Scottish school leadership: the head in charge of six primaries

The journey to Brodick Primary School on the Isle of Arran hugs the coastline, squeezing past shops and hotels on the sinuous high street, as well as the numerous imposing houses that overlook the Firth of Clyde. Many gardens have palm trees - even the local Co-op has some in the car park - which is an incongruous sight at this time of the year, given that the island is covered in snow.

There were snow showers all last night, and headteacher Shirley MacLachlan had a nail-biting journey this morning up and down “The String” - the road that links the west and east of an island that is essentially one very big hill - to welcome a new member of staff to Shiskine Primary.

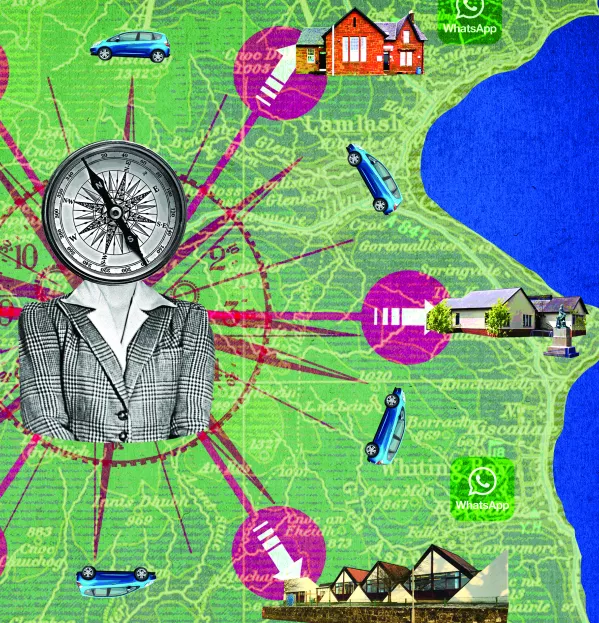

Brodick and Shiskine are just two of the schools MacLachlan leads. Also under her charge are four other Arran primaries - Corrie, Kilmory, Pirnmill and Whiting Bay - making her unique in Scotland: no other head leads as many schools. There is only one primary on the island that does not have her as headteacher.

‘Radical solution’

When the post was created in 2016, MacLachlan heard the new set-up being described as “one school over six campuses”. But the reality is far from that, she insists, because each school is distinct from the others. Each has its own start and finish times, as well as its own emblem: at Brodick, it is the stag; at Kilmory, the heron, and at Whiting Bay, the swan.

In Whiting Bay, a lot of affluent newcomers have arrived to live in recent years. Corrie, meanwhile, is something of a cultural hub with its poetry competitions and Sunday cinema. Each village has a football team and its own Christmas party, where every child gets a present.

Brodick and Whiting Bay are the largest schools with about 60 pupils; Pirnmill and Corrie are the smallest with 11 and nine, respectively. These are one-class schools in which all children, from P1 to P7, are taught together. Kilmory has two classes, but the school is open-plan with the “wee class” and the “big class” separated by bookshelves that create a little library area in the middle of the room.

Seeing for the first time how the single-teacher schools worked in practice - and the scale of the challenge - has been one of MacLachlan’s abiding memories from her early days on the island.

MacLachlan, formerly a depute headteacher for four years at Wallacewell Primary in Glasgow, could travel around all six schools in a day, but it would be a whistle-stop tour and a meaningless exercise, she says. Seeing as the schools are fairly evenly spaced around the rim of the island, it would essentially mean doing a lap of Arran, which, despite being just 55 miles in circumference, has narrow, twisting, undulating country roads that stretch journey times.

Today, all the schools are open but driving conditions are hazardous, and some teachers have been forced to attend the primary nearest to their home rather than the one in which they usually work.

Yet, even in more clement weather, the logistics of MacLachlan’s job are far from straightforward. “Other headteachers say ‘how does that work?’ because there are not even enough days in the week to be in each school for one day,” she says. “The answer is you have to be partly responsive to situations and you also have to have a bit of structure as well. I don’t want to spend my day in the car so I try to go to a school and stay there.”

MacLachlan’s goal is to spend at least one day per week at the larger schools - Brodick and Whiting Bay - and then to visit the four smaller schools once a fortnight. She does, however, have two deputes to share the workload: Jane Boyle, who was already working on the island when the restructure took place; and Quinton Black, who was raised on Arran and relocated from the mainland to take up the post. Boyle and Black are responsible for three schools each and they spend time in all three every week. There are also two principal teachers based in the two largest schools.

The current structure costs slightly more than the previous one, which involved three headteachers working across the six schools, but no deputes, says John Butcher, who oversaw the changes as North Ayrshire’s director of education and youth employment. Brodick, Pirnmill and Corrie shared a headteacher latterly, as did Kilmory and Shiskine, but Whiting Bay had its own head.

According to Butcher - who is now an education consultant, having left North Ayrshire Council in August - the aim was to avoid closing any schools, while also improving consistency in the quality of learning in each.

Sharing the headship between multiple schools also meant a larger salary could be offered to candidates for the role, which improved the chances of a high-quality candidate applying, he adds.

Butcher explains: “I would acknowledge it was a radical solution, but we had to work out how to get the best for the island. If you have a headteacher post that has a small salary, attracting the right people and the right quality of people is very difficult.”

MacLachlan says she faces the same issues as other heads: not enough staff, not enough resources and not enough hours in the day. The difference is that she faces these issues “in a number of different locations”.

It is a tough shift. The three school leaders have generally worked their 35-hour week by close of play on a Wednesday, and because they are often in different schools at different times - and because they don’t always have mobile phone reception and often rely on school wi-fi - they have their own WhatsApp group. Messages can start pinging back and forth as early as 6am and don’t generally stop until 8pm.

Island life not plain sailing

Some statistics throw into sharp relief the scale of the challenge MacLachlan faces. In a typical school year, there will be 24 parent council meetings, 16 parents’ evenings, 18 church services, six Christmas shows and six summer fayres. So one of the first things the senior management team did after their first full year in their new roles was to take a close look at the various school calendars.

“We had a meeting on the first day of the summer holidays,” recalls MacLachlan. “We were in here at 8.30am until 5pm looking at the calendar and deciding when we would have parents’ nights and when we would do the Christmas services. Everyone wants it on the last day because it has always been that way and in the first year we tried to accommodate that but, inevitably, because things overrun, I ended up being half-an-hour late for the last one and arrived just as the kids were being wished a happy Christmas.”

Plans are now afoot to bring all of the schools into sync with their start and finish times, breaktimes and lunchtimes.

MacLachlan has always been a regular visitor to Arran - she named a pet black Labrador “Corrie” after one of the villages before she had any inkling she would ever be living here. Corrie still lives on the mainland, as do MacLachlan’s son, Kai, who is in his final year of secondary, and husband, Gordon. Come the weekend, someone is getting on a ferry.

MacLachlan likes that she still gets to regularly indulge in what urban life has to offer but, during the working week, finds herself in one of the most stunning settings on the planet where, when travelling to Pirnmill Primary, she can spot seals dotted along the beach.

“I think some people might have looked at the job and thought ‘I can commute’, and there are people on the island who do commute…But for me, the whole point of coming to Arran was to be on Arran.”

MacLachlan jokes, though, that when she and her husband first worked out the financial implications of the new living arrangements, it looked like she would have to live in a tent. As it turned out, she found a nice three-bedroom bungalow in Whiting Bay. But there is a serious point to be made here: the cost of living on the Isle of Arran is prohibitively high. A lot of the work is seasonal and tied to the tourist trade, and many families struggle.

MacLachlan sees friends in mainland schools receiving hundreds of thousands of pounds via the Scottish government’s annual £120 million Pupil Equity Fund (PEF), which puts cash straight into the hands of school leaders. But the criteria used to distribute the money is the number of children at each school with free-school-meals entitlement; like many rural school heads, MacLachlan feels that this measure underestimates the level of poverty of some of her pupils. Many families will not claim free meals because of the stigma it carries, and the dearth of social housing on the island means expensive private lets are a drain on family income.

“I’ve got no PEF money for Pirnmill and very few [pupils claiming] free school meals, but I’ve also got families that live in caravans,” she notes. “The big thing on Arran is accommodation: because house prices here are so expensive, people find it very difficult to get on to the property ladder and there’s very little social housing, which forces people into private lets.

“If you [own] a private let, you can rent it out for £700 a month [to island residents] or as a holiday home for £500 per week in the summer, so there’s a decision to be made [by landlords] there.”

A 2017 report by the Arran Economic Group found that the island was second only to London in the UK for difficulty in accessing affordable housing. There is no council housing on the island, but 342 social housing properties are operated by Trust Housing Association (covering 16 per cent of households) and plans are in place to build 26 council houses in Brodick.

James McEnaney is now an English lecturer at a Glasgow college but, between 2011 and 2014, he was an English teacher at Arran High School. He would have loved to have raised his son, who is now 4, on the island, but that proved an impossible aspiration given the cost of living. Housing is “a nightmare” and the lack of healthcare is also a barrier.

While an island upbringing does appear idyllic, MacLachlan is also aware that cultural experiences, such as going to museums or the theatre, can pass her children by. Still, students are presented with opportunities to expand their horizons: over the course of a morning at Whiting Bay, I meet the Chinese teacher based on Arran, Dong Lu, who delivers Mandarin lessons to senior primary pupils in all of the island’s schools, and will do so for the next two years. I am also introduced to piping teacher Ross Miller.

The latter - fresh from the final of the BBC Radio Scotland Young Traditional Musician of the Year 2019 - is just off the ferry and rounding up pupils to deliver his weekly music lessons. Each of MacLachlan’s primaries teaches different instruments - at Whiting Bay, pupils learn the pipes and drums; at Brodick they play the fiddle; at Corrie, the clarinet; at Kilmory, the trumpet; at Pirnmill, the saxophone; and at Shiskine, brass instruments.

Inevitable compromises

The adjustment to the new management structure has arguably been hardest for Whiting Bay, as it retained its own headteacher for longer than the other schools. The 50-year-old listed school building, situated cheek by jowl with the beach, has a zigzagging roof and facade designed to reflect the sails on boats and its three classrooms all have stunning views across the Firth of Clyde.

Raye Beggans, a principal teacher who takes the P6-7 composite class, was acting head of Whiting Bay prior to the restructure, but chose not to apply to lead all six schools. She regrets that there is not always a leader around to deal with issues as they arise.

This is pretty much a constant refrain among staff I meet. However, the teachers do highlight positives, including that there is now more joint working across the schools, as well as better sharing of resources. Staff undertake professional development together, and when the P6 residential takes place each June, pupils come from all six schools.

Local minister Reverend Elizabeth Watson, who has lived on Arran for 34 years, is sanguine about the changes. The key thing, she says, as she wraps up her fortnightly assembly at Whiting Bay, is that a solution was arrived at that staved off any school closures. To lose the local school would have been devastating for any one of the communities involved, she believes. “When I first came here, all the schools had one headteacher, which would be ideal, but everybody recognises the way things are with the small numbers [of pupils] and the costs, that things have to change,” she says. “This community, I feel, is always ready for change and embraces it, and from what I’ve seen, it’s working fine.”

When Watson arrived on the Isle of Arran, there were four ministers, but when she retires in three years’ time, there will be just two. It is hard not to draw parallels: just as the Church is having to make difficult decisions in the face of dwindling congregations and resources, so too are local councils about schools.

A report into headteacher recruitment - uncovered in February through a Tes Scotland freedom-of-information enquiry - found that the number of heads working across more than one school in Scotland had risen by 64 per cent between 2010 and 2017, increasing from 118 to 194. However, the document questioned whether this growing band of school leaders was being adequately remunerated (see box, above), and MacLachlan queries whether the inspection process is equipped to account for this increasingly common model.

Whiting Bay was inspected during the first year in which she was in charge, but she argues that her schools have to be looked at in the round, otherwise she faces the prospect of never-ending inspection.

Another 20 minutes around the coast from Whiting Bay, past MacLachlan’s favourite view, which takes in the uninhabited islands of Ailsa Craig and Pladda, is Kilmory Primary, where the air is electric with excitement. Tyler is about to add vinegar to a papier-mâché volcano and make it “erupt”.

The local community is worried about the roll: 20 pupils currently attend the two-class school and, if numbers drop further, a teacher could be pulled. It is hoped, though, that a new whisky distillery, visible from the playground, will bring work to the area - as well as more children.

As we leave Kilmory, we bump into Peter Bowers, who is out walking his dogs. He is a dad to three children at the school, in P3, P5 and P7. Bowers owns the nearby Lagg Hotel and has lived on Arran for 15 years. As head of the parent council at the time of MacLachlan’s arrival, he was concerned about the logistics involved in the new leadership structure. It might make sense to someone at a remove from the island to put six small schools in a relatively compact geographic area under the leadership of one head, he argued, but on Arran, it can take an hour to drive 16 miles.

However, Bowers now admits that he has been “pleasantly surprised” by how the structure has worked in practice, describing the effort put in by the new leadership team as “above and beyond”.

“She deserves the fancy Alfa,” he says, referring to MacLachlan’s new car, adding: “It’s still a challenge - [the shared-headship situation is] not ideal - but compromises have to be made if you want schools in remote places where there are small numbers.”

For all the initial misgivings, the new set-up appears to work, although it demands committed professionals who put in many extra hours.

As for MacLachlan, her work situation on Arran may be unique in Scotland, but she is “absolutely delighted” that she took on the challenge.

Emma Seith is a reporter for Tes Scotland. She tweets @Emma_Seith

This article originally appeared in the 1 March 2019 issue under the headline “Hit for six”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters