Can ‘holiday hunger’ schemes curb summer learning lag?

Many Scottish pupils start the autumn term nearly five weeks behind where they were before the summer holidays, new research has found.

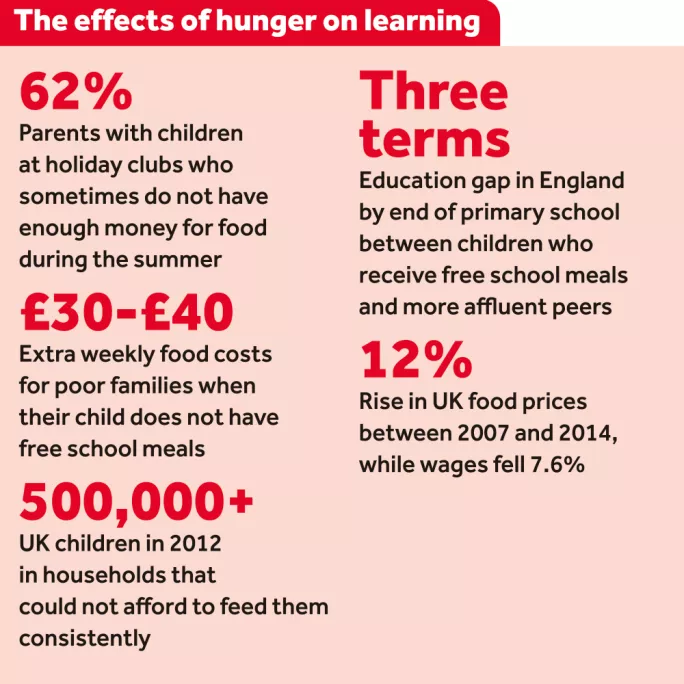

The figures demonstrate the huge impact of unhealthy eating habits and hunger during the summer holidays, particularly among the country’s poorest children.

Previous research has demonstrated a “summer learning lag” among pupils in the US, but until now the effects were not believed to be as strong in Scotland, where the summer break is far shorter.

However, the new findings by Northumbria University researchers show that attainment among poor six- to eight-year-olds in three areas of Scotland and England dropped to about four-and-a-half weeks behind where it was before the summer break - similar to the reversal identified in US studies.

The research also shows that opening school doors to families out of term time can boost children’s educational prospects - but this is being hampered by the “piecemeal” availability of summer schemes.

The researchers surveyed 428 different organisations that provide food to children who might otherwise be hungry during school holidays - the first time such an exercise had been carried out in the UK.

A separate pilot study analysed the educational impact of three such programmes - two in Scotland and one in north-east England. A third piece of work explored 256 parents’ views.

Lead researcher Professor Greta Defeyter, an expert on school breakfast clubs and holiday hunger, said the findings were significant as the attainment gap between rich and poor - which first minister Nicola Sturgeon has said is her top priority - “could actually be driven by the summer period”.

The research found that the summer schemes - which often give children access to books and healthy food - helped to boost reading scores and stop body-mass index levels increasing, although spelling did not see the same uplift.

But Professor Defeyter said summer schemes were “piecemeal” and unregulated, which minimised the benefits. The survey suggested that they often focused too heavily on educational activities, when simply getting children to eat might be more important.

Some of Professor Defeyter’s research was incorporated into Labour MP Frank Field’s All-Parliamentary Party Group on Hunger, which reported in April.

But she revealed her detailed findings at a Children in Scotland conference on food and attainment in Glasgow last week.

Holidays could be “a time of huge pressure and stress” for families, said Professor Defeyter after her presentation.

Hungry or malnourished children could suffer from dental problems, frequent stomach aches or headaches, aggressive behaviour and psychiatric distress; they also fall behind academically, especially in maths and spelling.

“If you have poor teeth, if you have a pain in your mouth, trust me, it will affect your learning. If you’re hungry, you won’t learn very well,” said Professor Defeyter.

Professor Defeyter’s team explored the impact of the three summer schemes on 121 children aged 6-8, which she said was the first research of its kind in the UK.

Andrea Bradley, assistant secretary of the EIS teaching union, said she welcomed “properly funded summer holiday schemes” that provided children with food, but cautioned that these “should not depend heavily on individual teachers’ goodwill or short-term funding pots, as has sometimes been the case”.

A recent EIS survey of teachers showed more than half of respondents had seen an increase in children coming to school without play-pieces, snacks or tuck-shop money.

Ms Bradley said it was “highly likely” that a growing number of children were going hungry in the summer holidays.

Children in Scotland chief executive Jackie Brock said: “Though this research is in its early stages, the findings are potentially very significant for the way we develop policy to support improvements to children’s learning and wellbeing in our poorest communities.”

There were “big implications” for attempts at raising attainment, and it also showed how community leaders and businesses could support schools in the summer.

However, a Scottish government spokesman suggested the evidence linking holiday programmes to attainment was “anecdotal”. He said: “We are aware of studies suggesting that breakfast clubs and holiday activity programmes can contribute to children attaining better, and there is much anecdotal evidence that attendance contributes to children’s ability to make best use of the education offered to them.”

He added that it was up to local authorities to decide whether spending their funding on summer schemes was a priority.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters