Whenever I find myself doing something fun, I feel oddly guilty. But I take comfort in the fact that inspiration for research emerges from the most unusual places.

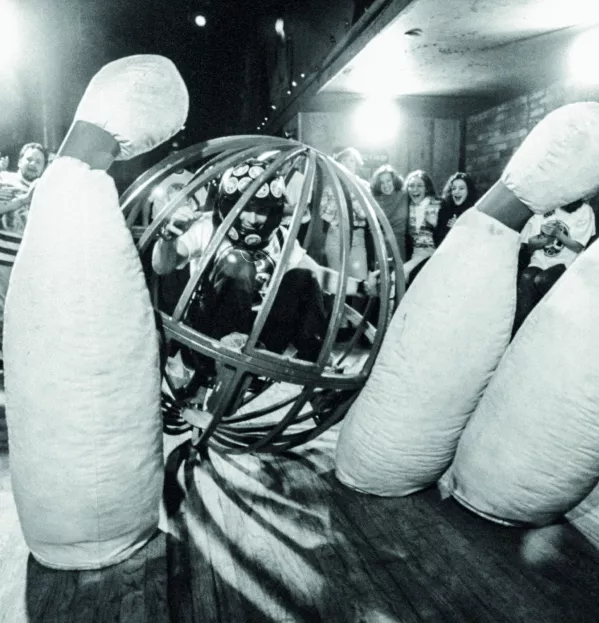

Take ten-pin bowling, for instance. As a beginner, you aim for the pin in the middle, hoping to knock down as many as you can. The problem is, though, that in doing so, you risk leaving the last two pins at the back standing on each side. Professionals call this the 7-10 split, and it’s virtually impossible to get these two pins with one bowling ball.

To avoid this, professional bowlers throw the ball down the aisle with a curve, skilfully spinning it into what they call the right pocket (or left pocket if you are left-handed). This offers a much better chance of a strike but it is a much harder bowl to get right.

Canadian researcher Shelley Moore observed this and saw in it a powerful analogy for the classroom. When we aim for the student at the “front” (the average student), we end up missing those at the “back” (those who need additional support). But if we change how we plan, teach and assess, with the question, “Which of my pupils are getting stuck and what do I need to do so they get it?” (Moore, 2015), we stand a better chance of helping all of our students succeed.

This chimes with the work of Florian and Black (2011). They describe the dangers of directing teaching at the needs of the majority of pupils and then doing something very different for those with exceptional needs - the very high or low attainers.

Avoiding this raises a challenge for inclusion around the language we use, where labelling (high attainer, low attainer) and modelling (“those are the five special educational needs and disability kids in my class” ) divide pupils from their classroom peers and reinforce a culture of lower expectation from teacher and pupil alike. Of course, the descriptors of, say, autism or dyslexia are unavoidable and are helpful - but only if they are a starting point for pedagogy.

The message from this research is that we should focus on inclusive pedagogy that considers a class as individuals, not one unit or as a series of labels, and to aim our teaching at those who will struggle most. It is an approach that rejects labelling by ability and, informed by the work of Susan Hart et al (2004), urges teachers to create environments that do not limit the expectations of the teacher or the pupils.

This doesn’t happen enough. Teachers need more help to understand inclusive teaching. There is a gap in what we understand about inclusivity in theory and what we see day to day in our classrooms.

We need to do more work in applying theory to practice and we need to look at our classrooms differently. Like the professional bowler, we need to practise our aim for the hardest targets.

Margaret Mulholland is the special educational needs and inclusion specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders

This article originally appeared in the 27 March 2020 issue under the headline “Want to reach your high and low attainers? Throw a curve ball”