On the school trip

“Every teacher has a great trip story,” says Rebecca Foster, head of English and associate senior leader at St Edmund’s Girls’ School.

Obviously, not all of those stories will be happy ones - in fact, some will be not so much joyous tales of bonding as nightmares about lost children and broken priceless museum exhibits.

So, how do you ensure that your school trip is more the former than the latter? If you have chapters one and two under your belt, all you need to do is put the plans in place and sit back while the excursion goes smoothly, right?

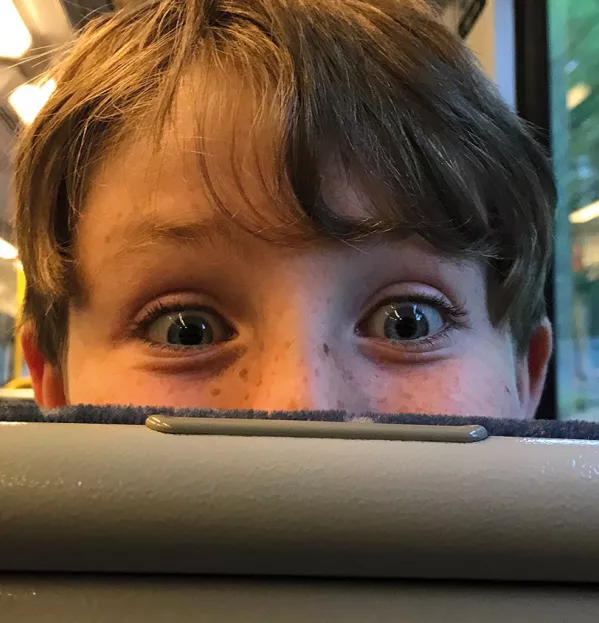

Transport

The first challenge is transport. Handling a group of excitable children in an enclosed environment such as a minibus or coach is not without its ups and downs.

So what coping strategies do teachers employ to ensure that journeys outside of school pass without incident? “Book a bus with a DVD player,” says Chris Wain, executive headteacher at Pallister Park Primary School in Middlesbrough. “If it’s a long journey, we’ll put a DVD on to keep them entertained.”

Running with the entertainment theme, Nina Elliott, curriculum leader for modern languages at Tor Bridge High School in Plymouth, suggests that, for older students in particular, it’s a good idea to let them choose the DVDs rather than the teachers (as long as the content is appropriate) - that way, they are more likely to stay engaged.

She also notes that, on longer journeys, a lot of children will be happy simply to plug in to their personal electronic equipment and be left to their own devices, although she makes a point of insisting on “no wi-fi hours” as a way of ensuring a degree of social interaction.

Teachers are generally in agreement that a “no food on the coach” policy is effective, and most coach companies now include this as part of their own conditions.

Food and toilet breaks

Kevin O’Brien, assistant head and Year 6 teacher at a primary school in Merseyside, says it’s important to schedule stop-off breaks to allow for snacks and lunch, as well as ensuring that water is available.

Colin Grierson, educational visits leader at Parson Street Primary School in Bristol, adds that, for longer journeys, the location and time of any food stops should be stated in the risk assessment.

Most teachers report few behavioural problems during transportation but much of this is down to effective forward planning.

For younger groups, especially, it is important to establish clear guidelines in advance and enforce them on the day, particularly when using public transport.

Take train travel, for which Sue Harte, headteacher at John Stainer School in Lewisham, has the following advice: “Make the expectation to the children very clear that there is no rushing on to the train: ‘If you’re just arriving on to the platform and the train arrives, you don’t get on unless the leader tells you’.

“Line them up along the platform so you can look along the line and see that everyone is getting on together. And then ensure you do frequent count-ups.”

Don’t assume, because your school is in an urban location, that pupils will have experience of all types of public transport.

“Interestingly, many of our pupils who live in London don’t use the Tube,” says Alex Yates, headteacher at the Royal Free Hospital Children’s School in London. “Partly that’s due to money because they have to pay to use it but part of it is due to anxiety.”

It’s all about challenges

Despite this, Yates says it’s important to look beyond such issues since to not use the Tube in London can be limiting.

“The travel is part of the development process,” he says. “It’s all about challenges and giving them experiences they can utilise in the future.”

For overseas trips, the journey itself takes on greater significance as part of the overall experience. On a ferry crossing, for example, the sensory experience can be quite exhilarating, especially for younger children. In such circumstances, a balance needs to be struck between the safety of the group and giving children the freedom to enjoy themselves.

Rae Snape, headteacher of The Spinney Primary School in Cambridge, says that on previous crossings to the Isle of Wight, her pupils have been allowed on deck but are told they must hold on to the side of the boat at all times. “It’s about managing that exploration in a sensible way,” she says. “It’s about the children having the sensation of the wind blowing through their hair and hearing the crashing waves but also the sensibility of what’s going to keep them safe. That is where your common-sense practice as an educator comes in.”

Foster adds that it’s important to set really clear expectations of behaviour on transport, including guidance on where the students can and can’t go, what they can and can’t do, and what the consequences will be if they misbehave.

“Generally speaking, if students know what the expectations are and what the consequences are then they’ll behave,” she says. “Be sure to follow through if students misbehave, though!”

Another thing to watch out for on journeys is signs of sickness. “We’ll ask about any sickness issues in advance but they can still happen because some pupils have never been on a ferry before, so they don’t know that they’ll get seasick,” says Elliott.

“It’s about knowing who those pupils are that are new to this and checking in with them regularly, and the staff as well, because if staff are seasick, it knocks them out for the whole journey.”

The quicker you can catch motion sickness, the better, adds Foster. After all “there’s nothing worse than being stuck on a coach with sick everywhere”.

Autonomy versus safeguarding

Striking the right balance between giving students independence, where appropriate, and making sure that they are safe is critical, not just when getting to the trip destination but also once you’ve arrived. “That freedom and autonomy is really important,” says Christian Pountain, head of RE and director of spirituality at a secondary school in Lancashire. “The trip is a great way of giving them the opportunity to blossom and mature in a really practical way that they otherwise might not get, but they need to do so within safe boundaries.”

Pountain gives one example of the type of trip that may lend itself to giving students greater autonomy.

“When we take a group to say, Alton Towers, as a reward for their hard work, they’re fenced in within the park, so once they are in there, they are free to go where they want, when they want,” he says.

“We don’t micromanage their movements within the park but we have guidelines on the number of times we meet up throughout the day and an agreed meeting point that we decide beforehand.”

Teachers are in agreement that wrapping the children in cotton wool on a school trip is neither practical nor good for their personal development.

Snape reveals that The Spinney Primary School has recently put into the school development plan an aim to introduce riskier activities, such as kayaking and wall climbing, because they help develop resilience and other competencies.

At the same time, she stresses that the school has a duty of care that it takes extremely seriously.

“One of the ways we mitigate risk is for teachers to think through in advance what the day is going to look like and visualise what’s going to happen.

“We have a very good culture around having a protective ethos.”

In a similar vein, Wain says that it’s important to give children the opportunity to take part in activities that are exciting and challenging but with the right focus on supervision and guidance. “I would look at it through the eyes of a parent,” she says. “If it’s OK for my child then it’s OK. You’re responsible for somebody’s child so you have to make sure that child is safe.”

Personal development

For Yates in particular, whose work at the Royal Free Hospital Children’s School brings him into contact with vulnerable children, being prepared to challenge those in his care can be important for their personal development.

“There are such low levels of resilience that they need confronting with difficult experiences in order to learn about themselves and what they can and can’t do, and what they need to work on next. That’s why the outside world plays a key role.”

It’s easy to assume that children who have a track record of behavioural problems are the ones whose independence you may need to curtail the most. Several teachers, however, report that this is not reflective of their own experiences.

“It’s often the children who you’re not thinking about as having behavioural issues that cause you the most difficulty,” says Yates. “You need to factor in that they may never have been away before, they’ve never travelled or been on a plane.

“They’re not just an amorphous group; you’ve got to think about all these details. In that respect, you rely on your staff and your form tutors.”

Location, group size and weather conditions are all variables that affect the balance of independence versus containment. Age is another obvious factor.

“Students can experience some independence at any age but how long you allow them to be on their own and in what conditions depends entirely on the age group and where you are,” says Foster.

“For example, if you’re with sixth-formers in France for a battlefields [trip], then you will allow them greater freedom in the evening than you would if you were on a trip with Year 7s, who would not be allowed out unsupervised in the evening.”

Controlled environment

Harte echoes the point about the need for younger children to be in as controlled an environment as possible. “We go to a residential centre [for an outward bound trip], which is very well set up,” she says. “We know exactly where our dormitories are and whether anyone else has access to the corridors. We take additional staff on those trips so there is always somebody with the children.

“The children know where the staffrooms are in relation to their dormitories. We don’t allow our children to run around freely on the site at all because you don’t know the other schools and other staff.”

Ultimately, Pountain believes that a one-size-fits-all approach to autonomy is rarely appropriate and the degree of independence afforded to students will depend on the make-up of the group. “You might trust certain younger groups more than certain older groups - it’s about knowing the kids.”

Trip attire

Whether to have a trip marker is another question subject to all kinds of variables. Again, age is a consideration. “For younger children, we have wristbands with phone numbers on, although we’ve not really needed them,” says Snape.

John Stainer School provides high-visibility jackets for the children with the school phone number printed on the back alongside a note that says “If I’ve behaved well, please tell my teacher”.

Harte reports that the adults also wear high-visibility jackets so they can be easily seen by the children. Other popular markers include coloured caps and T-shirts.

Wain, for instance, tells of taking a group to the London Olympics wearing T-shirts with “Olympics 2012” printed on so that they were easy to spot.

One potential downside, however, is that when children are poorly behaved, markers identify them as belonging to a certain school. For older children, teachers agree that markers are rarely appropriate since they are likely to cause embarrassment and resentment.

However, the question then arises of whether or not to insist on school uniform. Once again, context is key.

“For a reward trip, like the one we took to Alton Towers on a weekend, that reward would have been cancelled out a bit if they had been required to wear their uniforms, so we let them dress within reason in their own clothes,” says Pountain.

“During school time, kids are much more amenable to uniform being an expectation of them on an educational trip.”

Grierson also warns that a change of attire can sometimes mean that standards drop. “When children dress as they please, they behave differently to when they are wearing the school uniform,” he says.

Lost, sick or bad behaviour

School trips can cause changes in behaviour, result in medical issues, and see romances blossom and fracture. So how can you deal with these issues away from home in a public place?

Ski trips are a fixture on the calendar of many schools but they are also among the riskiest types of excursion, with visits to hospital and broken bones not uncommon. Pountain says that, under such circumstances, the priority is to release staff resources to look after the injured child while keeping things as normal as possible for the rest of the group.

“In those situations, we would have a member of staff that we’d allocate to look after that child and to stay with them in the hospital. For more serious injuries, then getting the parents out would be a priority,” he explains.

One of the scenarios most feared by any teacher is the moment you do a headcount and realise you are one child short. Your immediate priority is obviously to get the missing child back, says Pountain.

“You keep the kids where they are and ensure they are properly supervised and then put all your remaining staff resources into finding the child and establishing where they were last seen. Until you find them, everything else has to go on hold.”

Foster stresses the need to remain calm if a child becomes lost and to also be measured in your response. “There are clear protocols if a student gets lost, and it’s important to follow these carefully and not panic,” she says.

High emotions

School trips can elicit a range of emotions in children, from excitement and anticipation to anxiety and fear. Wain says the staff’s knowledge of the children is key to dealing effectively with such heightened emotions. “Every child will have somebody who’s their special person who they relate best to. That person would be there on the visit for reassurance.”

If, for whatever reason, a child is not sleeping or is distressed, Wain says that staff back at school would remain on call-out 24 hours a day in case the child needs to leave the group. “It takes the pressure off because they know that if something’s happened, whether it was an incident or an accident or just a child being distressed, we’d come out and take them home.”

On the reverse side of the coin, excitement can sometimes spill over into misbehaviour, at which point teachers are in agreement that it’s important to put down an early marker that such behaviour will not be tolerated.

“When we’ve had incidences of pupils being late back for a meet-up or they’ve been caught doing something they shouldn’t be doing, we have a “Velcro” policy, where they will have to sit beside me for the whole of that day or walk beside me,” says Elliott. “I tend to do that quite early with somebody, even if it’s just for half an hour, to put a red flag up right away as to what happens if you are misbehaving, because it’s the worst thing ever to have to hang around with a teacher on a trip.”

Among secondary students, in particular, it’s common for romances either to form or become public during a longer trip (Grierson notes that although romances are not allowed at primary age, that’s not to say they don’t occur).

Elliott says that, as a teacher, you have to be aware of such matters, particularly when you’re staying in overnight accommodation. “I’ve taken sixth-formers away and I know they are in a relationship but, regardless, at 10pm, the girls go back to the girls’ dormitories and the boys go back to the boys’ dormitories. I knock on the door and check. You have to be extra cautious and think back to yourself as a teenager and what you tried to get away with, and do everything you can to mitigate against that happening.”

Missing home

One of the most common issues with extended trips is homesickness and tackling the issue can be tricky. US academics Christopher Thurber and Edward Walton have written extensively on the subject. They define homesickness as “the distress and functional impairment caused by an actual or anticipated separation from home and attachment objects such as parents [...], characterised by acute longing and preoccupying thoughts of home”.

Almost all children, adolescents and adults experience some degree of homesickness when they are apart from familiar people and environments, with more acute sufferers typically reporting a combination of depressive and anxious symptoms, withdrawn behaviour and difficulty focusing on topics unrelated to home.

It’s important for teachers to be able to recognise the signs of homesickness, which Foster says can include students withdrawing into themselves, looking upset and possibly tearful.

Even better is to try to prevent homesickness occurring in the first place. Teachers say they do this by minimising contact with home, since many believe that the root of the child’s anxiety can be parents who are constantly asking after their welfare.

Harte says John Stainer School does not allow parents to contact their child while they are away “because it makes them much worse” and notes that parents can contact staff in the case of an emergency.

To put parents’ minds at ease, Harte says trip leaders post information and photos of what the children have been doing every day on the school website.

Consequently, she says, homesickness is never a problem.

Snape takes a similar approach in so far as students at The Spinney are not allowed to take their mobile phones away with them.

“They don’t need to phone home because we make it very clear to parents that they are going away, they’re going to be with their friends and their teachers, and unless there is a problem, the parents won’t be contacted.

“It’s the anxiety about contact that actually makes them more homesick. It’s about allowing the children to focus on where they are and the experiences they are having with their friends.”

She has also adopted a novel approach to ensuring that those children who like to bring a home comfort with them are not singled out.

“I say that no child will be allowed on to the bus unless they take a teddy bear or whatever comforter they have to go to sleep with,” she says.

“The reason I say that is that some children won’t need it but we don’t want the children that do to feel lesser because they need to take their teddy bear.

“We make it a blanket requirement. I have a collection of four different teddy bears for any child that fails to bring their own.”

Waiting at the gates

Even if you’ve got through the trip without incident and followed everything above to the letter, you’re not out of the woods yet.

Whether the activity itself overruns or you find yourself caught up in traffic on the way home, it’s often the case that school trips run late.

So what should a teacher do if it looks as if they are going to miss the drop-off time back at school?

Teachers agree that modern technology has made dealing with such eventualities far easier than in times gone by.

“Before about 10 years ago, it was a nightmare,” says Elliott.

“You’d either get back early and be waiting for the parents to turn up or the parents would be waiting there for ages.”

Harte says the school will post on its website what time students are expected back so the parents can check the website before coming to collect them.

In the event that parents are already on site, staff on the trip will provide regular updates to school staff who, in turn, will keep parents informed.

Communicating with parents

Social media is an especially useful tool for communicating to a wide network of parents. Elliott notes that Tor Bridge High School has a hashtag for all of its trips that is communicated to the parents, who can then check on their child’s progress.

O’Brien, meanwhile, points to the effectiveness of a WhatsApp “parent tree” whereby a few key parents receive school messages regarding the trip and then cascade the message to other parents in their tree.

Despite all of this, there will still be incidences when parents are not waiting to collect their child at the end of a trip.

Often parents will simply be running late but, on rare occasions, they won’t turn up at all. In this situation, there are obvious safeguarding risks around offering a lift home to children, which need to be considered.

Pountain says that taking a pupil home alone in the back of your car is bad practice for a teacher and not just because of the risk to the child.

“If a child makes an allegation against you, it’s simply your word against theirs and you want to avoid that at any cost.”

Grierson’s advice is to take a child home only if the relevant insurance is held and you are accompanied by a second member of staff. In such situations, you must ensure that the child travels in the back seat with a seat belt on.

Nick Hughes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters