In the early years of the new millennium, a new educational breed came to the fore: the hero headteacher. Charismatic, extrovert, decisive and unrelenting on standards, he (and it was more often than not a “he”) led his school with an iron will, taking no prisoners.

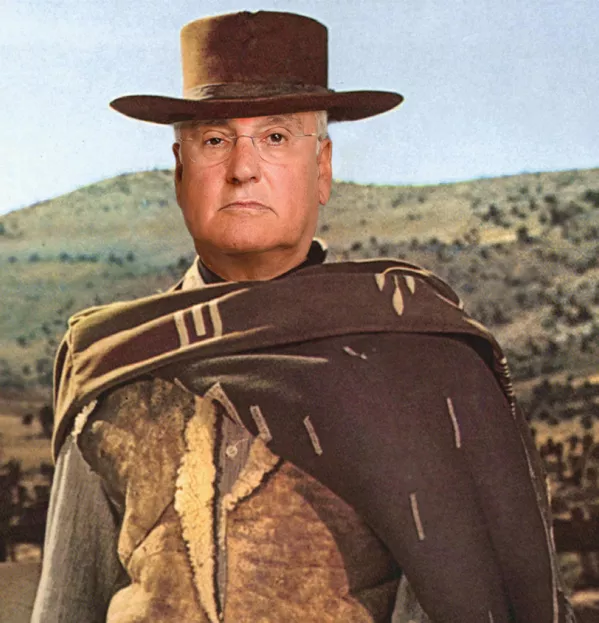

And no one epitomised this phenomenon more than Sir Michael Wilshaw, the Clint Eastwood-styled swaggerer of Mossbourne. He’s been lauded by politicians and resented by many teachers for his many confident pronouncements over the years and it’s one of the many reasons why “Wilshaw (proper noun, profanity)” - as in, “You’re talking absolute Wilshaw!” - still manages to make teacher Mark Roberts’ list of the top 10 teaching words of 2020. (Although, it has to be said, Sir Michael has since earned some grudging respect by going back into the classroom at the age of 74 to help out in these Covid times.)

It’s not hard to see why heroism in leadership is so attractive. It denotes strength, nobility of character and courage. On the face of it, great characteristics. But it all depends on how you define and live them.

When heading up any organisation, it’s very easy for the power to go to one’s head. You’ve climbed your way up there to the top; you’re brilliant - because everyone tells you so. People are looking to you for direction, for answers, for inspiration.

Or so you think. Mostly, they are looking to you to keep the ship steady so they can get on with doing their jobs in peace and without distractions. They don’t want regular reminders of how wonderful you are. What they want is to be supported, nurtured and encouraged.

And they don’t want constant displays of heroic behaviour. If someone is struggling, the temptation may be to slap on those red big-boy or big-girl pants and swoop in to save the day. Of course, no one can do things as well as you can - after all, that’s how you got to where you are today.

But what leaders often forget is that they got to where they are because someone patient and wise helped them to get there, by letting them try and fail, by holding their hand through the wobbles, picking them up when they fell and helping them to see what they did wrong. And, most important of all, they trusted them to carry on doing their job.

When a problem occurs, it may look like the best solution is to fix it yourself or give it to someone you know can fix it; it’s certainly quicker. But who really benefits in that situation? Taking the problem away may ultimately cause more harm than good, says Adam Riches, an assistant principal and senior leader for teaching and learning. It de-skills the person in question and adds to your or someone else’s workload.

Good leadership means not subscribing to a “do-it-myself” methodology but instead promoting a “do-it-yourself” style. It means helping others to succeed. It requires you to feel secure in your abilities and in your position. It needs you to coach and to nurture people so that they become capable of taking over from you and to have the confidence not to feel threatened by that. It requires time, patience and generosity of spirit. Most of all, it requires trust. Trusting yourself is easy. Trusting someone else is much harder, but, in the end, so much more satisfying.

The best leadership does not need to be macho or heroic, as female leaders around the world have demonstrated recently. They’ve shown us that caring about others is not weak, gentle can be strong and that empathy is empowering. They’ve shown us that it’s less about “lean in” and more about “lean on me”.

Yes, courage calls to courage everywhere. But sometimes it does it softly. We just need to listen and learn.

@AnnMroz

This article originally appeared in the 4 December 2020 issue under the headline “Good leaders trust their staff - even if it means letting them fail”