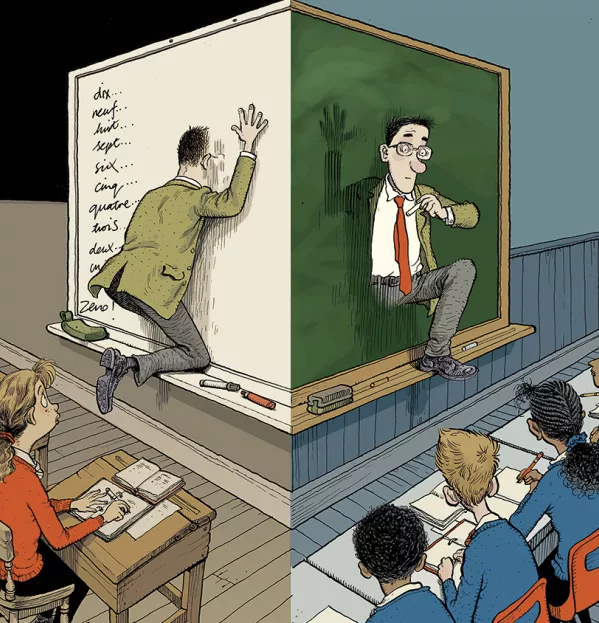

A tale of two settings

Much has been written on the essence of outstanding teaching: high expectations, no excuses for underachievement, firm boundaries, knowing your students and scaffolding the ascent to success. Simple.

I have always believed that I am an outstanding teacher. I have been practising what I have known to be true about exceptional teaching in a range of contexts since I entered the profession six years ago. But never have the contrasts of what constitutes exceptional teaching in context been so clear to me it was during the past autumn term. What had changed? Allow me to explain.

On blustery Sunday nights, I did what I’m sure many teachers across the country spent the end of the weekend doing: preparing for the week ahead. But my days looked very different to most other teachers. I’ll give you an example.

Monday morning

At the start of the school day, students would line up. I’d raise my hand and silently count down to zero, whereupon key stage 3 would fall silent (the conscientious ones nudged those less observant). I greeted the students and they followed their tutor in silence to registration. I may have had the luxury of “losing my temper” about a top button being undone, or a student shuffling their feet while I give instructions, but I probably didn’t.

I’d planned my lessons. I had a rough idea of what I needed to achieve with Year 10 and Year 13. Year 10 needed pushing to include more complex structures in their written and spoken French, so all the activities were aimed at extracting advanced vocabulary from texts and applying them. There was lots of pair work (approximately 35 of the 50 minutes), no PowerPoint presentation, no objectives written in their books - just lots of French. Year 13 needed lots of modelling of analytical thought to move on in their literature writing, so we studied several model responses, analysing and improving exemplary work. They were asked to redraft their essay in full for homework.

Monday afternoon

Line-up post-lunch was a very different beast. I met Year 9 in the playground and explicitly told each student where to stand; this needed repeating, as they tried to change places to stand with their friends; then the countdown (this time at full volume) finished. Students who were still talking received a detention; pupils needed reminding about uniform several times; finally, we walked to the classroom. On the way, I had to stop at least three times to regroup the line and reinforce expectations of silence. More students received a detention for not following instructions.

My Year 9 set got back their exercise books, in which most students achieved a grade 1 in their recent assessment. I used green highlighter for the good parts and pink highlighter for sections that need redrafting.

They needed something calming to do at the beginning of the lesson, while I recorded the names of students without pens on the board, and then issued the pens. During the starter, I collected their homework and placed this week’s task on their desks. I included a countdown in my PowerPoint slides, and this helped with focus.

Before peer-marking the starter, I set the homework and checked everyone had the details in their diary. I planned an energetic activity, but included a slide involving lots of writing just in case the more adventurous task went pear-shaped.

I had to re-establish expectations with the student I placed in isolation last lesson and I had a “reserve seating plan” in the back of my mind in case my intended pairings didn’t work. Pair work was minimal, and there was lots of controlled writing to keep students on task. The objective of the lesson was visible on every slide of the presentation; I returned to it several times to keep everyone on task. My last observation suggested I needed to move more quickly through the behaviour system, so I kept this in the back of my mind as the lesson proceeded.

Why were the two halves of my day so different? Well, between September and Christmas, I worked concurrently as assistant headteacher at a small independent school, as well as a part-time French teacher at a large inner-city academy. The demands of my job changed enormously as I made the short (approximately six-minute) journey between schools.

Scale fundamentally changes the nature of the teaching experience. In my department, there were around 100 students studying languages. In contrast, there were 210 students in each year group at the academy. Systems need to be more robust and lines of accountability much clearer when you are looking after 1,000-plus students.

I could name every child at my home school, but I was a stranger to all but two classes in the academy. With the knowledge of a child’s name, you have the beginnings of immediate rapport and the potential to make behaviour management around the school substantially easier. No teacher, however long they have worked in a large school, has this knowledge.

All schools have different cultures; working in two extremes was illuminating. I was able to joke, laugh and relax with students at my home school, with the raising of an eyebrow sufficient to quash any low-level disruption. I could take risks, go off-piste and dive into rabbit holes of learning, as structure, routine and order were less of a concern. Meanwhile, at the academy, a room change and an increase in the wind speed was enough to bring a Year 9 lesson to its knees. The teaching experience was fundamentally less pressured, less stressful, and less physically and emotionally exerting at my home school, as so much deferential behaviour was simply taken as a given.

This experience left me perplexed at the notion that independent schools should take a leading role in the national school-improvement journey and that independent schools have “the model” for successful schools. Independent schools do an entirely different job to their non-fee-paying counterparts: they have different students and different priorities, not to mention different challenges. To suggest that one could take anything that worked in my home school and implement it at the scale of most non-independent schools is laughable. The country is peppered with successful schools in comparable contexts to schools in greater difficulty - and they would be in a much better position to offer support.

I am similarly challenged by the idea that outstanding teaching is something that can be learnt on a course, in a book or via Twitter. As an avid reader of pedagogy and a regular contributor to the teacher Twittersphere, on many occasions my grand designs have either fallen apart or proved less effective than the ideas of colleagues with more contextual experience. A watertight understanding of how things should be done does not necessarily equate to an ability to deliver.

Educationalist Dylan Wiliam’s oft-cited adage that everything works somewhere, nothing works everywhere, rang true on a number of occasions during that term. This realisation has implications for teacher training, people looking to move between schools in contrasting circumstances, and leaders operating across different contexts. A period of familiarisation with, and understanding of, the context is critical before any progress can be made.

So what now for me? Having spent three years in senior leadership at an independent school, I left in the new year to take up a middle-leadership post in a large academy. I have high hopes for my career and I hope that, in time, these ambitions will be realised. Reading widely, speaking at conferences, writing a blog and contributing to the education debate probably won’t hurt in that process, but it was not enough to do this and work in such an atypical environment at the same time.

I’ve said goodbye to small classes, optimum working conditions, compliant students and long holidays, and hello to something quite different. I’ve got to grips with a new context, re-evaluated my teaching style and blended what I know to be effective with what will deliver results in a different culture.

What did I learn from my experience? Context counts for more than you’d think.

Dan MacPherson is assistant headteacher at Greenwich Free School. Prior to this, he was assistant headteacher and head of modern languages at North Bridge House Canonbury, an independent senior school in London. During that time, he completed a part-time secondment at a nearby academy

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters