What is emotion’s role in cognition?

Alistair doesn’t get it. And what’s worrying you is, you don’t get why Alistair doesn’t get it.

You’ve applied every tactic from your pedagogic toolbox. You have merged your experience with research from cognitive science. You’ve spaced the content, taking every precaution to ensure you address the limitations of working memory. What is the vital component you haven’t factored in?

Perhaps it’s the very same component that unduly influences cognitive psychology in the laboratory? That annoying human mental state that has the power to disrupt all your hard work, reduce the efficiency of cognitive resources and limit some students’ ability to recall the information?

Perhaps what you’ve overlooked is emotion. For while we may discuss at length the role of anxiety, and its links with mental health and wellbeing, other facets of emotion remain all but absent from the education conversation.

Which is odd, if you consider that the research is clear that emotions have an important role to play in processes such as attention, memory and decision-making, and that they are also linked to other factors such as motivation.

In a recent interview with Tes, John Dunlosky, a cognitive psychologist at Kent State University in the United States, suggested that factors such as emotions and motivation “have to play a part in learning”. Meanwhile, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Antonio Damasio of the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California put the case for emotion in learning a little more forcefully, insisting that “any competent teacher recognises that emotions and feelings affect students’ performance and learning”.

They add: “Educators often fail to consider that the high levels of cognitive skills taught in schools (including reasoning and decision-making, language, reading and mathematics) do not function as rational disembodied systems, influenced but detached from emotion and the body” (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007).

The vast majority of emotion research has focused on the role of fear and anxiety. For example, Nick Berggren discovered that trait anxiety places greater pressure on cognitive load, thus reducing the ability to focus on the task in hand (Berggren, Richards, Taylor et al, 2013). And Amitash Ojha found that negative emotions increase cognitive load of individuals with lower levels of intelligence but have no impact on those of average intelligence (Ojha, Ervas and Gola, 2017).

Meanwhile, incorporating emotion-laden stimuli (both positive and negative) with to-be-remembered information has been found to enhance recall, while inducing low moods can inhibit it (see Smith, 2018 for a more comprehensive discussion).

Other research studies into emotion have investigated the relationship between boredom and curiosity (Mann and Cadman, 2014) and the role of benign envy on motivation (Lange and Crusius, 2015).

But, despite this impressive research base, education - and, particularly, much cognitive psychology research - continues to treat emotion as having little relationship to cognition. The question is: why?

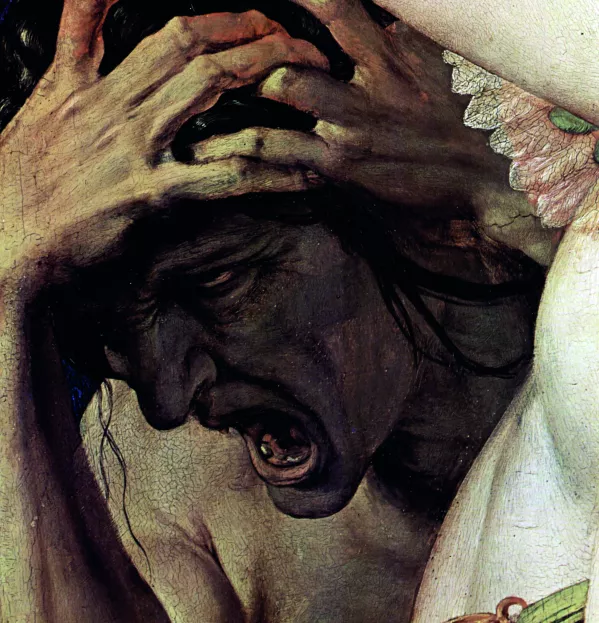

A toddler in a china shop

Traditionally, emotion and cognition have been treated as separate processes. Even more detrimentally perhaps, emotions have been viewed only as a distraction, an extraneous variable with the power to disrupt even the most carefully controlled experiment.

Immordino-Yang and Damasio liken this view of emotions to a toddler in a china shop, interfering with the orderly rows of shelves. Many researchers, therefore, have tended to control for emotions rather than accept their role in learning and achievement - they stick emotions in reins and try to forget about them.

In schools, it is easy for us to think this way, too: our power to influence emotion, we may think, is limited, so just focus on the learning.

But this is just one of many reasons emotions are often left out. For example, many of the problems with emotions arise because it’s not always clear exactly what emotions are or how they can be studied. As Dunlosky points out: “Until we understand it, we cannot control for it.”

However, some have had success in trying to pin them down. Antonio Damasio proposes a neurological definition of emotion as “complex programs of acting triggered by the presence of certain neural systems” (Damasio, 2011), while many psychologists view them as three interrelated constructs: affective tendencies, core affect and emotional experience.

The most relevant of these three constructs to teachers is core affect, the way we feel at any particular time. Core affect is also generally quite straightforward to measure through self-completion questionnaires, where individuals are asked to rate a feeling in terms of valence (a continuum ranging from pleasant to unpleasant) and arousal, or our bodily activation (such as heart rate) ranging from low to high. So, if a student were asked to rate their levels of anxiety just before an exam, they might rate valence as unpleasant but arousal as high. What we think of as positive emotions, therefore, will have positive valence, while negative emotions will be closer to the unpleasant end of the scale.

So we do have some idea of what emotions are and a way of measuring them. But emotions are tricky. If we are smiling or laughing, chances are that we are happy, while if our mouth is turned down or we are crying, we’re probably sad. The problem is that many people laugh when they are nervous and cry when they are happy, so it would appear that we don’t all react in a uniform way to the same emotion.

Furthermore, emotions are also, to an extent, dependent upon the language with which we use to name them. For example, sometimes we might feel happy, yet that happiness is tinged with melancholy. We might say we are ambivalent, but that still doesn’t really describe how we feel. The Chinese language has at its disposal bēi xi jiāo jí, meaning intermingled feelings of sadness and joy, a much better description than ambivalence.

And we don’t really know how many emotions there are. Anger, sadness and happiness might be obvious, but what about curiosity, interest or boredom? As far as research is concerned, there is no real consensus.

Going through the emotions

Where there is some agreement is that there are either six or eight pure emotions - anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise (and perhaps joy and anticipation) - with all other emotions being elements of these. American psychologist Robert Plutchik proposes that basic emotions can be blended, much in the same way we can blend colours, to produce many more (Plutchik, 2001).

I imagine you are beginning to see how messy emotions can be. That’s before we have even got to the point of discussing whether emotions are good or bad. Is anxiety, for example, always a bad thing? Anxiety and fear certainly serve a useful evolutionary purpose; it’s unlikely our distant ancestors would have lasted very long if they weren’t afraid of that rapidly approaching sabre-toothed tiger. Anxiety increases arousal, preparing our body for fight or flight, a vital survival instinct.

But the fight-or-flight response is designed to be short-lived and once the danger has passed our body returns to its default position. If the anxiety is prolonged (such as in the case of chronic anxiety disorders), we remain in an overly alert state, which in turn negatively impacts a number of bodily systems, including cognition and the immune system.

The same is true for all emotions; that is, they are neither intrinsically positive nor negative. Psychologist Reinhard Pekrun uses the terms “activating” and “deactivating” emotions rather than positive and negative. Emotions serve a purpose, but only if they occur under the right circumstances (Pekrun, 2006).

Boredom, for example, might lead us to shift our attention away from the task in hand, but it might also result in increased creativity or motivate us to find something else to do. Similarly, curiosity can supercharge the desire to learn, but we all know what it did to that poor cat.

Where does all this leave teachers? Perhaps in light of all of this complexity, ignoring emotions in research and in the classroom seems sensible. In our example at the beginning, the reason Alistair doesn’t get it may well be down to emotion, but a teacher’s ability to unpick that is arguably minimal and the cost of trying disproportionate.

However, if we think of education as a means by which children and young people can build repertoires of cognitive and behavioural strategies and options, acknowledging the interplay between cognition and emotion actually allows teachers to recognise the complexities of situations and respond appropriately and flexibly. In short, giving more consideration to emotion can be useful.

Perhaps one of the most obvious emotions to impact on behaviour is anxiety. Anxiety is a complex state and can manifest in curious ways, from withdrawal to aggression. While incidents of aggression should never be excused, it can be worth asking if the behaviour is the result of anxiety and, if so, how the teacher can help the student alter their response to it.

As for learning, behaviours such as procrastination or the continued insistence that a task is too difficult can arise from a number of emotions thought of as deactivating. If we consider behaviour to be goal-driven, then any circumstance that blocks our path towards our goal will trigger an emotional response. Helping students to cope with these setbacks mitigates the influence of the emotion.

For example, if a pupil’s goal is to achieve a higher grade on a test than their previous grade, failing to achieve this might result in feelings of guilt or shame at having been unable to reach their goal. These emotions, in turn, can result in the student abandoning any future goal. However, by encouraging pupils to anticipate and plan for setbacks, we encourage better emotion regulation and promote academic buoyancy.

Does not compute

Admittedly, some emotions are trickier to deal with. Boredom, for example, is an inevitable part of life and there will always be times when learning is less than stimulating. In some circumstances, posing interesting questions can spark curiosity (another emotional state), while at other times, emphasising the need to complete boring tasks to reach longer-term goals can be enough to motivate.

Take, for example, learning to play the guitar. The process of learning chords and chord transitions can be painfully boring, yet by emphasising the end result (being able to play a particular piece of music or jam with friends) can spur us on.

But how does this fit with other cognitive psychology research? Emphasising the role of emotion in no way diminishes the usefulness of cognitive science, but it can help us understand its limitations. For example, cognitive psychology research can lead us to view our minds as computers; emotion can correct that misunderstanding.

Indeed, Ulric Neisser, widely considered to be the founder of the cognitive approach, was highly sceptical about the computer metaphor’s ability to explain specific aspects of human behaviour, including emotions. Unlike people, “artificially intelligent programs tend to be simple minded, undistractable and unemotional,” he wrote in his seminal 1967 book Cognitive Psychology. Neisser also insisted that the body provides important additional sensory experiences, implying that cognition is not confined to the brain.

More recently, neuroscientists have found that multiple areas of the brain are involved in the simplest and most mundane memory tasks, and when we add strong emotions to the mix, millions of neurons became more active (Palombo et al, 2016). For example, when people recall past events, neural activity increases in the amygdala, medial temporal lobe, anterior and posterior midline and the visual cortex. These areas are involved in a number of functions, from emotional activation to literally seeing the experience in our mind’s eye. The amygdala, for example, plays a major role in memory, decision-making and emotional response. Cognition and emotion are, therefore, working together.

So yes, do be influenced by cognitive psychology but acknowledge, too, that emotions are an important part of the cognitive process (and, therefore, learning). Rather than being the toddler in the china shop, Immordino-Yang and Damasio insist that we should see emotions as the shelves underlying the glassware because, without them, cognition has less support. Only when teachers place emotions on an equal footing with cognition will it become apparent that both are working together to support learning or to hold students back.

Marc Smith is a chartered psychologist and teacher. He is the author of The Emotional Learner and co-wrote Psychology in the Classroom. He tweets @marcxsmith

This article originally appeared in the 26 July 2019 issue under the headline “Don’t fight the feelings”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters