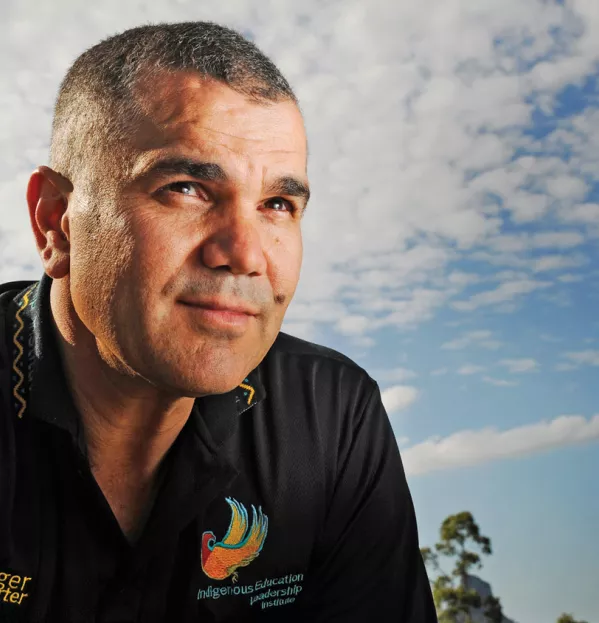

TES talks to...Chris Sarra

Where there is complexity, there is opportunity,” says Chris Sarra, founder of Australia’s Stronger Smarter Institute.

It’s a statement that he has been trying to get school leaders and teachers to buy into for more than 10 years. He set up the institute in 2005 to tackle the underperformance of indigenous and Torres Strait Island students in Australian schools. He believes that the underperformance was caused by low expectations and poor understanding of how to motivate these children.

It’s a persistent problem. According to statistics released by the Australian government, the overall school attendance rate for indigenous students was 83.7 per cent, compared with 93.1 per cent for non-indigenous students. In 2012-13, only 58.5 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island students were finishing Year 12.

‘I had been sold short by teachers who didn’t push me because I was Aboriginal’

These children have the same problems you see with other marginalised or disadvantaged groups in countries around the world, he says. “As educators we will sometimes write kids off because of where they come from and the complexity of their home life,” he explains. “That’s as true in Australia as it is in the hardcore parts of London, places throughout the US and, indeed, throughout the world.”

Sarra was formally a headteacher at an Australian state school before setting up the institute. Of Aboriginal heritage himself, he set about changing the cultural conditions for indigenous students in his school and continued that work with the institute.

He explains that with those students that have a hard time away from school, for whatever reason, and who then become disengaged, the school needs to compensate. It can do that by shifting the focus from the problem to the solution.

“It’s about building up a positive sense of identity, embracing positive community leadership and building a culture of high-expectations relationships,” he says. “We as a profession have to be able to shift from having to explain why kids were being disengaged to a point where we are saying we can do this and get them engaged.”

Schools need to compensate

The Stronger Smarter Institute runs courses for teachers to help change their expectations of indigenous students. The programme has helped more than 2,500 school and community leaders, in turn impacting 38,000 indigenous students.

The key, he believes, to the success, is a “no-excuses” strategy familiar to many in the UK education system - a belief that a less-than-ideal home life should not be a reason to have low expectations of a child.

“I used to get fed up with people blaming the complexity of the community as to why they couldn’t make a difference.

“One principal was telling me about how they couldn’t make a difference because of the drinking, the fighting and the sexual abuse in the community.

“My response was: ‘It’s clear to me that kids are making a choice to locate themselves among the drinking, gambling, fighting and sexual abuse rather than come to your school. We need to offer something better.’”

The courses, first and foremost, teach a change in attitude. Similar to the unconscious bias training the US police force is undergoing currently, the Stronger Smarter Institute forces teachers to recognise their habitual patterns and the impact that can have on how they form relationships with students depending on their social circumstances. It persuades teachers that high expectations for all - regardless of background - is the key to success for all, rather than modified expectations as a compensation for a less-than-ideal home life.

“It’s about connecting with the core humanity of the kids and parents, and understanding it at that much deeper level - they have a right to a good quality education and they have a right to turn up to a school where they can have a sense of hope nurtured for them,” he explains.

Sarra was inspired to do this by his own experiences in the education system. Although he did not achieve the required academic results, he was able to get on to a teaching course at the Brisbane College of Advanced Education owing to a programme aimed at getting more indigenous teachers into the classroom.

He was told he could spread the three-year course over four years, starting on a 60 per cent workload. “[But] I realised in the first year that I could do this. I had been sold short by teachers who maybe didn’t push me as hard because I was an Aboriginal student or didn’t believe in me, just because I was Aboriginal,” he says.

Mentored by his new teachers, Sarra then chose to increase his workload over the next two years to finish the course within three years.

Since then his mission has been to ensure that disadvantaged children do not have the same experience he did of low expectation leading to low achievement. He says that teachers across the world owe it to these children not to let an inbuilt and inaccurate view of what they can achieve get in the way of their education.

“Of course, it’s nice working with middle-class kids and the only decision they have to make is, ‘Do I have Nutri-Grain or muesli for breakfast’ - of course that’s easier,” he says.

Teaching is the “greatest profession in the world”, he continues. But if we are going to be in that profession then we owe it to children “to continually offer and nurture a sense of hope” among them all.

He recognises that shifting mindsets in this way is going to be a long process. But he is committed to challenging perceptions, teacher by teacher, until things change. “We are content just to keep chipping away,” he says, “until we get to that tipping point.”

Brittany Vonow is a freelance writer based in London. She tweets at @bvonow

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters