Calm, not chaos, rules at school where play is king

The P1 area at Canal View Primary School is like one of those old optical-illusion posters that university students used to love putting on their bedroom wall: it’s hard to see what’s going on at first - and it’s a little disorientating - but soon a clear picture starts to form.

The school in Wester Hailes, one of the most deprived parts of Edinburgh, is trying something bold with its 54 P1s. Rather than being split up into larger classes, they are mostly free to wander between three classrooms and an outdoor area, deciding for themselves if they want to mess around with water, create some Plasticine jewellery or build a giant car with wooden blocks. Many have talked up play-based learning over the years, but this school really means it.

The scene might at times seem chaotic to a visitor, but there is an overriding sense of calm. The occasional hubbub, when a child becomes upset or their frustration bubbles over, tends to subside quickly. Like a tightrope walker swaying in the breeze, those children manage to right themselves; some have made remarkable progress in gaining control over their emotions and staying on track with their learning.

Three P1 teachers oversee proceedings alongside an early years practitioner, a pupil-support assistant and, two days a week, a speech and language therapist. Each teacher ostensibly takes about a third of pupils, but children mix at will in carefully designed and continually refined learning areas dotted around each room, from a water table to a set of huge Lego-style wooden blocks, to a box of modelling clay, cookie cutters and rolling pins.

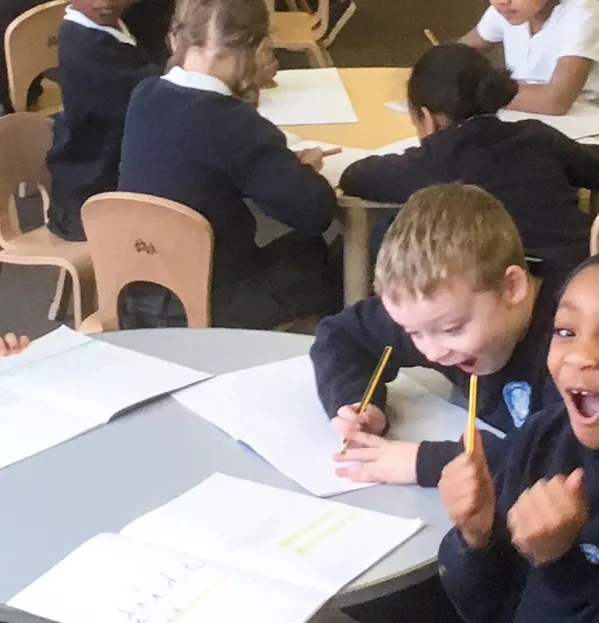

While the scene resembles a nursery, the day is punctuated by more structured class sessions; during our visit, for example, one group is trying to master writing the letter G. However, staff are always keeping a careful eye on pupils’ progress; they will subtly move children around and provide individual help, depending on their needs.

“We have completely changed the way that we approach P1 at Canal View,” says teacher Susannah Jeffries, who adds that staff felt nervous when this all started in August, as if walking a “tightrope” of their own. They were reassured, however, that research showed a more rigid classroom was not developmentally appropriate at P1, especially for those with challenging social and emotional needs.

Focused and personal

Canal View pupils arrive in P1 at “wildly different stages”, say staff. Never mind writing their name, some children toil with the very concept of expressing themselves through squiggles on a page. But you would struggle now to pick out pupils who at the start of the year developmentally resembled children half their own age - throwing themselves to the floor in frustration, acting aggressively around peers and struggling to express themselves with a limited vocabulary. Such children can now be seen embroiled in delicate discussion over how to share out Plasticine quotas, or planning intricate schedules for baby dolls.

While children play and develop a range of social and academic skills, staff work with them in small groups, sometimes one to one, with short spells of direct instruction appropriate to their level, in a way, says Jeffries, that is “focused, measurable and personalised”.

Early in the day, one boy becomes upset and teacher Aine O’Shea is able to take the several minutes he needs to sit on the floor with him, give him a cuddle and cajole him back on track; other pupils pay no heed and carry on with what they are doing. O’Shea says the Canal View approach to P1 is “a world apart” from what she has seen elsewhere: children do things when they are ready, rather than teachers “ploughing on and hoping that everyone will magically catch up”.

Similarly, explains depute head Bex Carter, if a child has an aptitude for, say, art, they can keep going until their masterwork is finished, rather than rushing to get it done. A guiding principle at Canal View is that every child should go home each day glowing with the satisfaction of something about their learning that made them happy.

The role of early years practitioner Kirsty Dobson has been crucial, the teachers say, in encouraging play that will challenge children and help them progress without compromising the freedom that has helped them settle in school. Jeffries says: “I was really aware that when you are doing something new, it is so easy to gravitate back into patterns that are familiar and comfortable, and to apply too much structure to the setting, which would dent the original intentions.”

Calming influence

The teachers smile at memories of typical P1 cohorts arriving in echoing gym halls, their first urge being to run around in circles, yelling with abandon as they burned off pent-up energy. This group, however, is markedly different, and will file in calmly and settle quickly - a reflection, staff believe, of how at ease they are with their school.

This is not a given: many pupils arrive with complex needs - more than 80 per cent of those at Canal View are in the top two deciles in the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation - and could quite easily find school a depressing place where they repeatedly fail and get told off.

“We are working hard to ensure that they do not fail, from their very first experience in school,” says Jeffries. So, for example, when teaching phonics to a whole class in a typical school, children are often expected to learn specific sounds at around the same time; in Canal View, pupils go at a pace less likely to alienate them from learning.

The Scottish government published a national play strategy in 2013, stating that play must be embraced “if we want Scotland to be the best place in the world to grow up”. A recent government-commissioned survey on pupil behaviour, however, found concerns among teachers that early, play-based learning had a negative effect as children grew older (see bit.ly/PrimaryPlay).

But Jeffries says: “Oddly, by removing the traditional structure from the day, we have opened up the time and the space to teach the children the skills they will need to cope with the structure that is to come.”

It remains early days and Carter says the full impact will likely not be known until this cohort reaches upper primary. But the school has children, who would otherwise have found P1 to be incredibly difficult, making “giant leaps” in social and developmental progress - and taking big strides academically.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters