Education’s funding crisis: what happens when the money runs out?

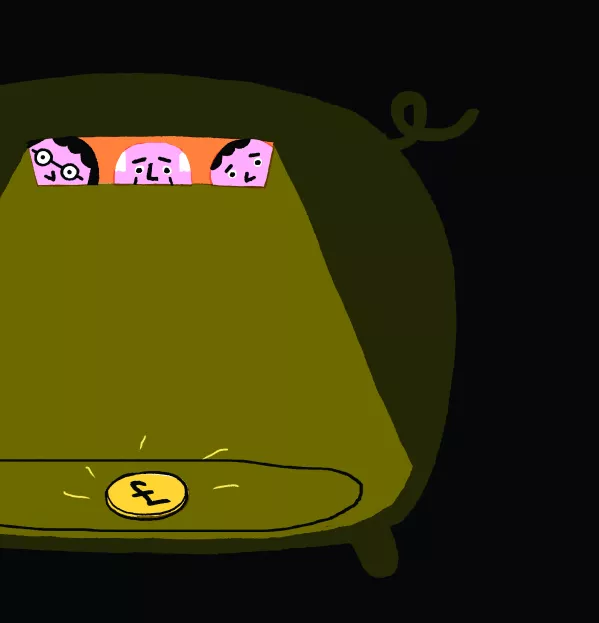

Michael Ferry has been struggling to sleep at night.

Two weeks ago, the secondary headteacher was preparing to announce that five members of staff - both teachers and support staff - would be at risk of redundancy. In the end, he managed to find cost savings from elsewhere. But Ferry knows that there are more hard decisions ahead. He is long past the point at which he could make cuts without seriously affecting his school’s provision.

“You wake up at two o’clock in the morning and can’t get back to sleep because you’re thinking, ‘So-and-so might be leaving, so how can I maintain the curriculum but still save the money?’ or ‘How am I going to tell so-and-so that their contract isn’t going to be renewed?’ ” he says. “It’s awful, every bit of it.”

The only way he has been able to balance the budget at his school, St Wilfrid’s Catholic School in Crawley, West Sussex, is by not replacing staff, not renewing contracts for some and reducing contract time for others. There will be no cover for two staff going on maternity leave this summer. Even then, the school, with a budget of £4,936,937, is only just on course to be in the black for the 2019-20 year - to the princely sum of £118.

It’s a familiar situation for school leaders up and down the country, facing seemingly unprecedented cuts that threaten the hard-won gains of recent years. And the question for many is: how long can this go on? At what point does the situation become unsustainable? What happens when a school finally runs out of money?

Ferry knows his respite may be temporary. By 2021, St Wilfrid’s is projected to be in deficit to the tune of £100,000 unless further action is taken. The head is already anticipating future redundancies or having to close the school to some pupils for half a day a week.

But he knows that, for some schools, the future may look even bleaker. “I can see schools closing,” he says. “If you keep cutting, then there will come a tipping point and some schools may not be able to survive that.”

School funding crisis

Schools are not allowed to set a deficit budget without explicit permission, although a shortage of cash on its own is unlikely to result in a school closing, according to Julia Harnden, funding specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders. However, it could precipitate a chain of events that could lead to closure.

“There are a lot of schools where the money they’re getting on an annual basis is not sufficient to cover their operational costs and they’re relying on their reserves,” she says. “Many are getting to the point where they have made all the cuts they can make and reserves are running out. It is becoming more difficult; some schools feel like they’re on a knife edge.”

There are mechanisms in place so that a school would not just close when the money runs out, Harnden says. These mechanisms operate through the local authority for maintained schools, and regional schools commissioners for academies. Both involve putting in place a recovery plan, including short-term additional funding from either local or central government.

School leaders would have to show how they intended to repay the money, as well as agree changes and possibly further cuts to bring the budget back into the black, Harnden says. The recovery plan could also include exploring the option of joining a multi-academy trust, as a cushion against future financial problems.

But there is one exacerbating factor that could put a school on the path to closure.

“If a school is suffering from a falling roll, that will put their vision at risk,” says Harnden. As revenue is closely tied to the size of the school roll, a sharp drop in pupil numbers can have a devastating effect on an already struggling school.

A falling roll may be only temporary, in which case a school may need time-limited support until numbers start to rise again. But where pupil numbers are forecast to fall and keep on falling, a school’s future could be in doubt. However, even when closure is mooted, it should not go ahead without an assurance that there is sufficient capacity locally for children affected, says Harnden.

“[Closing a school] should never be a knee-jerk reaction,” she adds. “Because of the way schools have to budget and report their finances, there will be a period of time when their financial situation might be deteriorating, and it is important that everyone concerned picks up on that and starts thinking about the way forward. The mechanisms are there to make sure there is plenty of opportunity to find a satisfactory route out of any financial problems.”

But this scenario is likely to become more common as it becomes harder and harder to make cuts, says Jules White, headteacher of Tanbridge House School in West Sussex and founder of the WorthLess? grassroots school funding campaign.

“Significant and sustained financial pressures on schools are resulting in a variety of unintended consequences,” he says. “Class sizes are rising, our curricular offer is frequently diminished, and the capacity to meet a rising tide of pastoral and wellbeing challenges on behalf of students and families is at breaking point.”

One school that followed the route from financial problems to closure was Baverstock Academy in Birmingham. A falling roll and an adverse Ofsted report plunged the secondary into a spiral of decline that eventually made it financially unsustainable. Although it had capacity for 1,300 pupils, by the time it closed in the summer of 2017, it had just 419 children on roll.

“When I started, it was quite an autonomous position, but by the time I left, it was completely the opposite,” recalls Chris Czepukojć, who was head of history at Baverstock for three years.

“It was quite shocking, as a head of department, to be told that you could no longer manage your own budget.

“You had to go cap in hand to the head if you wanted to buy anything, even glue sticks. It was made very clear that the money had run out.”

While most of Baverstock’s classroom teachers were initially protected from the effects of the financial struggle, Czepukojć recalls a staff meeting in 2011 when the head spelled out the scale of the problems. Although the head said there would be no job losses - winning a round of applause - some saw the writing on the wall.

“Clearly there were problems and some people wanted to get out and started to look for jobs. It was pretty dire and it was not a happy place to work,” he says. “It put a lot of pressure on the staff and gave you a mindset that you just have to do what you can with what you’ve got. You can no longer take risks and be the sort of blue-sky-thinking teacher that most teachers want to be.”

The school eventually became part of LEAP Multi-Academy Trust, but this failed to give it financial security and, in 2016, the trust asked the government for permission to close it. “It was very sad,” says Czepukojć, who left Baverstock in 2012 and is now a deputy head at a school in Solihull. “The kids were lovely and they deserved better.”

Baverstock’s long, slow decline, rather than falling off a cliff edge, is typical of what happens when a school runs out of money, according to Stephen Morales, chief executive of the Institute of School Business Leadership. And early warning signs that a school is getting into difficulties should be picked up by either the local authority or the Education and Skills Funding Agency, which can then work with the leadership team to draw up a plan to tackle the shortfall.

“What happens next will differ from context to context, but it normally amounts to a pot of money to plug the gap and an agreed payback period,” Morales says. “Schools aren’t just left to collapse.”

Small rural schools are perhaps the most at risk. Their size makes them vulnerable to even slight fluctuations in pupil numbers, Morales explains, while isolation means they are not able to call on neighbours for support in the way that urban schools can. But there may also be political pressures to keep these rural schools open, he adds.

Clem Coady knows that he is just a leaky roof away from disaster.

As the head of Stoneraise School, a primary on the outskirts of Carlisle, he is forecast to be in the black by just £9,000 on a budget of around £500,000 in the 2019-20 financial year. But with reserves of just £11,000, there is little room for manoeuvre. He has already lost 40 hours a week of teaching assistant time and has slashed his use of supply teachers to just £8 per pupil per year. But that may not be enough, even though the roll is increasing - from 104 children last year to 117 in September. Without further cuts, the school is projected to go into deficit in three years.

“We’re hanging on by our teeth,” he says. “If English and maths results go down, we go into an Ofsted category and then it’s a spiral downwards. We’re in the black, but if we have to bring in a supply teacher or there’s a leak in the roof, that could all change. Whether we remain financially viable three or four years down the road, I don’t know.”

A deficit budget would mean that decisions over spending would be taken out of his hands, and Coady, who has been head at Stoneraise since 2011, knows his grip is already precarious. He relies on bringing in £15,000, through hiring out the school premises and releasing staff to run training in other schools.

“When I became a headteacher, my number one concern was Ofsted. Now, it doesn’t even make the top five problems,” he says. “We’re due Ofsted imminently, but if they phone in the next half-hour I wouldn’t be fussed. Funding is the only issue now.”

Nick Morrison is a freelance writer

This article originally appeared in the 12 April 2019 issue under the headline “What happens when the money runs out?”

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles