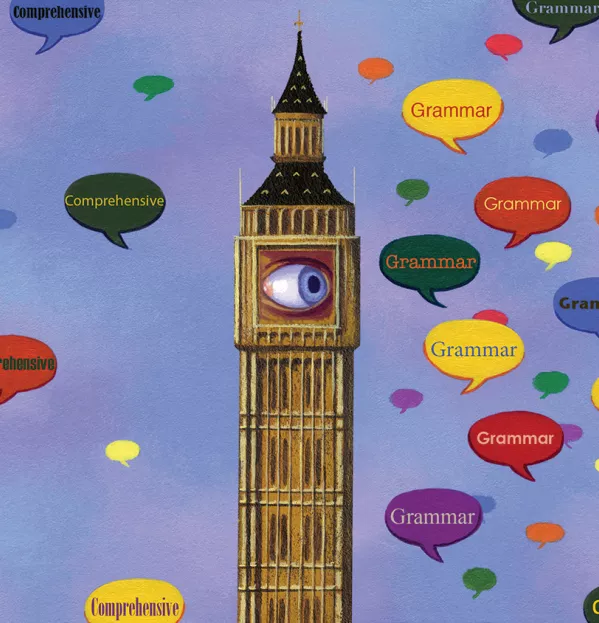

Parent power rules in the rise of grammar schools

As the wind dies down after a rash of teacher union conferences, I’d like to exploit the calm before the media storm that will inevitably accompany the final few days of this particularly sanguine general election.

If there is one near-consensus coming out of arguments in the educational press about the re-introduction of grammar schools by the Conservatives, it is that this is a political decision, not an educational one.

What good does that do? Well, it gives us a rare opportunity to spell out the difference.

No-one should be surprised that reintroducing grammar schools generates so much anger. It forces teachers to confront the purpose of their job and where they sit in the food chain. If you’re a fireman, policeman or nurse, you protect and save lives. You’re acutely aware that yours is an admirable, selfless, quintessentially decent calling. You are at the mercy of the politicians’ budget, so you argue with them about it. You hope and pray enough of them possess the decency to support you.

If you teach in a state school, your position is similar but not the same. Some are comfortable with their place in the food chain: others resent, reject or rise above it. Rising above it usually means seeing your role as far more complex and significant than any strategy created by civil servants in the thin window of opportunity between education ministers.

That harsh, binary choice between comprehensive and grammar schools, selection and non-selection, has always been a political battle. Selection, for a host of reasons to do with how children behave, is educational common sense. It’s why a teacher selects one child to sit with another, or separates them. It’s why they select and encourage some older children to support or mentor younger ones, or organise events or movement around a school to split age groups. It’s why teachers are wise to nurture some friendships and discourage others. Selection is an essential part of the job.

The comprehensive ideal has nothing to do with educational practice and everything to do with politics. It was always about an ideological pursuit of fairness: levelling the playing field instead of nurturing the confidence to compete on it. Its shelf life was limited by the political climate that manufactured it.

Step away from the history and think about today, and what becomes clear is that the political strategy behind re-introducing grammar schools has far more to do with votes than education. Grammar schools are undoubtedly popular with parents, and there are even more parents than there are teachers. I’m hardly the first to spot this, but I think understanding why they are popular with parents throws some challenging light on the issue.

Parents aren’t interested in what researchers, statisticians, educational lobbyists, thinktanks, union leaders or teachers say about grammar schools. It’s their perception of them that matters: a deep-rooted, dominant one that crosses cultural and age boundaries.

Appearances are everything

From this perspective, grammar schools represent educational standards to challenge even the elite boarding schools. Parents believe they teach an attractive range of subjects to a standard high enough to launch children on a secure path to adulthood and successful careers.

They may not have the facilities, scholarly staff or reputations of the elite fee-paying schools, but parents feel they are far more interested in excellence than equity, individual success than collaboration. And no parent thinks their son or daughter is average.

In contrast, comprehensive schools are seen as being more about society than the individual; equity and social change more than educational success. I would even argue that there is something fundamentally adolescent about the comprehensive school which mimics deficiencies in other aspects of contemporary culture. A culture that thinks more adults reading children’s books is good news has a maturity problem no less critical than a political party that believes a 67-year-old student activist can lead the country.

This uncomfortable conflict of aims is present at the highest level. It’s there in the Department for Education’s current vision, which states: “Our goal is to provide world-class education and care that allows every child and young person to reach his or her potential, regardless of background.”

We are obsessed with pursuing the after-thought from this vision, at the expense of the goal of world-class education. We lack world-class schools because so many of the influential players, organisations and individuals are only interested in social mobility and politics.

When Tony Blair said, “Education, education, education,” what he really meant was “Social engineering, social engineering, social engineering.” As any good teacher could have told him at the time, “It’s metonymy, stupid.”

Parents who will bother to vote in June are neither stupid nor bigots. And their perception of schools really matters.

Joe Nutt is an educational consultant and author

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters