Teachers want to be scientists, too

As a physics teacher, there is nothing I love more than picking up on the latest advances in my discipline, whether it be the discovery of gravitational waves or discussion of my particular research area, the philosophy of quantum mechanics. It comes as little surprise to me that there is a growing body of evidence that subject-specific CPD improves teacher retention and satisfaction.

But is that enough?

Is an update from a fantastic research group or leading professor the limit of the link between research and teaching? Unfortunately, that seems to be the norm in science - but it’s not in other subjects.

Most music teachers wouldn’t dream of not practising their subject, yet in science there is a discreet divide between school science and the practice of science, and the notion of a teacher-scientist is all too rare.

This is a pity because it is undoubtedly true that if teachers feel they are contributing members of the science community, they enjoy teaching more and find the profession more appealing. I was at a meeting on science education where the organiser said, “Hands up all the teachers, and hands up the scientists” - I somewhat rebelliously put my hands up both times. Imagine this for music - those who were teachers and those musicians - the question wouldn’t be asked. And if it was, all the hands would go up on both occasions.

Why has this split between teaching and doing science taken hold in our schools system? The complete opposite is held dear in universities - research-led universities pride themselves on the fact that teaching is informed by research.

Schools are increasingly involved in research into pedagogy and making an evidence-based profession. That’s great, but teachers also love their subject and want to maintain a research connection to their subject community.

When I meet young scientists finishing their degrees or PhDs, there is often a great wish to inspire others with the excitement and thrill they feel for their subject. Some worry that teaching won’t enable them to maintain their research interest. This could be different. I went into teaching with the same ideals, to encourage people to love physics and be inspired by the universe.

If scientists finishing their degrees are put off teaching by the perception that they’ll lose touch with their subject and that the subject they teach at school is somewhat removed from their experience of science, then it’s time to address these issues.

And so I built a different model, one in which I could work with students on cutting-edge research as part of my teaching, and that has generated so much enthusiasm and interest for me and them. The teacher-scientist model brings the teacher into the science community and gives them a professional identity as both a scientist and teacher.

My class and I even commissioned a groundbreaking experiment in space. When we got the results down from our payload in space, we all had to learn together. There were no answers at the back of the book. It certainly made me a better teacher, and my experience of learning with students was invigorating.

The Researchers in Schools scheme supports training teachers to have a day a week to keep up their research. This model could be available to experienced teachers, too. Some education leaders are supporting this, seeing improved attainment and progression for the students and improved retention for their staff. Projects include Authentic Biology and Genome Decoders.

Teachers appear to enjoy these programmes. Some who have come from research would say: “After leaving research to become a teacher, I sometimes hanker after those moments of discovery at the cutting edge, but Authentic Biology allows me to rediscover these moments alongside young people. After a few years out of research, you could feel deskilled and that you are missing out on the latest progress, but being involved in Authentic Biology, discussing our research with scientists in the field, allows me to keep abreast of current thinking, which makes me a better teacher.”

And others, who feel that it reconnects them with their science, would say: “When I first began teaching, I saw myself as scientist who taught young people science, but over the past few years that sense of being a scientist had begun to fade. Working on the Genome Decoders project has connected me with leading scientists working in the cutting edge of genetics research and this has enabled me to see myself as a professional who is a teacher, but also as a scientist. This experience has helped me to realise that I have something to contribute to the science world as well as the teaching profession.”

The teachers who work with us, being given the time to tackle cutting-edge problems with their pupils, say that this experience gives students a realistic experience of science and that they love the chance to genuinely contribute and have some agency.

The teacher-scientists and students have recently, for example, contributed to a project analysing Higgs Data from the Large Hadron Collider, supported by Professor Alan Barr at the University of Oxford. “The draft results from the students look very impressive indeed,” Barr says. “The students are asking interesting research questions, many on topics we had not anticipated. They are developing novel algorithms, analysing large data sets, and have presented clear results. I’m greatly looking forward to discussing their research with them in person in Oxford.”

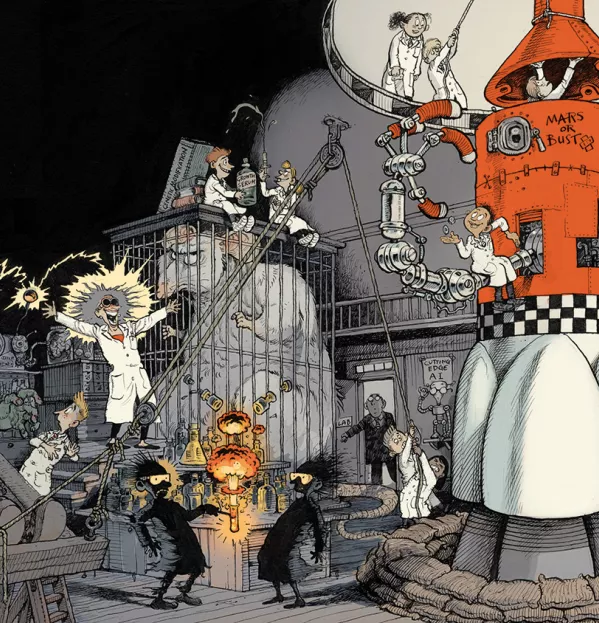

Too often I hear that this approach is unfeasible: modern science requires state-of-the-art labs and huge research collaborations. But this is wrong. There are numerous areas of work that can be developed in schools and do contribute to the science base. These research projects across science and engineering can be sustained over time and so be a more realistic immersion for both students and teacher-scientists than the one-off whizz-bang lecture.

Also, from the students’ point of view, if the teacher-scientist is helping them to attack problems for which the answers aren’t known, that can change both their understanding and perception of science. With so much evidence about the impact of the teacher determining engagement (eg, Exploring Young People’s Views on Science Education, Wellcome Trust, 2011), we need to be keener to facilitate the individuality and interest of the teacher.

In many of the current models of “outreach” and CPD, the potential of students and teachers isn’t realised. Not only can school students and their teachers contribute in research projects but also their flair and innovation can be released. So let’s make a semi-permeable membrane between schools, universities and industry in terms of recognising and valuing the output from schools and their teacher-scientists.

We can’t keep doing the same things and hope that miraculously we’ll increase the numbers of science, technology, engineering and maths teachers. Something has to change. Isn’t it time to make a more flexible profession where research and teaching can be combined and where entry into teaching doesn’t close off options in the subject you love.

We should want to retain and recruit more teachers to a profession where they both teach science and do science themselves - they are teacher-scientists. Establishing a richer connection between the world of science education and science research as a practical discipline could result in the recruitment and retention of more staff who value their subject passions and so inspire the next generation of scientists.

Becky Parker is director of the Institute for Research in Schools and a physics teacher

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters