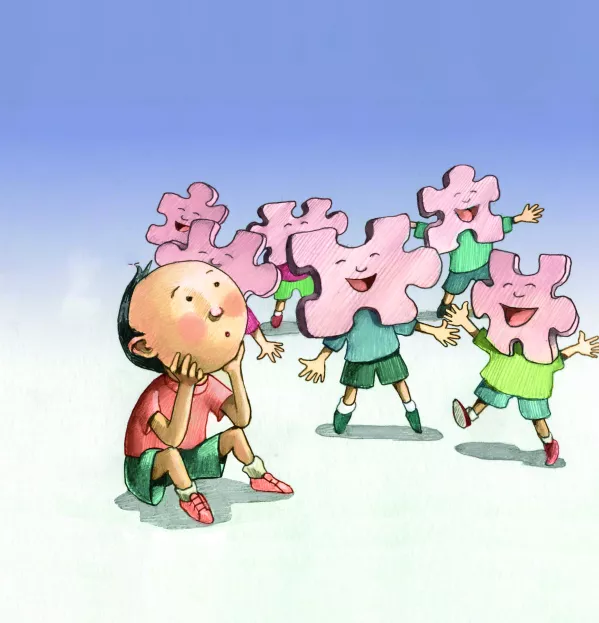

What do you include in inclusion?

I have a confession to make. Despite working in inclusion for years, it’s surprisingly easy for me to still fall into the trap of assuming that people know what I mean when I talk about it. That’s confirmation and proximity biases for you.

It’s important for me to recognise this because inclusion is a slippery term. At a CPD session for headteachers recently, it struck me how many different interpretations of the word “inclusion” there are, and how that can have an impact on how schools lead on the issue.

We asked the heads what inclusion means and what other words explain the concept of inclusivity. The variation in responses was huge, and one head summed up the problem succinctly: “Many of us are working on a much more rudimentary definition, considering integration of pupils with special needs, rather than a much broader definition of diversity and everyone being different, which the Sendcos in the room seem much clearer about. It has made me realise that I could have 80 different perceptions of what we mean when we regularly talk of ‘inclusivity’ as a staff body.”

So, what do we do about this problem?

In 2017, Unesco developed a guide to ensuring inclusion and equity in education with the central premise that every learner matters and matters equally. In my view, that’s a strong working definition for schools.

How do we get there? The good news is that no leader or teacher disagrees with the principles of inclusion - we are preaching to the converted.

However, there are systemic issues that limit our ability to be inclusive. Numerous studies (Unesco, 2009; Wilkinson and Pickett, 2010; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2012) show the benefits of inclusivity on achievement and national standards. Yet we continue to contend with a system that encourages forms of student segregation through policy and funding that identifies one group of pupil characteristics above or beyond another.

While we may not be able to overcome those systemic challenges at a school level, there is good evidence that how a leader defines and enacts inclusion does matter.

A University of Helsinki study looking at the difference between the rhetoric and the practice of inclusion in Alberta and Finland recognised that leaders were pivotal to the degree of inclusivity demonstrated by a school. If inclusion was poorly defined within the schools and for the principals, it was usually just the physical integration of pupils that preoccupied their ambitions. The researchers made a clear recommendation that leadership training programmes should contain more broad and central issues related to the practice of inclusivity within school development planning (Lynch, 2012).

So what should leaders be doing, in practice?

A study from Australia concludes that leaders need to reinforce inclusive practices. They can do this through frequently articulated expectations, support and the acknowledgement that, for all stakeholders, inclusion is a constant journey toward a shared vision.

In addition, during a time of high anxiety around school closures, the Education Endowment Foundation published new guidance for supporting special educational needs and disability in mainstream schools. The five-point summary is clear:

- Create a positive and supportive environment for all pupils, without exception.

- Build an ongoing, holistic understanding of your pupils and their needs.

- Ensure that all pupils have access to high-quality teaching.

- Complement high-quality teaching with carefully selected small-group and one-to-one interventions.

- Work effectively with teaching assistants.

The key point is that inclusive leadership is about seeking out and listening to varied voices, valuing expert knowledge and enabling staff to work in partnership within shared leadership structures that are designed to make inclusion work at every level.

Margaret Mulholland is the special educational needs and inclusion specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders

This article originally appeared in the 24 April 2020 issue

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters