Why you should ditch the canon

Literary texts are relatively static objects. Regardless of which shelf in the world they’re on, versions of the same work will tend to contain the same words in the same order. Of course, there are some minor differences - alternative covers, new editions, introductions and so on - but, in a broad sense, the fact rings true for all texts, whether they are by William Shakespeare, John Green, Charles Dickens or JK Rowling.

Readings, however, are not static, because reading involves not just the text but also the reader, and readers are different from one another. Readers bring different knowledge, experiences and tastes with them, which form an inextricable and fundamental part of their interaction with any text they encounter.

There are often common threads and broad agreements between readers, but our own interpretations, responses and evaluations are still unique to us: they are different because we are different.

Dynamic process

Equally, the same person’s reading of a text will change over time because reading is a dynamic and interactive process.

The knowledge and experiences we bring to and have foregrounded in our minds vary and change, too. These are the central principles of how reading and the mind interact, and they raise important questions about why and how we read fiction with young people in school.

The knowledge and experience a person brings to the act of reading is often termed their “schematic knowledge”. A schema is, in essence, an individual’s dynamic understanding of a concept, object, event, person, place or thing. The schemas students bring to a lesson are relevant considerations across school subjects - their understanding of gravity before a science lesson is a schema they will consciously and unconsciously draw on in the same way that they bring their existing knowledge of texts, genres, and themes to their reading of a novel or poem in English. Regardless of the topic, the interaction of background knowledge with new information is how humans make sense of and negotiate new knowledge and experiences: it is how we learn.

The role that the knowledge and expertise students bring to the classroom should play in lessons has been a near-constant source of debate among stakeholders in education. There has been a recent surge of support, in some spheres, for the didactic, teacher-led approach, which adopts the view that time is “better spent” in lessons focusing on maximising the articulation of teachers’ schematic knowledge about the text and their “expert” interpretation of it - with a de facto framing of students’ knowledge as less useful or valuable.

Students’ interest in hip-hop was a powerful resource

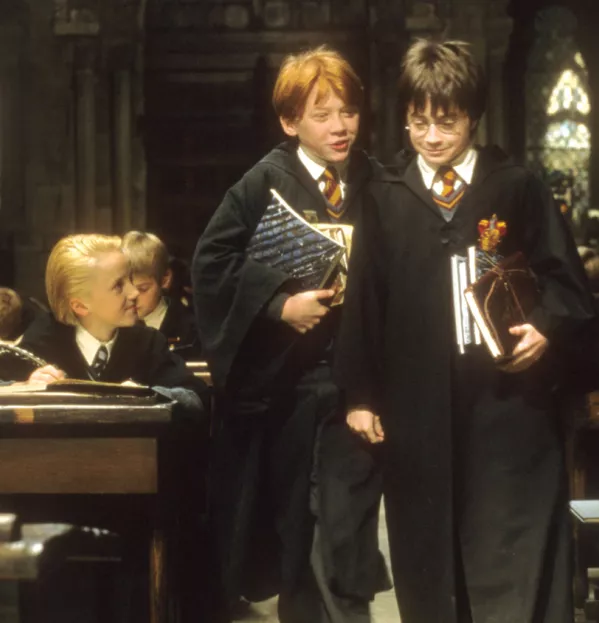

An unfortunate consequence of this view is that students’ schematic knowledge is often downplayed, and their reading of non-canonical texts, in particular, maligned. For example, young adult fiction regularly receives heavy criticism from some quarters. Teachers who do choose to engage this knowledge can be variously accused of dumbing-down, lowering expectations or pandering to students’ interests when they should (inferentially and sometimes explicitly) be teaching them about Shakespeare, Donne or Chaucer.

This fundamentally misrepresents the position adopted by most advocates for acknowledging student expertise who, by and large, suggest an integrated approach that involves the accrual of knowledge and “cultural capital”, and attending to the wealth of knowledge that students bring to the classroom with them: the two are by no means mutually exclusive. As we have discussed, this either/or view is also utterly contrary to what we know about reading and cognition.

Tapping into students’ schematic knowledge is also important since it means that students are likely to see the materials studied as relevant to them. Research in social psychology has demonstrated that personal relevance plays a key role in enabling students to become critical readers, and other studies have shown that making text and task choices personally relevant to students is important.

Personal relevance

For example, Richard Gerrig and David Rapp demonstrated that people were more likely to think and use previous learning in a critical way when they studied a text that had a clear personal relevance to them. In their must-read account of working in urban classrooms, Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade and Ernest Morrell show how teachers can draw on the wide range of literacies and cultural activities that form part of students’ lives outside of the classroom. They explain how their students’ interest in hip-hop music became a resource that they were able to use in a powerful way to encourage students to see learning as meaningful to them and to make connections between so-called canonical and non-canonical texts.

This discussion inevitably brings us back to the concept of a “challenging text”, since relevance is often unfairly equated with lacking challenge. The inaccurate conflation of these ideas can, we think, lead to approaches to English pedagogy that claim that units based around non-canonical texts are not academically rigorous and that units on “the classics” are valuable regardless of their actual content.

In other words, it results in a false logic that suggests that the most valuable use of English lessons is to load students up with this “better”, “more valuable”, “core” knowledge, at the expense of engaging and developing the schematic knowledge the students bring to the classroom. At best, this risks divorcing the study of fiction from students’ other narrative interests and expertise. At worst, it presents students with a sense that their own knowledge is useless or deficient; that to be educationally successful requires an abandonment of their home identity in favour of the better one offered at school.

Dr Marcello Giovanelli is assistant professor of English education in the Learning Sciences Research Institute at the University of Nottingham and Dr Jessica Mason works in the School of English at the University of Sheffield. They tweet @studyingfiction and blog at www.studyingfiction.com

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters