Teachers will always fall short of perfection - and that’s OK

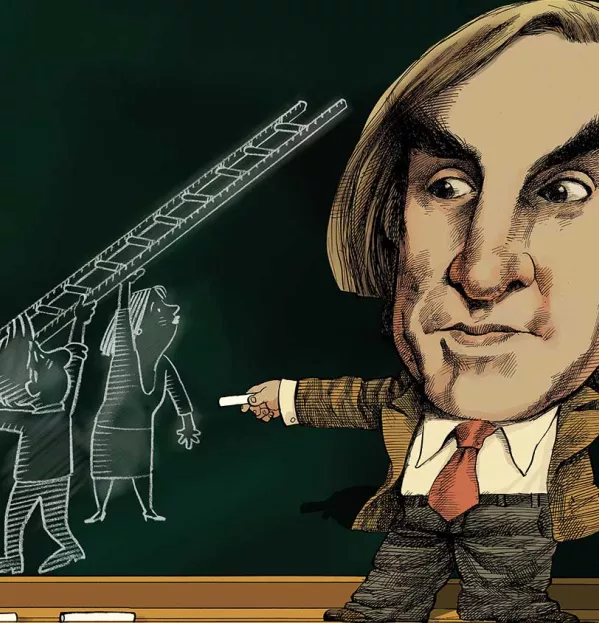

Now, more than ever, we must heed the words of Lawrence Stenhouse. His voice needs to be better known and his words better understood by the current generation of teachers, especially those interested in research. His work provides inspiration, insight and challenge.

Who was he? Stenhouse was one of the founding figures of modern educational research. Originally a secondary school teacher of English and history, and later a university teacher, he was the director of a major curriculum development project and latterly a professor of education at the University of East Anglia. He died in 1982 - mid intellectual career - but left behind a legacy of powerful ideas, of which “teacher as researcher” is only one.

The heart of teaching

At his most influential point, Lawrence lived and worked in a different era from ours. In the 1970s, there was no national curriculum, no national testing, no common leaving examination at age 16, no academies and no Ofsted. The system was not as well funded as now, education was not as well valued and, most significantly, schools and teachers were not subject to the degree of political control or influence that we currently experience.

So why should we want to ponder the thoughts of an educationalist from a different age? Because in my view, more than any other academic then or now, Stenhouse gets to the heart of the educational process, what it is to be a teacher, the “art” of teaching and the key to its improvement.

He begins one of his books by referring to an enduring fascination and frustration of the educational process: the inevitable gap between aspiration and reality. Nowhere is that clearer on a grand scale than in the disjunction between government policies on raising standards post-2010 and the results of national and international data. Each teacher also experiences it when trying to evaluate the effects of their teaching against their initial aspirations. We seldom achieve all we hoped for.

Stenhouse comments: “Our educational realities seldom conform to our educational intentions. We cannot put our policies into practice. We should not regard this as a failure peculiar to schools and teachers. We have only to look around us to confirm that it is part of the human lot. But … improvement is possible if we are secure enough to face and study the nature of our failures. The central problem of evidence-informed practice is the gap between our ideas and our aspirations, and our attempts to operationalise them.”

Elsewhere, he absolves us from guilt about not achieving perfection in our teaching by recognising the ultra-ambitious nature of the pursuit: “It is clear that the idea of education is sufficiently ambitious to preclude the possibility of perfect performances. No teaching is good enough: therefore good teaching is teaching towards the improvement of teaching. The implication is that all teaching ought to be seen as experimental.”

So much for those seeking consistently “outstanding” practice in their own teaching or that of the people they manage.

Stenhouse captures an essential characteristic of teaching - the pursuit of ideals by mere humans with weaknesses and shortcomings. He sympathises with our “lot”, but believes we can learn from falling short: “The gap between aspiration and teaching is a real and frustrating one. The gap can only be closed by adopting a research and development approach to one’s own teaching, whether alone or in a group of cooperating teachers.”

Research contributes to “the betterment of schools through the improvement of teaching and learning”, he says. “Its characteristic insistence is that ideas should encounter the discipline of practice and that practice should be encountered by ideas”. He argues: “The teacher research movement is an attack on the separation of theory and practice.”

Enquiry and experiment

Stenhouse is very clear that education is not an applied science concerned with establishing general laws of teaching and learning; the teacher is not an applied scientist, let alone a technician. “I am declaring teaching an art,” he says. “By ‘art’ I mean an exercise of skill expressive of meaning. Teaching is the art which expresses in a form accessible to learners an understanding of the nature of that which is to be learned. All good art is an enquiry and an experiment. It is by virtue of being an artist that the teacher is a researcher. The point appears difficult to grasp because we have been invaded by the idea that research is scientific and concerned with general laws.”

He would not recognise the contemporary claims about social science being the key - or even a key - to educational improvement or, for that matter, the aspirations of Ofsted that its findings should meet the social science criteria of reliability and validity.

As an art, teaching can never be perfected but it can be fostered and improved through aspirations translated into hypotheses that can then be tested and refined in the classroom. Teachers must be educated to develop their art, not to master it, for the claim to mastery merely signals the abandoning of aspiration. Contemporary notions of “master teachers” that appear with unnerving regularity would have no place in his more modest but more realistic view of what we can achieve.

For Stenhouse, the essence of teacher research and teacher development is sustained critical enquiry into your own teaching - not simply adopting procedures from competing alternatives, whether offered by government agencies, multi-academy trusts, neighbouring schools, local authorities, educational gurus or CPD providers. That enquiry should come from an anxiety to do better and be pursued not as a one-off but as an ongoing process, preferably with other interested teachers.

Stenhouse argues, perhaps with a little exaggeration, that “enquiry should, I think, be rooted in acutely felt anxiety, and research suffers when it is not. Such enquiry becomes systematic when it is structured over time by continuities lodged in the intellectual biography of the researcher and coordinated with the work of others.”

He would have been delighted to see teachers’ increased interest in research today but he would have warned about placing too much credence on their own or others’ findings.

Stenhouse is insistent on the provisional, tentative nature of all enquiries into teaching, whether by academic researchers or teachers themselves: “Findings must be so presented that a teacher is invited not to accept them but to test them by mounting a verification procedure in his own situation. Such proposals claim to be intelligent rather than correct.” He emphasises: “I am not seeking to claim that research should override your judgement; it should supplement it and enrich it.”

Current educational discussion is often fixated on “what works”. Stenhouse would have been less than enthusiastic. He wanted teachers to test out, and if necessary to adapt findings to the unique circumstances of their own classrooms. He would, for example, have been wary of any claims about inspection being authoritative and incontestable.

‘Lowering our sights’

Stenhouse was very aware of the difficulties facing teachers trying to research their own practice, including problems of time, access to research expertise and recognition of the importance of the activity by school and college leaders. However, the main barriers to teachers assuming the role of researchers in studying and improving their own teaching are social and psychological. The close examination of one’s professional performance is personally threatening; and the social climate in which teachers work generally offers little support to those who are disposed to face that threat. More than 30 years later, that “social climate” may well be changing; let’s hope so.

In truth, a piece such as this cannot do justice to the inspiration and insights of Stenhouse, but I encourage you to delve into his work.

As a great teacher himself, he was aware of the gap between his aspirations and practice but he was not discouraged - nor should we be. The last word goes to him: “But my practice is not successful. Success can be achieved only by lowering our sights. The future is more powerfully formed by our commitments to those enterprises we think it worth pursuing, even though we fall short of our aspirations.”

Colin Richards is a former primary teacher and university professor. He tweets @colinsparkbridg

Further reading

• Stenhouse, L (1975) An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development

• Rudduck, J and Hopkins, D, eds (1985) Research as a Basis for Teaching: readings from the work of Lawrence Stenhouse

• Stenhouse, L (1983) Authority, Education and Emancipation (All books published by Heinemann)

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters