Anti-vaccination propaganda puts pupils and teachers at risk

There are many ways to celebrate your coming of age; getting yourself vaccinated isn’t generally one of them. But for Ethan Lindenberger, who had grown up with anti-vaxxer parents, being confronted with the overwhelming scientific evidence that vaccination works led to a decision to get immunised against six diseases, including measles, mumps, rubella and polio.

The Ohio teenager achieved notoriety through a post on social media site Reddit that went viral: “My parents are kind of stupid and don’t believe in vaccines. Now that I’m 18, where do I go to get vaccinated? Can I get vaccinated at my age?”

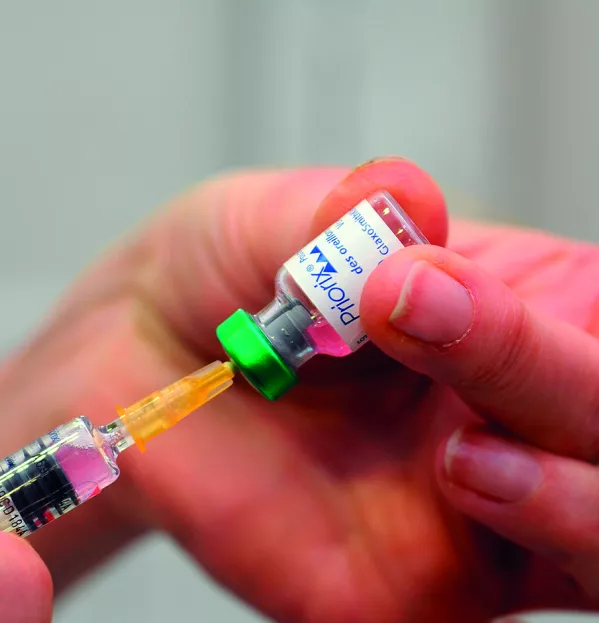

Vaccination is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions developed in the 20th century. It has dramatically reduced the number of deaths from measles and other diseases.

According to the University of Oxford’s Vaccine Knowledge Project, it is estimated that, since 1990, more than one in five of all child deaths averted have been due to measles vaccination. Since a vaccine was introduced in the UK in 1968, Public Health England estimates that 20 million measles cases and 4,500 deaths have been averted in the UK.

But, sadly, measles - one of the most infectious diseases - is making a comeback. Much of this is driven by parents refusing to vaccinate their children for various reasons, including the now totally discredited link with autism, the belief that vaccines are “unnatural”, conspiracy theories and, of course, fake news.

Measles prevention is in some ways a victim of its own success. These days, people often dismiss it as an innocuous childhood illness. They have not seen children die from it or witnessed the awful complications it can cause, such as pneumonia and encephalitis (swelling of the brain) that can lead to convulsions and leave a child deaf or with an intellectual disability.

It’s not only measles we need to worry about, however. It may be the “canary in the mine” for other preventable illnesses, says Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “What we will see is the return of some of the oldest diseases that we had under control.”

Coverage for the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is now at its lowest point for six years. To achieve “herd immunity”, we need 90-95 per cent of the population to be inoculated. Although sufficient numbers of children receive their first dose, only 88 per cent are getting the second.

Schools are inevitably on the front line and, not unreasonably, some European countries will not allow children to attend without proof of vaccination. A resurgence of measles poses a threat not only to pupils who may be immunocompromised but also to babies on the premises who are too young to be vaccinated.

It is also a threat to unimmunised staff (not everyone knows their full vaccination history), especially those who are pregnant and may be vulnerable to complications such as miscarriage, preterm birth, neonatal low birth weight and even maternal death. Teachers who haven’t had two MMR doses are similarly “at risk” of contracting mumps and rubella, which is also dangerous for women in early pregnancy (see tes.com/news).

Immunisations work because societies unite to protect each other by preventing the spread of disease, which is why herd immunity is also known as “community immunity”. Our most important communities are our schools. If we can’t persuade parents to protect not only their own child but everyone else’s, too, we can at least give children the facts from an early age, so that, like Ethan Lindenberger, they can eventually protect themselves.

@AnnMroz

This article originally appeared in the 22 March 2019 issue under the headline “This epidemic of anti-vaxxers puts pupils and teachers at risk”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles