Education secretary Bridget Phillipson says that, as a nation, we can do better at maths. She’s right - we can. And what’s more, we should.

Because maths doesn’t just change the world; it changes how you see the world. To a mathematician, every obstacle is just a puzzle to be solved.

A true understanding of maths allows one to imagine things never before imagined, to see beyond what others have seen and to solve unsolvable challenges.

And it appears that I’m not the only maths fan around.

A nation of ‘secret’ maths fans

A new in-depth report looking into the state of maths in British society, commissioned by Axiom Maths, shows that the UK is a nation of “secret” maths fans and there is strong support for more maths education.

Rather than the UK being a nation of anti-mathematicians, we are actually a nation of shy mathematicians. Nearly half of us say we actively enjoy doing maths. Very few of us believe that mathematicians are anti-social.

Around three-quarters of us think that maths is critical for our economic future, and that children should learn more of it for longer. We don’t talk about maths, but we believe it is important - and, whisper it, we even like it!

Maths engagement in schools

It’s fascinating to uncover this hidden appreciation of maths when so often what we hear is that people don’t like maths or are scared of it. It’s the subject we seem to hate but also want our kids to love.

People are keen to see maths taught in schools for longer - with 72 per cent of people in support of the principle of maths to 18, including a majority in every age group.

More from David Thomas:

Almost half of all parents (48 per cent) say they would like their 11- to 16-year-old to study maths at A level - a higher proportion than said the same thing about English language (36 per cent).

A majority (52 per cent) say that maths will be important to their child’s future job prospects - the highest proportion for any subject tested.

Busting the ‘maths geek’ myth

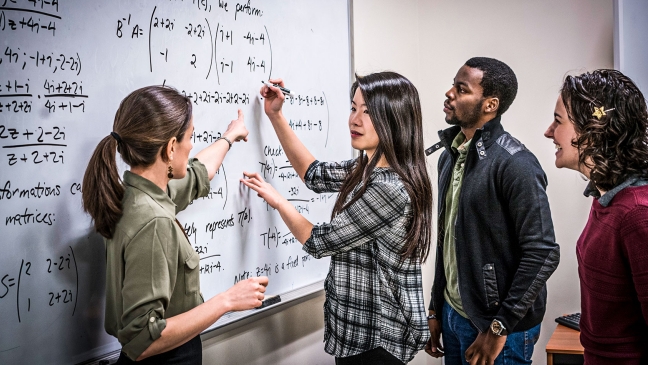

The stereotype of the “maths geek” isn’t real, the study suggests. In our research, mathematicians were more likely to identify as extroverted than non-mathematicians were. And being perceived as being good at maths doesn’t put others off either - if anything quite the opposite.

Respondents to our poll were three times more likely than unlikely to go on a date with a person if they knew they were “really interested in maths”.

The old stereotypes have long outlived their shelf life, and it’s time for this nation of secret maths lovers to step out from the shadows and be loud and proud about the power of maths.

Supply of Stem graduates

This research should give us the confidence to fight back against those who proudly talk down maths, and wear their dislike of it as some sort of badge of honour.

And we need to seize on this to nurture a new generation of confident mathematicians.

Around a quarter of children score highly in maths at age 11. As work by the University of Nottingham shows, 30,000 of these children in every year group won’t go on to achieve top grades in the subject at GCSE. Somewhere along the way these bright-eyed and bushy-tailed mathematicians go missing.

And if that wasn’t bad enough, this attrition rate is around 50 per cent for children from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

We know that, as a country, the pipeline of mathematicians is running dry - England alone has a shortage of 16,000 skilled mathematicians in its workforce. Our children are becoming top mathematicians at half the rate of a country like Singapore.

Just imagine 30 average-sized secondary schools full of talented maths minds disappearing from our country every year. This number of students could fill the UK’s current skilled science, technology, engineering and maths (Stem) vacancies more than twice over.

The teaching workforce will, of course, be critical to supporting a pro-maths future. Although the total number of maths teachers has risen consistently over the past decade, the number recruited last year was less than two-thirds the Department for Education’s target.

Meeting the demand for maths

But there is an opportunity to think differently about how we meet the maths demand in our secondary schools.

Our primary schools have shown just what is possible when it comes to maths - our Year 5 maths score in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timms) has gone up consistently for 20 yeas, and only seven countries in the world score statistically significantly above us.

At the same time, given the demographic squeeze that will lead to many primary schools getting smaller, there is no reason why key stage 2 primary teachers could not deliver key stage 3 maths.

Yes, there would need to be some additional training, but the continuity in delivery that this would provide, building on the great work in Years 5 and 6 going into the early part of secondary school, and keeping those maths minds keen and on track, would be more than worth the time that would take.

The tide is turning - we now know that the public are not, in fact, a nation of maths refusers. They are really very keen, if a little shy.

The new government’s curriculum and assessment review provides a great opportunity to capitalise on this and build on the great foundations that we have in primary.

Instead of being shy about maths, let’s give our bright young maths minds the chance to keep shining, and say goodbye once and for all to the maths naysayers.

David Thomas is CEO of Axiom Maths

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter