Why risk-averse success rates breed failure in colleges

In December, the highly respected research organisation Education Datalab produced a report suggesting post-16 outcomes are worse in areas with colleges and without school sixth forms. Given the generally poor quality of guidance in schools, and our ability as colleges to put students on the most appropriate programmes, this felt wrong. But the credentials of the report’s authors are impeccable, so we need to take it seriously.

Clearly, there are some inherent issues with how these things are measured. The nature of our courses means even the brightest academic students at 16 begin some vocational programmes at level 2. Nevertheless, the report speaks to a lurking fear I have that, as a sector, we are nowhere near ambitious enough for our students.

On the face of it, my fears should be groundless. The most recent performance tables show the average student achieves distinction level. Are we lauded for such astonishing attainment? No. As Tes reported last month (bit.ly/SystemReview), we hear calls to review the external verification system (code for grade-inflation concerns) and Lord Sainsbury is drafted in to review our curriculum.

The root of the problem is surely the fear of failure and an obsession with success - or more specifically, achievement rates. By definition, if you push people harder to achieve the possible, the unlikely, the improbable, perhaps even the near-impossible, some aren’t going to make it.

Paradox of achievement

Surely being ambitious for our students and our community means accepting that?

Newcastle United are winning most of their games in the Championship. When they win far fewer in the Premier League next year, fans and pundits will not say they are a worse team. Too many of our incentives and punishments encourage us to settle for doing well at the lower levels and this needs to change.

Ofsted would say it is focused on ambition with a framework that references added value and progression, but its documents on how data is used refer first to achievement rates in any list of evidence used. Guidance on judging outcomes explicitly states that low achievement is inadequate. To be judged outstanding, achievement must be very high or rapidly improving.

Paradoxically the fear factor has become more acute as colleges get better. The difference in achievement rates between a lower-quartile and an upper-quartile college is about 6 per cent. Colleges are now bunched into a huge peloton. In a typical FE class of 16, one extra student passing or failing can lead to you either taking the yellow jersey or falling off the pack. In such a climate, why take a risk?

My college is currently engaged in the area review process. The data produced at the meetings highlights the negative impact of this lack of ambition. While all colleges in our patch have very similar achievement rates and serve similar towns with similarly poor school results, there is huge variation in the proportion of young people and apprentices studying at levels 3 and 4.

I am particularly proud that my college serves an area with below-average results in schools at age 16 but above-average results for young people achieving full level 3 qualifications at age 19. That recovery is our achievement. It has been a deliberate policy of our college to have long programmes that cover more than one level of study.

When employers and the country need our students to have advanced and higher levels of skill, we should not be allowing students to leave before they’ve achieved them.

We have moved our curriculum centre of gravity upwards without changing entry criteria, so that 63 per cent of young people are studying at level 3. Most others in our region show figures below 50 per cent.

When 60 per cent of young people come out of school at 16 with level 2 and fewer than 10 per cent perform below level 1, we should be able to get most students to level 3 by the age of 19.

Kick out level 1

It also begs the question: why is there so much level 1 provision in colleges? There is no case for such a thing as a level 1 programme of study. As a minimum, surely almost all students should be on level 2 programmes, even if they are elongated.

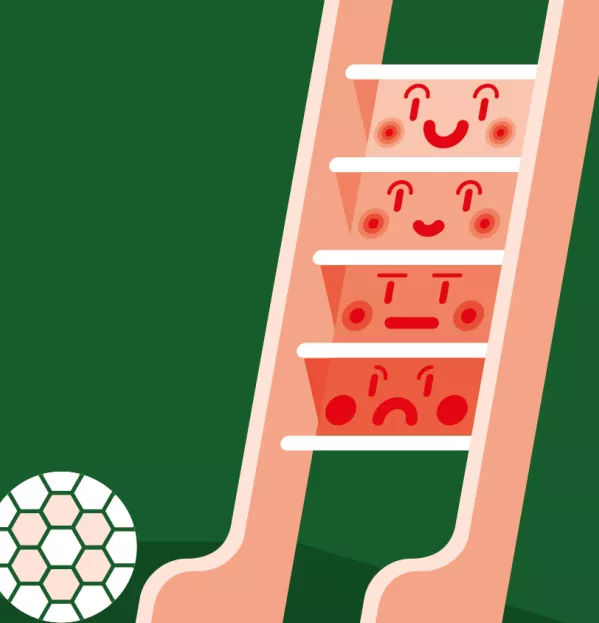

Level is also more important than subject. Our internal data is clear that progression means employment. Some 40 per cent of students who choose to leave our college with only a level 1 qualification end up unemployed. That figure falls to 15 per cent for those who leave after level 2; 7 per cent if they leave after level 3; and 2 per cent of those who complete level 4.

Colleges should be the engines that deliver large numbers of highly skilled individuals. Focusing on achievement percentages is unhelpful, a poor performance measure.

It would be much better to judge colleges by the proportion of activity at advanced level and the absolute number of students produced with advanced-level qualifications. This would encourage risk and progression. Maybe we should classify every student who leaves after level 2 as having failed level 3. That would bring achievement rates down sharply from 83 per cent to something like 50 per cent, with much less bunching.

We need to be more courageous and get more students playing in the Premier League, even if some end up relegated.

Ian Pryce is principal of Bedford College. He tweets as @ipryce

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters