Character education: what role should schools play?

I wonder if you would agree with me that bringing up children is not easy? I suspect there will be many of you concluding that this is a tautology, that somehow difficulty is inherent in the nature of the task of bringing up children. This does not, of course, mean it isn’t a labour of love, but getting it right is tricky and fraught with complex decisions about what the right thing is to do. It is made all the more difficult because none of us has yet found the instruction manual.

A colleague recently touched upon this in an assembly. He set out a range of scenarios and encouraged students to consider how they would act. Similarly, at a recent parents’ evening conversation turned to how we support children to make the right choices, what we do to provide a context or shape a paradigm that allows them to navigate life.

Such concerns are central to how we think of education in 2019. The children we raise today are faced with a world that challenges them and tempts them - largely due to, but not exclusively because of, the rise of digital and social media, and the decline of many of society’s traditional pillars. In this context, we are now on our third successive education secretary who has made developing character education a central policy.

So where do schools fit into this? What is their role? Or are they simply machines for generating exam results that should not attempt to teach beyond the curriculum?

Roaming charges

I am sufficiently old enough to support the view that some things are inherently or intrinsically wrong. Hurting others, being untruthful, acting without regard for the person at the end of your actions are wrong.

There is and has always been, however, a school of thought that supports a view that all moral claims are subjective and that there are no moral absolutes.

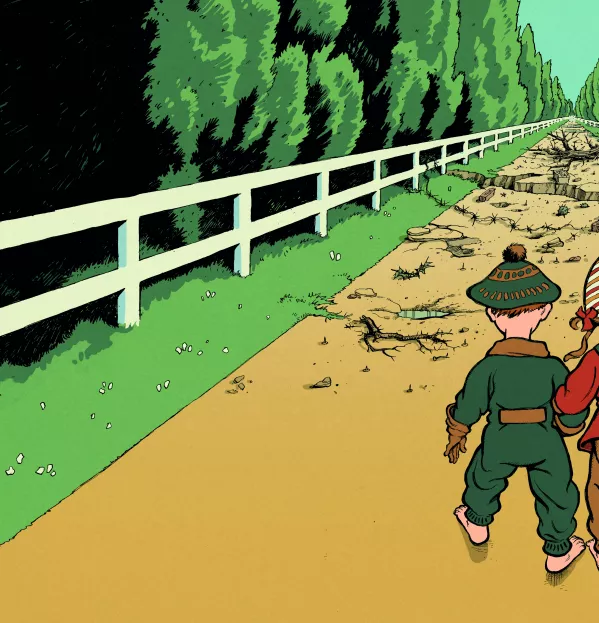

I don’t agree. I believe that this view removes the necessary support railings that allow us to be fully human, by suggesting that the absence of any barrier allows you to realise yourself. It is akin to thinking that going barefoot allows you the opportunity to roam where you please. This is hardly the case, as the unshod soon discover on rougher ground. You might well argue that having a set of principles is not important, that when the choices come, you can decide as you go, weighing each decision in the context in which you find it.

But my concern with this is: how is the decision being made? Without a set of guiding principles, you are inventing a moral system of choice for every context.

There are elements of my thinking that betray the rule deontologist in me. As I said earlier, certain contexts require a particular response: we have a duty or a moral imperative to act, and failure to do so is unacceptable. It is also the case that we are all too human and missing the moral mark is unavoidable. Aristotle had a word for this, albeit applied to his understanding of the hero’s fall from grace in Greek tragedy: hamartia. We fall short or, as hamartia means literally, we miss the mark.

Roughing it out

I would argue that on the rough ground of adolescence, children need the security of being supported, they need to be shod. Roaming discalced may afford the freedom to feel the grass under your feet, but what happens when the going gets rough? Adolescents need the consistency of that framework of decision-making that they acquire through a catalogue of interactions with what you do and do not find acceptable.

While they may rail against the parameters you set, they need them. But the character-defining examples do not come from single acts of spectacular heroism in moments of enlightened moral acuity where the right thing is done in sepia and recorded as a Hallmark greeting card. The saccharine depiction of the ease of this superficiality betrays the many pulls on the deontologist in our children.

In a time of moral choice, they feel a duty to friends, to principle and to being the “self” they want to be. It is quite a different moral decision game when enacted in the incremental options played out in the playground. But be under no illusion: the formation of character in our children is a long process of missing the mark, of trying, failing well and trying again.

It is easy or convenient to give in, and don’t we all? But it is in those moments where we quietly and grudgingly surrender a decision because of fatigue, the desire to feel loved or to avoid Armageddon that character is formed, and children learn the right thing to do, or not. It is beyond textbooks or the esoteric climate of cosseted cognition.

If they are to walk through life’s decisions, they need discernment. If they choose to be discalced and roam as they please, they do so because through our help they know how to put their shoes on when the time comes.

This is the role of parents, of course, but schools too. It is our duty as educators to help those in our charge build their own framework of beliefs, something that can help them navigate an increasingly morally ambiguous and challenging world.

Cliff Canning is head of Hampshire Collegiate School

This article originally appeared in the 28 June 2019 issue under the headline “The walk of life requires good soles”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles