighouse is a primary school teacher in the Midlands