UK leads the way in creating the scientists of the future

The UK is one of just a handful of countries where teenagers do well at science, enjoy it and want to become scientists, international research revealed this week.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) results published on Tuesday delivered mixed news for the UK, revealing that although pupils’ scores had dropped in science, the country had managed to climb six places up the ranking to 15th place.

Other significant findings for England in the Pisa report included the fact that almost half of 15-year-olds were taught in schools where the head was concerned about teacher shortages.

The study also recommends a reduction in academic selection within schools. It warns that there is more going on in England’s classrooms - through setting and streaming - than anywhere else in the world, with 91.3 per cent of 15-year-olds taught in ability groups.

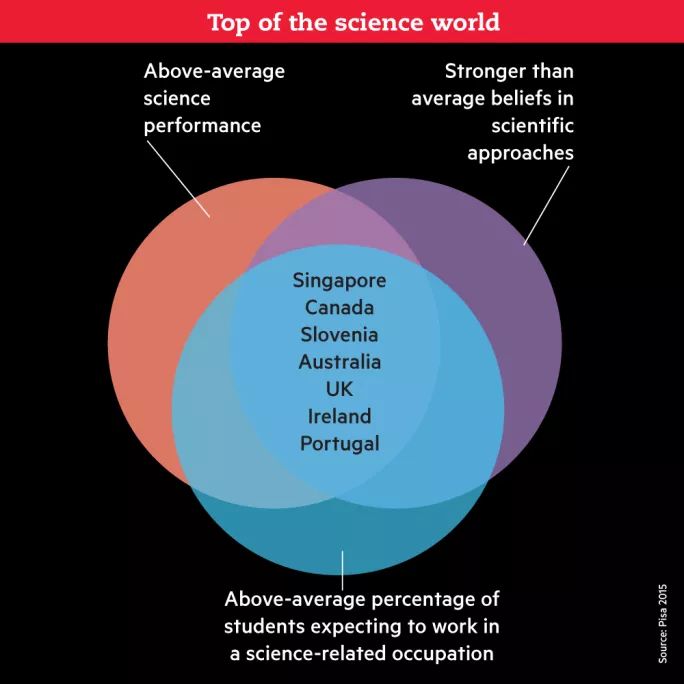

Andreas Schleicher, director for education and skills at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which produces Pisa, revealed that the UK was among only seven countries where pupils had above-average science performance and stronger than average beliefs in scientific approaches, and where an above-average percentage of pupils expected to go on to work in a science-related occupation.

It is about engaging students and making science relevant

The other countries were Singapore, Canada, Slovenia, Australia, Ireland and Portugal. Other high-performing countries, such as South Korea and China, had students who did well in science but who were not interested in becoming scientists, Mr Schleicher said. In the US, many students wanted to become scientists “but lack the knowledge and skills to live up to their dreams”, he added.

Mr Schleicher said that having both a scientific attitude to knowledge and an enjoyment of science was the link between students doing well at science in school and wanting to make it a career.

“It is not about success on a science test,” he said. “It is about engaging students and making science relevant. It is making them think like a scientist - that is the key to success.”

Pisa also says that one way to help students do better in science is to reduce selection.

‘It’s not Harry Potter’

Angel Gurría, secretary-general of the OECD, speaking at the launch of the report in London, drew parallels with the “sorting hat” in the Harry Potter books; the magical entity that decides which house pupils go into when they arrive at Hogwarts school.

“An early sorting may be appropriate for students of magic, but it doesn’t work in the real world,” he said.

He issued the warning as ministers in England consult on an expansion of selective grammar schools. School standards minister Nick Gibb said that the Pisa findings could provide a “useful insight” into how to harness the expertise of selective schools.

“We know that grammar schools provide a good education for their disadvantaged pupils,” he said. But the government’s own briefing note on Pisa, written by John Jerrim and Nikki Shure, of UCL Institute of Education, said that while one argument often made in favour of selective school systems is that they may help disadvantaged young people to excel academically “evidence from Pisa, however, provides little support for the notion that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to succeed… Rather if anything, the opposite may hold true”.

There is a lot of separation of students that happens within schools

Mr Schleicher also pointed out that there was more selection going on within schools in England than in any other country that Pisa had data for. “Looking at grammar schools is surface of the issue,” he said. “There is a lot of separation of students that happens within schools between classes.” In addition, Pisa warns about teacher shortages in England after finding that 45 per cent of pupils were taught in schools where the headteacher felt that teaching was hindered by the problem. This was well above the OECD average of 30 per cent.

Some 22 per cent of students in England were taught in schools where headteachers were concerned that inadequate or poorly qualified teaching staff were hampering progress. “Schools facing cuts have the worst of all worlds,” said Mary Bousted, the general secretary of the ATL teaching union. “There is a toxic mix of issues creating a crisis in teacher supply. I am not surprised that 45 per cent of our school leaders say it is a key thing that is holding them back.”

Malcolm Trobe, interim general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, shared such concerns about teacher supply. “There has been a major problem for the last three years and it has been getting worse. From what we hear from members around the country, the situation is extremely serious,” he said.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “Figures published recently show teaching continues to be an attractive career…But we recognise that there are challenges, which is why we are spending more than £1.3 billion over this Parliament.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters