My father was Jamaican and, like many, I take great pride in the feats of sprinter Usain Bolt, the fastest man in the world and a global star. Sadly, for those of Caribbean heritage living in the UK, such success has been hard to come by - especially educational success.

Imagine you were a black Caribbean young person. If you sat your GCSEs in 2008, you were part of an ethnic group that achieved, on average, the lowest results of all groups. And at the end of the sixth-form phase, your average point score was the lowest.

The good news is that since 2008 you would have pulled ahead of white British pupils in one important respect: black students (Caribbean and African) are now 9 per cent more likely to go to university. Positive, yes, but other groups are doing even better than that: Asian pupils are 14 per cent more likely; for Chinese pupils, it’s nearly 30 per cent.

Despite the increase in the number going to university, the picture changes if you look at the more selective universities. While Chinese and Asian applicants are more likely than white British students to go to a high-tariff university, black students are about 30 per cent less likely than white students to do so.

In 2011-12, black students made up 2.7 per cent of those at Russell Group universities. The entry rate for black students to high-tariff universities has now risen to 6 per cent, but this is still the lowest rate for all ethnic groups.

Only a small proportion of black students do the traditional A-level subjects favoured by Russell Group universities, and therefore few get into prestigious universities and progress into high-earning careers.

And this is where the further education sector is so critically important for the success of BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities, still battling to overcome longstanding obstacles to social mobility. The school system is working better for young people from BAME backgrounds up to GCSE level, but is still producing unimpressive results post-16. This means that many come to FE colleges to reboot their academic prospects.

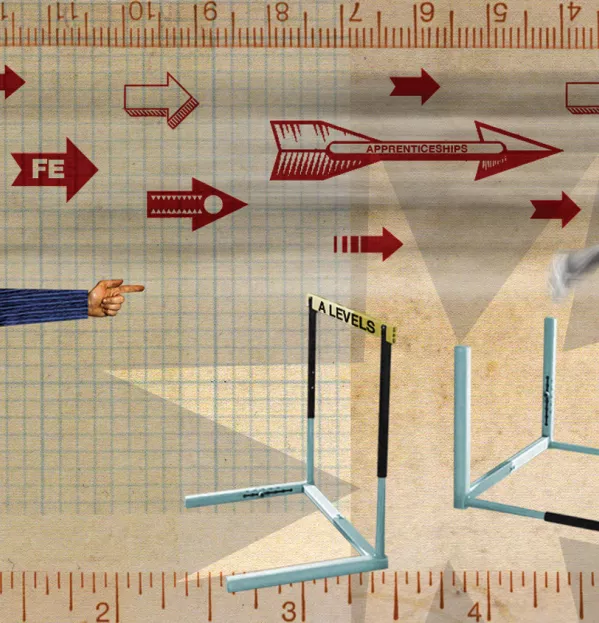

So FE colleges need to have the barriers faced by BAME students high on their agendas and work with students to explore alternative pathways to success. To do this, they need to have a workforce that reflects ethnic diversity. FE urgently needs to up its game.

Meanwhile, the wait for a Usain Bolt of academic achievement to come flying through the British education system goes on. Will they leap over the hurdles of A levels and Oxbridge? Or will they come sprinting around them via FE and apprenticeships?

Andy Forbes is principal of the College of Haringey, Enfield and North East London