YouTube: you scared?

Limmy was topless, his headphones were on, and a realistic-looking dildo was between his legs. He tugged on it, then bent over to lick it, before pretending, faux horror on his face, that he’d just realised his webcam was live-streaming.

Limmy is a very successful and very funny internet celebrity (1, see box below) - he started with a website, then moved on to podcasts. He’s had his own television show, written two books, and toured with his live shows.

But live-streams of him playing computer games, broadcast on YouTube, are his bread and butter (alongside online comedy videos like the above). I first watched a video of his several years ago, in which he demonstrated how to set fire to a character in the video game Grand Theft Auto IV. I’ve watched him many times since, mainly as he played Counter-Strike, a first-person shooter in which he led one team against another and then organised hilarious mass executions of the losers.

I realise that, out of context, it doesn’t sound very hilarious.

These days Limmy usually live-streams himself playing Overwatch, an online first-person shooter with over 30 million registered players. I’m not really into it. But I know a lot of people are, including a lot of teenagers. He talks throughout the game, and you can hear other players talk, and some of the comments are … unrestrained.

I ask him if he thinks that teachers should be concerned if teenagers are watching his Overwatch live-streams.

“They should definitely be concerned. Strangers in the voice chat can say anything, and there doesn’t seem to be a simple way to report people,” he responds.

For teachers to be concerned, though, they would have to know about Limmy. Most don’t.

Indeed, teachers don’t - can’t, rather - know a lot about what teens consume on YouTube. There are billions of hours of video (2) . It’s impossible for schools to police it - and neither is it their job to do so. But it would perhaps be useful for teachers to know a little more, particularly about what happens beyond the cat videos, movie trailers and music promos.

Which is why I was watching Limmy’s videos again, after all these years. Tes set me a challenge: teachers are overworked, underpaid, time-poor; they know their students are consuming YouTube daily but most don’t have the time or resource to see what their pupils might be being exposed to, what they are into and which channels are most popular. So offer teachers a glimpse, Tes said, journey into the YouTube world and report your findings.

What I found was that YouTube wasn’t quite what I thought it was - a hotchpotch of cat videos and amazing goals and old television theme tunes. There are also charismatic haters, hawkers and content some would find extremely disturbing.

So, teachers, let me be your guide: welcome to the world of YouTubers (3).

Way back in the olden days of 2015 (I’m channeling youth), US magazine Variety ran a survey to measure the rising popularity of YouTubers. Variety asked 1,500 13- to 17-year-olds to rank the personalities of 10 traditional stars and 10 online stars, using criteria such as approachability and authenticity, which are the standard ways of measuring influence in the advertising industry. Six of the top 10 slots on the resulting list were filled by YouTubers (4). People were shocked.

Well, older people were shocked. Younger people, who have grown up with online stars as part of the celebrity landscape, did what they always do: they shrugged then walked out of the door, wondering why the old people were so lame.

The fact is that older people, me included, have very little idea of the sort of thing that young people are watching online, which, according to a teacher I know (but who didn’t want to be named), is owing to the very nature of YouTube. “Kids’ relationships with YouTube are quite hermetic,” the teacher says. “They consume videos individually and share them, but assume, probably rightly, that adults are unaware of them.”

I respond that it sounds like a secret world that the children have to themselves. I ask if the videos come up in classroom chatter much.

“Sometimes, I talk to them in media studies about YouTube and I’m surprised by how much they like the most banal things, like haul videos and unbagging,” he says.

I was really clueless. I Google haul videos. What comes up is Zoella (pictured above), who broadcasts beauty and fashion videos to her 11.8 million subscribers (5). You’ve probably heard of her - she’s one of the YouTubers who has managed to cross over into the mainstream media. But there are thousands doing exactly as she does online. I watch one of her haul videos from 2015.

“Hello everyone, and welcome to Zoe’s haul video,” she says.

Then she addresses her little black pug: “Do you know what a haul video is Nala? It’s where I show everyone what clothes I’ve bought. Is that interesting to you?”

The dog provides no answer. Zoella cracks on regardless.

I ask my teacher friend if kids really like this stuff. He replies that he’d expected them not to, but some female pupils were “really keen” on haul videos. His female colleagues had also spotted the impact of make-up tutorial videos (6) - “elaborate and often quite inept contouring techniques,” he says.

Then he adds, “Thinking about it, it’s striking how gendered the whole thing is - the boys look at PewDiePie and so on.”

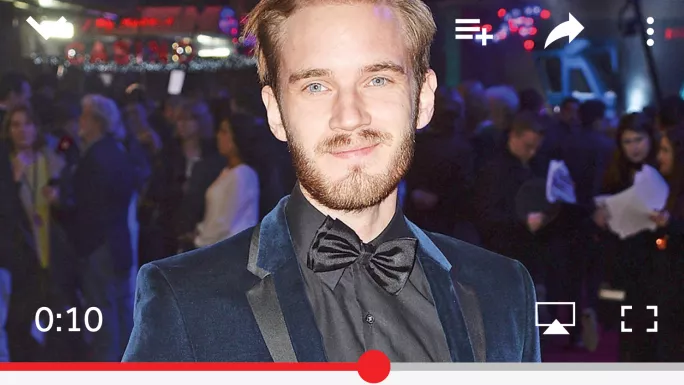

Ah, PewDiePie, real name Felix Kjellberg, the most successful YouTuber in the world. He live-streams videogaming to 56 million subscribers, including many British teenagers. Live-streaming gaming is massive. Like the beauty vloggers idolised by teenage girls, the gaming vloggers are followed relentlessly by millions of teenage boys (7).

PewDiePie is the biggest star in this arena. Several teachers I spoke to told me that his name comes up a lot in the classroom. All of them only had a very vague idea of who he was, though.

When I ask my teenage nephew, a keen online gamer, whether he is into PewDiePie, he pulls a face and says he isn’t keen, but as my teacher friend says, “It’s not unlike more conventional stardom - it’s cooler to like less popular stuff. Plenty of kids mock it, in the way they mock One Direction, but that doesn’t mean lots don’t have Harry Styles underwear.”

Now that I’ve discovered PewDiePie, I see him everywhere. Like Zoella, he’s managed to cross over. But where Zoella did so with book deals and eye-watering reported earnings, PewDiePie crossed over via infamy.

I first watched a video of his in April. Paul Joseph Watson, a right-wing YouTuber with 900,000 subscribers (8) who is also an editor-at-large for Infowars (“the tip of the spear in alternative media” is what it says on its Twitter profile), retweeted one of PewDiePie’s videos and added a comment to his retweet: “PewDiePie is dropping red pills about the media and YouTube censorship again.”

I clicked on the link (bit.ly/PewWatch). In the video, PewDiePie was in his studio. He’s a good-looking Swedish man with an engaging but zany manner. He introduced another video, which he played and commented upon.

YouTube is a matryoshka doll of content like that, with YouTubers often commenting on other content, particularly “mainstream” media, usually mockingly and amusingly, as a lot of us do privately. The technique makes the commentator seem “more authentic” than the forced smiles and banter of “the mainstream”. It’s also an easy way to create hours of content. “Fake news” is old news among teens - it has been a meme on YouTube for some time.

The video played by PewDiePie was a news broadcast about preventing children from watching unsuitable videos on YouTube. It featured two news readers in a studio. He paused it immediately to say, from a little pop-up box at the top left of the screen, “It’s already making me laugh, because I can just tell by looking at these two that they have no idea what the fuck YouTube is.”

He carried on commentating on the rest of the video. It wasn’t about PewDiePie, but he used it as an opportunity to remind people that there is a YouTube app for kids, as well as restrictions on the main app, and to tell his viewers that more 18- to 34-year-olds watch him than 13- to 17-year-olds (9).

The reason he did that is because he is on the defensive after years of being the top-earning YouTuber in the world (10). In a video PewDiePie (pictured above) published in January, two men held up a sign saying “DEATH TO ALL JEWS” while laughing and dancing. It turned out that PewDiePie had paid the men, who were in India, using the online freelance marketplace Fiverr, “to show how crazy the modern world is, specifically some of the services available online”.

Journalists were suddenly very interested in the content of all his videos and reported that there was other concerning material.

He replied with a statement on his Tumblr page (11) in February : “It came to my attention yesterday that some have been pointing to my videos and saying that I am giving credibility to the anti-Semitic movement … I want to make one thing clear: I am in no way supporting any kind of hateful attitudes … I think of the content that I create as entertainment, and not a place for any serious political commentary. I know my audience understand that … Though this was not my intention, I understand that these jokes were ultimately offensive … to anyone unsure on my standpoint regarding hate-based groups: No, I don’t support these people in any way.”

The statement didn’t work. Disney quickly cancelled a joint venture it had with PewDiePie and YouTube dropped him from the premium advertising program.

In the video I was watching, he was defending himself. With the news report over, PewDiePie adopted the concerned tone of a parent and said: “Have you heard about PewDiePie? I heard that he’s a Nazi. I don’t want my kids watching no Nazi.”

Then in his real voice, he continued: “I don’t even want kids to watch me, all right. Like, I’m not, clearly not … I’m not… I think I used to, but I don’t cater to kids, like, it’s not what I do.”

But on YouTube, you don’t get to choose who watches you.

Let’s be clear, PewDiePie and Zoella are just the two most popular people who do what they do at the moment, in two of the most popular vlogging areas. YouTube is a very fickle world, and those who stay at the top for long periods are rare - many rise to millions of views and fall to nothing with brutal haste. Many never get many views at all.

Influencing young minds

What is the impact of this troop of vloggers? I talk to 22-year-old Zayne Kadry, a psychology undergraduate at the University of Portsmouth, about the influence that PewDiePie and Zoella have on their viewers. I went to Zayne because there is very little research out there on YouTubers at the moment, but Zayne had done a thesis about the level of influence of Zoella and PewDiePie specifically - Zoella when talking about a particular make-up product, and PewDiePie when playing a particular game.

“I did a before and after of the products,” explains Kadry. Participants in the research were asked to agree to a greater or lesser extent with statements about the product, such as whether they liked it, and whether it was easy to use. Then they watched the YouTubers’ videos or a traditional advert and responded to the statements again. The YouTubers had a greater impact than the adverts (12).

Kadry is an undergraduate, and her research was within that context, but her study made her realise something that she noted for future research: the influence of YouTubers goes beyond mere products.

Which is the worrying part. Yes, children might want to buy a new jacket or play a new game, but also, they may absorb their politics from YouTubers, who don’t abide by the same standards as television and radio, and who may need to shock to gain followers. How is that influence going to grow in the future?

According to the BBC, most teenagers have been active on social media starting from the age of 10, so parents like me, with three young children, can no longer put our heads in the sand about who our children are watching.

For instance, have your children watched Tampon Girl? “The most hated YouTuber, who no one who’s over 18 has heard of, is Tampon Girl,” says Heather Mendick, a freelance academic researcher.

Mendick and three colleagues have spent two years looking at the relationships between young people, celebrities and aspirations, including a substantial amount of time looking at YouTubers. Their findings will be published in a book by Bloomsbury next year (13).

“Tampon Girl is absolutely fascinating,” she continues. “It’s one of the few videos that’s been taken down from YouTube repeatedly for taste and decency. It keeps getting reposted. She’s a teenager from the States and she posted a video of herself. Offscreen she allegedly takes a tampon out, then onscreen she sucks the tampon until it’s not red anymore. Then offscreen you hear her throwing up. So I don’t know whether she does throw up or not.”

What? What? What?

It takes a while before the word actually comes out of my mouth: “What?” I ask.

“I know,” says Heather. “It’s a phenomenal video. You should watch it.”

I’m not even sure if it would be legal for me to watch it.

“Why did she do that?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” says Mendick. “Why not? I mean, Germaine Greer back in the 70s said in The Female Eunuch, if you haven’t tasted your own menstrual blood you have to wonder how liberated you are. I don’t think it was a feminist statement, but there are reasons you might do it. The thing was, there was a lot of disgust at the idea - women’s bodies always provoke disgust in that sense - but also she was seen as an overnight sensation, someone who didn’t deserve to be famous. She was seen as fake.”

I look up Tampon Girl on the internet. I watch a bit of her video, but it ends before she sucks the tampon. I don’t try to find the full version. Instead, I watch another video she put up, in which she said she regretted the original video and then apologised to celebrities caught in the social media aftershock. (We have not linked to these videos, or used her real name, owing to the sensitive nature of the case.)

Mendick says a lot of people doubted whether it really was a used tampon, which damaged Tampon Girl’s influence.

“Some people talked about there being some red dye in the corner of the screen, and so they think again: not being authentic,” she says. “When people break those kind of virtuous codes of hard work and authenticity and entrepreneurship, they’re derided. She got a lot of hate, Tampon Girl. There were stories that she killed herself.”

Those stories are, apparently, a hoax. But her example shows what some young people will do to emulate their YouTube heroes and try to create influence for themselves. I can imagine a young Limmy fan watching him fellate a pretend penis, then doing something shocking in an effort to establish their own brand, which is how kids apparently foresee themselves online (14).

“There’s a whole sort of self-branding thing that goes with YouTube,” says Mendick. “You’ve got to kind of take yourself and commodify yourself in a sense - to turn yourself into a product. That’s what the ideal YouTuber does.”

And a lot of young people understand that very well, she adds, and know about gaining followers, getting “partnered”, then making money. But what some may not understand is that YouTube success depends on fame, which by its nature is rare.

“The number of people who actually make a viable career out of YouTube compared to the number of people who post on it is tiny,” says Mendick. She argues that it’s part of the myth of meritocracy.

“So that idea is misleading young people?” I ask her.

“Yeah,” says Mendick, “in the sense that it’s misleading all of us.”

I can’t tell you everything about YouTube, because no one can. Physically, it is too big. I spent hours trawling the videos: they are extremely varied.

Some are very, very entertaining, and funny, and refreshing. Some are incredibly informative and give students access to a wealth of information, opportunity and expertise (15). But some would be deemed unsuitable for under 18s and some of the seemingly innocent vloggers have the power of influence that merits adult scrutiny.

Given more time and more words, I could tell you how gangs use YouTube for gloating, recruitment and increasing their status; or how hordes of young people try and do a Justin Bieber, hoping to be “discovered” as a musical phenomenon on the platform.

We can’t police it, but we need to acknowledge that it’s an addictive relationship; it would be foolish to ignore the influence of YouTube on teenagers.

I ask Mendick if teachers should worry about pupils watching YouTubers.

“I suppose if you worry about what TV people watch, in that sense it’s really no different,” she replies.

But to worry about vloggers en masse, says Mendick, would flame the “moral panic” about the internet.

Ultimately, it is for parents to try and restrict their children’s use of the internet, if they wish to. YouTube has plenty of tools to allow them to do that (16).

For teachers, it is more about watching YouTubers to get an idea of what teenagers and younger children are watching, then keeping an eye on certain YouTubers rather than YouTube in general. It may seem a chore, but it goes towards a greater understanding of the young people being taught, and that understanding is crucial not just for learning but for safeguarding and so much more.

As Mendick tells me: “If adults are going to make decisions about young people, then we should learn about young people.”

Andrew Hankinson is a freelance journalist

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters