Teachers should acquaint students with the first environmental activists

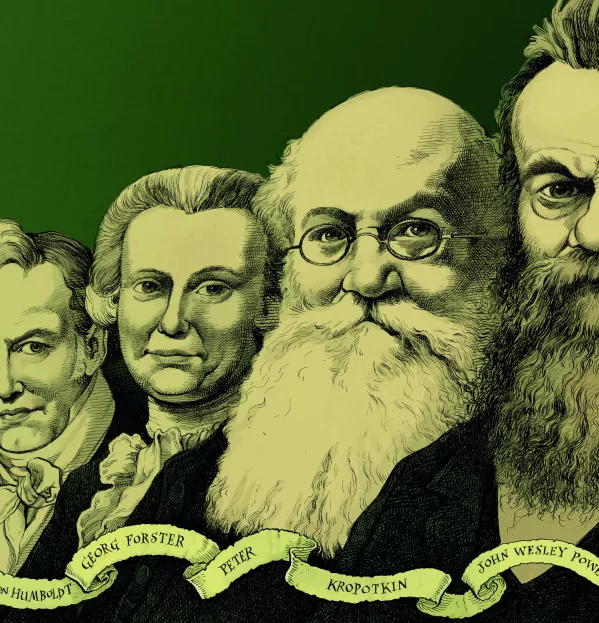

What do the following have in common? A one-armed American Civil War veteran, a Russian prince with a prison record, a German teenager taking a trip around the world on a converted coal freighter and a Prussian polymath who gave his name to currents, cacti and counties? Oh, and a French anarchist and anti-marriage naturist.

Between them, this unlikely quintet changed our view of the way people interact with the natural world. And for all their differences, they shared a commitment to understanding and educating the world that led them beyond ideas to action, often at great personal cost. At a time when the environment and its fragility, and climate change and its consequences, increasingly exercise the minds of people not paralysed by Brexit, and when youth-led protests are urgently demanding action, it is time to re-acquaint ourselves and our students with these voices from the past who cleared the path for evidence-informed activism.

Climate change - and, in particular, human-induced global warming - has, until recently, occupied a peripheral place in politics and in education. For decades, mainstream political parties have paid lip service to radical environmental policies only to shelve them on attaining power. Politicians have been taken by surprise at the current upsurge of concern and protest, led largely by the young. The calls have been not only for action but for education. An online petition set up by school pupils called for climate change to become a core part of the curriculum and the Labour Party hastily climbed aboard the zero-emission bandwagon.

The national curriculum, reviewed only a few years ago, already seems hopelessly out of date, notwithstanding government assertions that climate change is satisfactorily dealt with. Science in key stages 3 and 4 covers the impact of carbon dioxide on climate, and accommodates the debate about human causes of climate change. But, for a broader, integrated perspective on the relationship between people and the environment - connecting up all aspects of climate change, water supply, landscape degradation, ecosystem fragility and resource management - we have to look to geography, which is not even studied by all pupils beyond age 14.

The science of human-environment interaction is coming into conjunction with politics in a way not seen for centuries.

Among the founders of modern geography, there are some remarkable, yet now almost forgotten, individuals who put the environment at the centre of their work and weren’t shy of making it political as well as personal. Alexander von Humboldt, once the world’s most famous scientist, explorer and geographer, is now scarcely remembered. When he finally succumbed, in 1859, after a long and eventful life, he was well-known enough for the headline in The Times to read simply, “Alexander von Humboldt is dead”. To Darwin, he was “the greatest scientific traveller who ever lived”, and King Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia called him “the greatest man since the Deluge”.

Humboldt pioneered meticulous scientific fieldwork in his travels in the Americas, and was equally at home studying plants in the rainforests of Central America as he was discussing geopolitics with Thomas Jefferson, then US president, in the newly built White House. His name is memorialised throughout the New World in place names, mountains, rivers, glaciers, bays and an ocean current, as well as species of bat, monkey, penguin, skunk, squid and dolphin, and varieties of cactus, orchid, mushroom and oak.

Politics and nature

Humboldt pioneered a vision of nature as an interconnected system and, in fact, he revolutionised the way we see the natural world today. His concept of the web of life within which no single fact can be seen in isolation was a clear progenitor of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and James Lovelock’s concept of Gaia. He was the first scientist to talk about human-induced climate change, and dwelt on the devastating environmental effects of deforestation in Venezuela, which he associated with the evils of colonial exploitation. For Humboldt, politics and nature belonged together.

Humboldt had met and been influenced by Georg Forster, the voyager, naturalist and revolutionary. Forster made his name writing at first hand about Captain Cook’s second circumnavigation of the globe from 1772-75 (Forster was a teenager at the time), becoming an expert in the ethnology of Polynesia and a professor of natural history. He saw cultures as developing in relation to their environments, and wrote of the irony of “civilised” Europeans professing shock at cannibalism in New Zealand while being happy to slaughter each other on battlefields.

Forster shared with Humboldt a vehement opposition to slavery and he took the view that there was “too much writing, too little action in the world”. Nevertheless, he arranged for the translation of Paine’s Rights of Man, and wrote the foreword to the German edition. He supported the French Revolution (growing his moustache to signify support for the regicides), and became vice-president of the first republic on German soil. His reward was to be outlawed after the Restoration.

Elisée Reclus was a geographer and an anarchist. The author of a 19-volume tome on the geography of the world, focusing on the interaction of people and environment, he supported the 1871 Paris Commune, for which he was imprisoned and exiled. His work was both academic and action-orientated, and his approach has been seen as “scientifically sound and morally uplifting”. He was also an opponent of marriage and clothes (he considered one overly restrictive and the other unhygienic).

Peter Kropotkin, a friend of Reclus, was also an anarchist and a geographer, but combined these with being a Russian prince. His theory of mutual aid placed cooperation as the basis of human nature. Unwilling to make his appeal on the basis of either religious faith or abstract metaphysics, he used examples of relationships in the natural world to establish the basis for a moral standard. His politically radical concept of human ecology was based on the idea that people in nature are part of an organic, interrelated whole, with actions in one part affecting all the others. Interventions in nature, he felt, should be based on respect for, and understanding of, the natural world.

Lone voices

Kropotkin was a political activist who spoke out against illiberal regimes and was imprisoned several times in several countries. But he was feted by the geographical establishment (his best friend was John Scott Keltie, secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, who championed geography as an academic subject and lobbied for the admission of women as fellows to the hallowed halls at Kensington Gore).

One of Kropotkin’s first acts in 1889, following a spell in a French prison, was to give a lecture to the Manchester Geographical Society on geography as a means of developing humanitarianism as well as a discipline of thought.

John Wesley Powell lost his arm fighting for the Union in the Civil War, after which he became an explorer, geologist and ethnologist. He led the first official exploration of the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon in 1869, and became director of the US Geological Survey. He also investigated the languages and lore of the indigenous peoples in the mountain West, and championed the rights of Native Americans, becoming the first director of the Bureau of Ethnology. He was vocal in opposing unrestricted settlement and intensive agriculture in the arid lands, using meteorological data to disprove the prevailing theory that “rain follows the plough”. In a report to Congress, he advocated low-density development, water conservation and cooperative farming in the arid region. His ideas, ignored at first, gained traction only in the experience of the 1930s Dust Bowl.

Each of these was a lone voice but highly influential in the aggregate, albeit delayed by several centuries.

Clarence Glacken, cultural geographer and pioneer historian of ideas about the environment, put it aptly: “Large related bodies of thought thus appear, at first, like distant riders stirring up modest dust clouds, who, when they arrive, reproach one for his slowness in recognising their numbers, strength and vitality.”

In linking people and environment, and in drawing attention to the calamitous cause-effect relationships that oftentimes ensued, these intellectual outriders recognised no boundaries between information, ideas and activism. For them, the natural was political and the political personal. Today’s young people, increasingly attuned to the need for urgent action on the environment, deserve to become acquainted with them. Sorry Oxford, but perhaps we need a new-style PPE: people, politics and environment. Or we could just reclaim for geography its rightful place in the school curriculum.

Kevin Stannard is director of innovation and learning at the Girls’ Day School Trust

This article originally appeared in the 19 July 2019 issue under the headline “On the shoulders of eco giants”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters