Do Scotland’s exclusion figures tell us the full story?

There is very powerful evidence that being excluded from school is extremely damaging for children and young people. Those who are most likely to be excluded are already amongst the most vulnerable in society - a recent Institute for Public Policy Research report points out that they are more than twice as likely to have been in local authority care, four times more likely to have grown up in poverty, seven times more likely to have a special educational need and 10 times more likely to have poor mental health. These disadvantages are compounded by being excluded from school, which can all too often lead to stigmatisation, prolonged periods out of employment, a criminal record and poor physical health.

It is not surprising, therefore, that policymakers and educationalists are striving to reduce the rate of exclusions - but they seem to be having more success in some countries than others. National figures released by England’s Department for Education show that nearly 7,000 pupils were permanently excluded there in 2015-16. Overall, the number of exclusions has increased in England by 40 per cent over the past three years to the extent that, on average, 35 children each day are being permanently excluded from school.

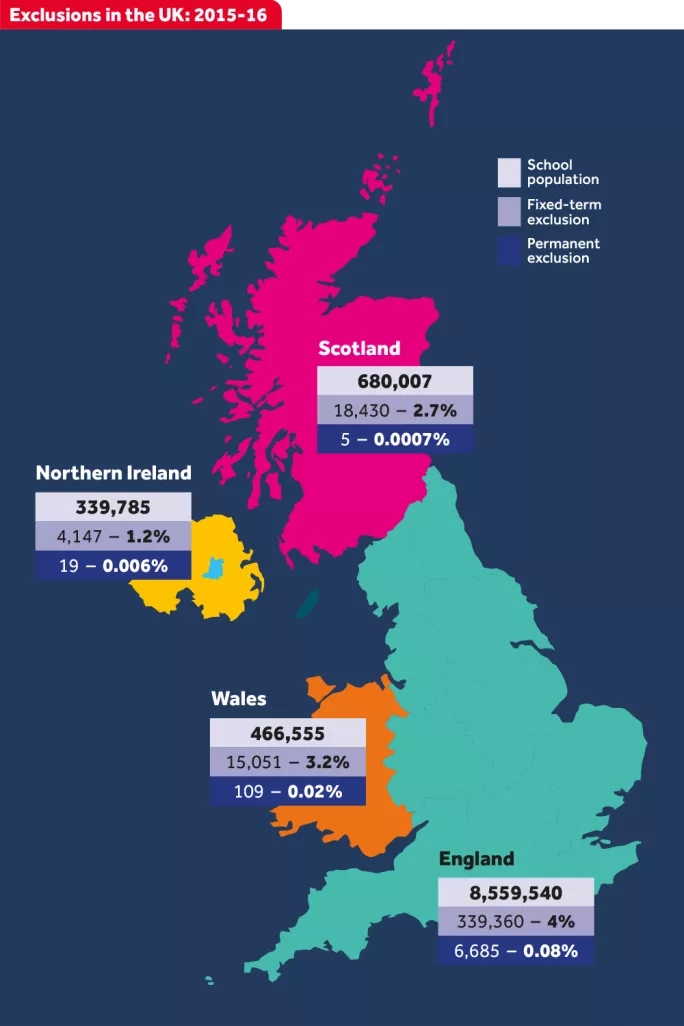

This pattern is not reflected elsewhere in the UK. England has the highest rates of both fixed-term and permanent exclusions. Of course, England has the largest school population, so it is not really useful to compare crude numbers.

Nevertheless, it is notable that in 2015-16, when many thousands of pupils were permanently excluded in England, this was the case for only five pupils in Scotland. Not only are the overall rates of fixed-term and permanent exclusions higher in England, but also while the rates have been increasing there, they have been falling elsewhere.

Explanations for these divergent patterns often focus on the different policy regimes across the UK, holding that Scotland and Wales, in particular, have more “inclusive” education systems. For example, people cite the “marketisation” of education, which is more pronounced in England than elsewhere in the UK and which, it is claimed, creates pressures for schools to exclude any students who will negatively affect their performance data and “league table” positions.

Also, the reinvigorated traditionalism that has been seen in England may well have increased the disengagement of students who struggle academically. It requires greater levels of conformity to school rules. There is, for instance, frequent press coverage of students who have been excluded from schools in England for misdemeanours such as not wearing the right uniform or wearing too much make-up. Plus, the huge expansion of academies and free schools in England has meant that there are very few centralised resources left to support students “at risk” of exclusion.

The other UK nations have chosen not to pursue these kinds of reforms. In Scotland and Wales, there is an ongoing commitment to the “comprehensive” ideal, a rejection of education “markets”, a continuing belief in the value of local authority services and the introduction of a progressive curriculum that is designed to engage all learners. In Scotland and Wales, there has also been a real drive to stop schools excluding students for anything other than the most extreme incidents.

However, while there is no doubt that Wales, and Scotland, in particular, are successively reducing official levels of school exclusion, it does not mean that schools there are not developing other strategies that effectively exclude students from the mainstream classroom - even though they are still on the school register. Certainly in Wales, and most likely in Scotland, there are a range of practices that can be considered “exclusionary”.

Internal problems

In addition to “managed moves”, whereby students at risk of exclusion are transferred to a new school, thus avoiding the stigma of exclusion, schools appear to be using a wide range of “internal exclusions”.

These can involve moving the student to what is effectively an internal pupil-referral unit (PRU), where they will almost certainly receive a diminished curriculum alongside a series of therapeutic interventions. Not only is there very little evidence that these kinds of interventions have successful outcomes (other than removing the student from the class), but they are also resource-intensive. And, as with so many other aspects of education, schools with the most disadvantaged students are having to invest most heavily in these arrangements.

So, while Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can be justifiably proud of their lower levels of official school exclusions, the problem of internal exclusions is likely to be pervasive.

Without wishing to deny the damaging consequences of official exclusions, it is almost certain that these other forms of exclusion will have negative consequences. Until the effects of these other forms of exclusion are known - at individual, institutional and system level - we should not assume that a school or system is necessarily any more or less “inclusive” on the basis of official data on school exclusions alone.

Professor Sally Power is co-director of the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (Wiserd) and recently spoke at the annual conference of the Scottish Educational Research Association (Sera)

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters