This country owes a huge debt to Catholic schools

This year marks the centenary of the Education (Scotland) Act 1918, which is rightly perceived as a defining moment in Catholic schools becoming part of the state-funded school system.

Section 18 of the act addressed the transfer of voluntary or denominational schools. It did not specifically refer to Catholic schools but rather to a wider range of institutions, including Episcopalian schools and a small number of Church of Scotland and Free Church of Scotland schools that had not transferred following the Education (Scotland) Act 1872.

Nevertheless, section 18 offered conditions that were highly advantageous for Catholic schools, many of which were struggling with financial challenges and relying on fundraising endeavours. Catholic schools were often characterised by large class sizes, inadequate resources and unsatisfactory working conditions. There were also serious issues concerning fair remuneration for teaching staff.

The 1918 act made provision for: the sale or lease of the Catholic schools; the retention of denominational status; the continuation of the practice of religious instruction and observance; the right to approve the religious belief and character of the teachers; and a very welcome parity in the pay scales for teachers in Catholic schools. Perhaps surprisingly, the initial choice for many Catholic dioceses was to lease the schools rather than to sell, although by the late 1920s most Catholic schools had been sold to local authorities.

There are different ways of interpreting the introduction of the act. It can be perceived as altruistic, in aiming to include Catholic schools in the state-funded sector, to ensure equity of educational opportunity. The focus was on the inclusion of children from a largely impoverished community that constituted a sizeable minority, especially in the West of Scotland. But it can also be perceived as a government response to pressure from a vocal and persistent Christian minority to accede to specific demands for funding for their schools, helping them to retain their religious identity in a country that did not appear to be very tolerant of Christian diversity and, at times, could be openly hostile.

It can even be considered to have been driven by an agenda of increasing centralisation - the need to consolidate government interests and influence in all the major forms of school education to enable some form of social control. To these can be added a more contemporary interpretation of the justification for Catholic schools: that they represent an example of the neo-liberal principle of greater choice in state schooling.

Faith and doubt

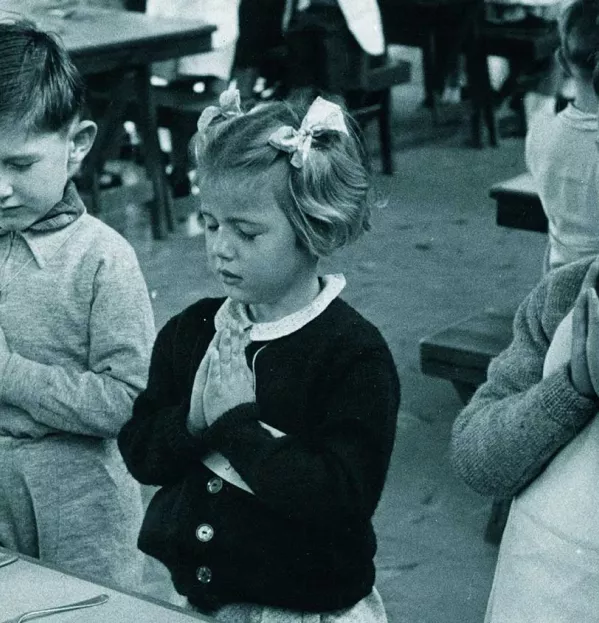

From the perspective of the Catholic Church, these schools offer education based on explicit Christian values and are part of the mission of the Church to engage in the work of education and faith education, to serve the children of the Catholic community and the wider Scottish community.

Despite the varied justifications, a number of serious issues remain around the continued existence of state-funded Catholic schools.

The challenges to Catholic schools include some classic arguments questioning the existence of any form of faith schooling in a state-funded system - the idea that it is not the state’s role to be involved in, or to contribute to, any form of faith formational or confessional schooling. There are also recurring accusations that Catholic schools create divisions and divisiveness; that they signify a form of government endorsement of “sectarian” schools, or schools that might maintain or foster sectarianism or sectarian attitudes.

These are seldom substantiated or supported by research evidence. Most recently, the Advisory Group on Tackling Sectarianism in Scotland, chaired by Dr Duncan Morrow, categorically rejected these claims, stating in a 2013 report (bit.ly/Morrow2013): “We do not believe that sectarianism stems from, or is the responsibility of, denominational schooling, or, specifically, Catholic schools, nor that sectarianism would be eradicated by closing such institutions.”

Catholic schools are sometimes considered to privilege the educational interests of a particular religious group, although this position arguably holds less currency in the current climate of a more diverse pupil population. Contemporary Catholic schools are more inclusive than their predecessors, and sensitive of the need to educate all children in their care while retaining a Catholic identity.

There are other challenges for Catholic schools, such as negotiating changing social mores and attitudes, including around the public and legal recognition of gender and in the understanding of religious identity. There are difficulties in recruiting a sufficient number of Catholic teachers (alongside serious challenges in the recruitment and retention of teachers more generally in Scotland). And there are recurring questions about the justice of the exclusive staffing of Catholic schools - teachers being approved in terms of their religious belief and character.

The debates around state-funded Catholic schools continue to be articulated periodically (and often misrepresented) in the media. It is perhaps helpful to explore one way in which they have contributed to children’s education in Scotland. In 1817, the Catholic Schools Society was set up in Glasgow to cater for the children of the growing Catholic workforce. A principal aim was to educate children from backgrounds of poverty and deprivation. This mission to educate the poor continued through the 19th century, intensified by the arrival of large numbers of Irish Catholics during the series of famines in the middle of the century. It persisted in the years of depression and continues into the present day: there remains a strong consciousness of a historical and contemporary dedication to the education of the poor that has a deep-rooted Christian motivation. This dedication is inclusive of all children in Catholic schools - irrespective of their faith or values background.

There is also ample evidence that the quality of the education provided in state-funded Catholic schools is equal to any comparable non-denominational school, in terms of attainment and achievement. Catholic schools, for example, have fully participated in initiatives to close the attainment gap.

State-funded Catholic schools in 2018 are both celebrated and contested, and there are ideological and philosophical objections to their continued existence. Perhaps these debates could include a greater awareness of the important contribution of Catholic schools to the education of the Catholic community - and to the wider Scottish population.

Professor Stephen J McKinney is leader of the research and teaching group Pedagogy, Praxis and Faith in the University of Glasgow’s School of Education. He is a past president of the Scottish Educational Research Association

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters