I’ve yet to meet a young person who thinks that Brexit is a good idea. Now I’m aware I might not be typical; I have a degree and live in a middle-class area. My father was a Jamaican immigrant; my mother the daughter of an Irish immigrant. I’m principal of an FE college serving a part of London that recorded one of the highest Remain votes of the EU referendum.

But surely the support for Remain shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone who works with young people. My students, like most young people I know, are instinctively international in outlook, used to the idea of being able to go anywhere in Europe to work, study or play. They use the internet to chat, game and gossip happily with people worldwide. “Taking back control of our borders” makes about as much sense to them as introducing a 9pm bedtime or making shops shut on Sundays.

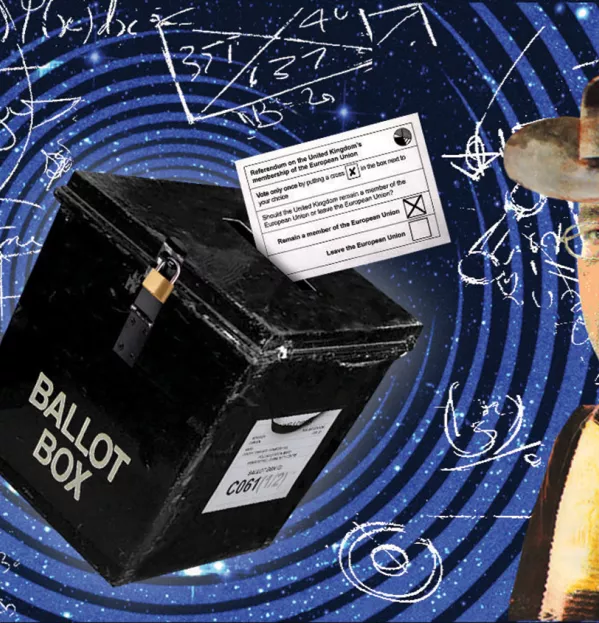

All the electoral statisticians indicate that around 70-75 per cent of 18- to 35-year-olds voted against Brexit. Many commentators have asked whether the result would have been different if more young voters had turned out. Writing in the Financial Times last year, data journalist John Burn-Murdoch said: “It’s technically possible that higher turnout among young voters could have yielded a Remain victory, but the levels of turnout required would have been so unprecedented that they would essentially only occur in a parallel universe.” Cue the Doctor Who music.

The general election shows that parallel universe is not too far away. Estimates of the turnout show an unprecedentedly high turnout of 18-35s, getting close to the level required to overturn Brexit.

Again, those working with young people won’t be too surprised. Like many FE colleges, we saw first-hand the dismay and anger of our students following the Leave vote. We put a lot of effort into encouraging them to register and vote this year, but we found that they were already determined their voice would be heard.

It is, after all, their future chances that are at stake. Since the referendum, they have examined the implications of tearing up the social, economic and educational networks across the EU that have helped this country achieve unprecedented prosperity. They don’t like what they see. Contemplating a future Brexit Britain, they reject the idea that leaving the EU will somehow make us a more open and fair society.

All around me in London, the economic and social benefits of an outward-looking, multicultural society shine. The serious problems are broadly about how wealth and opportunity is distributed, not where wealth comes from. How, my students ask, can the EU be blamed for that?

For young people, Brexit is a bad idea. They shouted that loud and clear in the election. As more become committed voters, politicians - still mostly acting as if somehow Brexit was inevitable - will ignore them at their peril.

Andy Forbes is principal of the College of Haringey, Enfield and North East London