Teaching loses its fear of Ofsted the bogeyman

It has long been seen as the teaching profession’s “bogeyman”, but new data obtained by TES suggests that Ofsted may be turning a corner in its relationship with heads and teachers.

The number of official complaints made about school inspections has fallen dramatically over the past three years - a period in which Ofsted purged hundreds of inspectors, overhauled its inspection framework and introduced short inspections for “good” schools.

Malcolm Trobe, interim general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said that the decrease in the number of complaints “ties in with everything that we are picking up”.

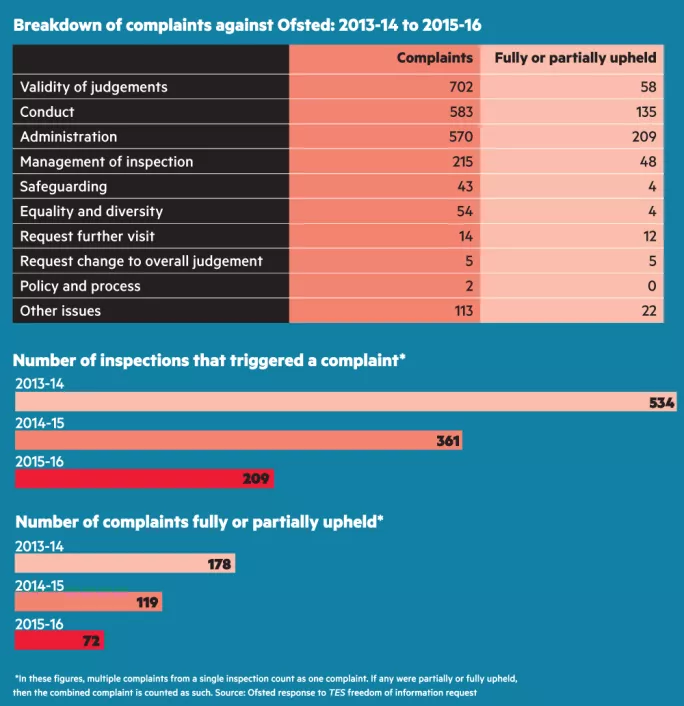

Data obtained by TES under the Freedom of Information Act shows that 209 school inspections resulted in a formal complaint in 2015-16, compared with 534 two years earlier - a 61 per cent drop. When the reduction in the number of school inspections over the same period is factored in, this represents a 25 per cent fall in the proportion that triggered a protest.

Sean Harford, Ofsted’s national director, education, described the drop in complaints as “gratifying”, but said that the inspectorate was not complacent.

Asked why fewer complaints were being made, he pointed to the change in the Ofsted workforce in 2015, when it removed 1,200 outsourced inspectors and brought its inspection team in-house.

“We have put a lot of effort into training inspectors directly. Previously, training was at arms-length for the additional inspectors. We now directly train them - we have put a lot of effort into making that sharper,” he told TES.

Mr Harford highlighted the slimmed-down guidance about inspections, and more open communication about Ofsted’s work, which has included mythbuster documents to reduce unnecessary workloads imposed on teachers to meet Ofsted’s supposed requirements. He has also used Twitter to respond directly to teachers’ concerns.

Growing confidence

Mr Trobe said that, while “all is not rosy in the garden”, the fall in the number of complaints tallied with his own experiences.

“There has been a significant decline, particularly since we had the inspectors brought in-house, in terms of issues coming up. Certainly, bringing everything in-house has led to what appears to be a more consistent approach in the first instance, and more confidence in the appropriateness of the judgement,” he said. “The clear message is that the position is significantly better than it was 18 months ago.”

However, Mr Trobe said that concerns remained about the short amount of time inspectors spent in schools, and their use of progress data in secondary schools.

A number of headteachers said that the 2015 reforms had increased confidence in the inspection process.

Dan Morrow, headteacher at Oasis Academy Skinner Street, in Gillingham, Kent, said that while in the past “Ofsted was the bogeyman”, Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMIs) now have a “moral purpose”. “They are the gatekeepers to the system. And that moral purpose therefore leads to incredible improvement, because they care deeply now about the how and the why, as well as the what,” he said.

‘I definitely felt the inspectors were thinking, “We’re here to help you”’

“Dealing with the why is really important when you’re in schools in deprived circumstances. It shows a collegiate approach, unlike the old system. It includes, rather than excludes, schools.”

Andrew Day, executive director of the Northumberland Church of England Academy, described inspections as “much more rigorous”, but said they were still too narrowly focused on outcomes.

“The fact that they’re in-house means that you’re a little bit more certain that the people who are doing the inspections have been trained well. And they’re a little more consistent in their approach”, he added.

Michael Dillon, headteacher at Birch Hill Primary School, in Bracknell, Berkshire said that he had been inspected twice as a leader, most recently in March 2015. He said: “The last time was in 2011, under the previous framework. Both were difficult but good.

“The second inspection, I definitely felt the inspectors were more, ‘We’re here to help you; we want the right outcome for your school.’ It felt like the tone was a little bit more collaborative. But it was still difficult, and challenging, and hard.”

Questions of judgement

Ofsted judgements were the biggest cause for complaint in each of the past three years, raised 702 times in total, and mentioned in almost two-thirds (64 per cent) of complaints about inspections.

However, although judgements were the biggest source of complaints, these complaints were also among those least likely to succeed, with just 8 per cent fully or partially upheld.

“It’s understandable why people complain if they don’t like the judgement, but the systems built around it are such that we can have relatively good confidence in the judgement that comes out,” Mr Harford said.

The next most common causes of concern between 2013-14 and 2015-16 were the conduct of an inspection (583 complaints) and administration (570 complaints).

Mr Harford added that Ofsted may examine the variation in the number of complaints about school inspections in different parts of the country.

The South East of England saw the largest number of formal complaints in each of the past three years - with its total of 202 more than double the 91 made in the East Midlands, which had the fewest complaints.

Mr Harford said: “It’s fair to say we get more complaints from the South East and London region in total. That could be due to the difference in the number of inspections and the split of inspection judgements awarded.

“I don’t think there is any particular systemic issue around it, but it might warrant a bit of a further look.”

Although there was significant geographical variation in the number of complaints against inspections, the proportion upheld was more consistent, ranging from 30 per cent to 39 per cent across the eight Ofsted regions over the past three years.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters