A group of elite middle-distance runners gathers at an athletics stadium, hopeful of gaining a spot in the national squad. The coach issues them with the challenge: “Run 1,500m in under 3 minutes 45 seconds and you’re in.”

“Now? Here?” asks a runner. “No,” replies the coach, “do it whenever you like. Just time yourself and email me the result when you’re done. And make sure it’s under 3 minutes 45 seconds.”

This, of course, would never happen. Yet teachers are regularly held to account on the basis of their own assessment data. In what other industry would employees’ performance be assessed using only the information they supply?

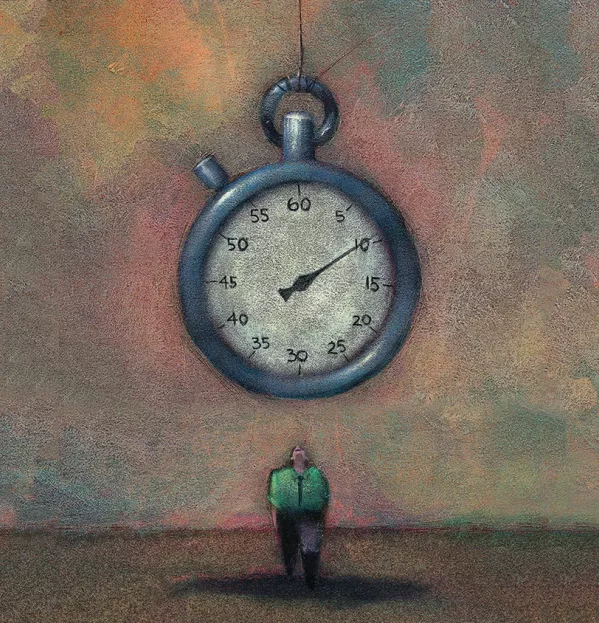

It is little wonder that pupil-tracking - a process that should be about evaluating whether pupils have understood what’s been taught - has been reduced to a time-consuming exercise more focused on giving the right impression than providing a warts-and-all picture of learning.

Teachers are under pressure to ensure that the data they collect conforms to the desired narrative and the risks of this are clear: under such circumstances, data can easily be distorted. This is particularly true where the same assessment is being used to monitor pupil performance and also used as evidence for staff performance-management purposes.

‘The primary purpose of assessment’

The final report of the Commission on Assessment Without Levels warned of these risks in September 2015. The report advises school leaders to “be careful to ensure the primary purpose of assessment is not distorted by using it for multiple purposes”.

Meanwhile, the Workload Review Group’s 2016 data management report stated that teacher assessment-driven pupil-tracking data “can be used to draw a wide range of conclusions about pupil and teacher performance, and school policy when, in fact, information collected in such a way is flawed.”

Despite these warnings, our accountability system relies heavily on teacher assessment. Early years, phonics, key stage 1, and writing at key stage 2, all of which are teacher-assessed, appear in the inspection data summary report and are used to monitor school standards. This is perhaps the most pernicious use of tracking data in primary and secondary schools.

Pupil-tracking data should be used solely to support learning. The widely held belief that school and teacher performance can be evaluated using the data that teachers generate has resulted in a tug of war, with competing forces pulling assessment in opposite directions.

The choice is between accurate data for teaching and learning, and distorted data for accountability. All senior leaders and external agencies, including local authorities, Ofsted and regional schools commissioners, need to wake up to that fact. We can’t say we weren’t warned.

James Pembroke is the founder of Sig+, an independent school data consultancy (www.sigplus.co.uk)