Experiments in human behaviour

On a quiet Sunday morning in the summer of 1971, a police patrol car made its way through the streets of Palo Alto, California, rounding up a group of 24 undergraduate students. The students were read their rights, handcuffed, fingerprinted and deposited, not in the local jail but in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology department and into the care of Professor Philip Zimbardo. And so began one of the most astounding and controversial experiments in the field of social psychology.

The educational press today abounds with research telling teachers what works and what doesn’t work when it comes to classroom practice. Little by little, our understanding of what make effective teaching strategies is becoming clearer as we increasingly rely on research and evidence rather than guesswork and supposition. But what can we learn from the early pioneers of social research, who, although they weren’t necessarily studying classrooms, certainly discovered a great deal about human behaviour?

In the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo asked his participants to become either prisoners or guards, hoping to discover whether people would alter their behaviour when given a specific social role to perform.

The “prisoners” soon began to show signs of frustration with their situation, and found ways to rebel, barricading themselves inside their cells and refusing to follow instructions. In response, the “guards” developed inventive ways of controlling the prisoners, including sleep deprivation, withholding food and ritual humiliation.

The whole thing went completely off the rails, with inmates suffering emotional breakdowns and demanding to be released. It was only when a graduate research student stopped by the lab to see how things were going - and was horrified by what she found - that she convinced Zimbardo to stop. The experiment was shut down 10 days into its scheduled two weeks.

When the dust had settled, Zimbardo’s conclusion was that giving people social roles makes them adopt a set of associated behaviours, and that in many cases people will commit to these behaviours with a surprising intensity.

So what can we learn from Zimbardo’s experiment, and how might it help us in the classroom? In schools, the roles of students and teachers are fixed from the moment we walk through the school gates, and they come with a set of expected behaviours. What’s more, we’re rarely aware how fiercely we commit to these roles, and so the chance to resist probably doesn’t even occur to us.

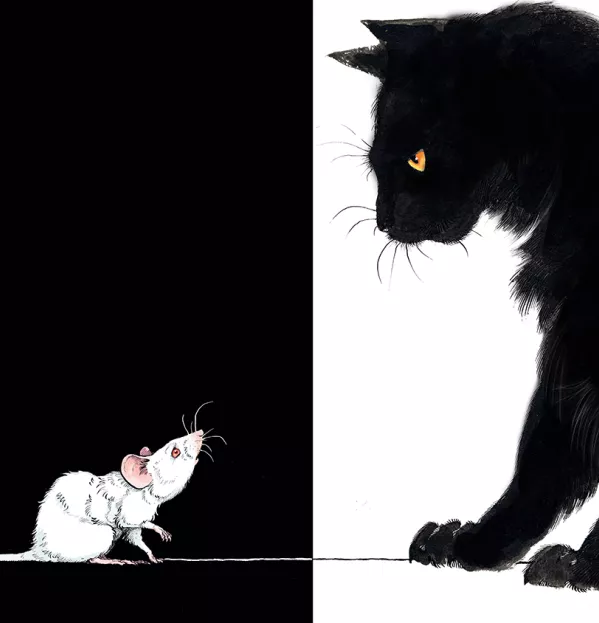

Most of the time, playing out these roles is fine: the teachers teach and the students learn. But we know it doesn’t always work like that. One of the most pernicious ways these roles affect the smooth running of a school is in the creation of an “us and them” mentality. We see it every day in school, in the classrooms and the corridors, a little more with certain teachers or certain students for sure, and sometimes in a systemic way across the whole school. The problem is that it inevitably leads to resentment on both sides, and to behaviour that can range from irritating to destructive.

Role back the years

So how does it all go wrong? In Zimbardo’s eyes, the problems stem from the pre-existing ideas we all have about certain social roles - in this case, what it means to be either a teacher or a student. In a school, as soon as a student starts to mess about or question the rules, or the moment teachers try to exert their authority, the danger is that our own ideas about how to behave go out of the classroom window and instead we start to behave in the manner our roles dictate.

Imagine this all-too-familiar scenario. A Year 9 group enters the classroom. One student, who’s a little slow to get settled, is told to take off his coat and get out his books. The student responds with a moan or a mumbled insult. The teacher raises her voice and demands compliance. The student answers back and ends up in detention, and the teacher ends up angry and rattled before she’s even had time to write the learning objectives on the board. This happens because this is how teachers and students are expected to behave. We learn these roles early on, and for most of us they become internalised to the point at which we forget that they’re roles at all.

Would we be so quick to act this way outside of such a unique situation? “Hey, Dave, can you pass the salt, please? I can’t reach it.”

“Hold on a second - let me just finish pouring myself a glass of water.”

“Didn’t you hear me? I said, pass me the salt. I need the salt right now. Pour your water in your own damn time!”

It seems unlikely. Most of the time we act rationally and with consideration. We cut people some slack. We don’t, to use the technical pedagogic language, act like dicks.

The problem that can arise in the classroom is that it’s harder to see ourselves in the place of the other, so students imagining what it’s like to be a teacher or teachers remembering what it was like to be a student. And we teachers should be doing the work here, because we’re the ones who’ve inhabited both roles. It might be a long time ago for some of us, but we’ve all had the luxury of knowing what it’s like to be a student. Students don’t know what it’s like to be a teacher. What they know about being a teacher is only what we show them.

There have been many times in my career when I’ve ended up acting in a way that was almost entirely down to the fact that I was playing out my role as a teacher, without any regard for whether what I was doing made sense or was helping anyone. On countless occasions, I’ve made a whole class miss break or lunch because I demanded total silence before I dismissed the class. Why? What kind of despotic madness was that? I didn’t need silence. OK, it’s nice when students listen, but insisting on total silence feels like exercising power for the sake of it.

Arguably the most famous piece of psychology research ever conducted is Stanley Milgram’s study into obedience to authority. In what are commonly known as the “electric shock experiments”, Milgram arranged to have a stooge hooked up to an impressive-looking but entirely non-functional electric shock contraption, and then tried to convince a group of unsuspecting participants to give massive electric shocks to a total stranger. The results were that over two-thirds did so without much complaint.

Milgram’s explanation for why ordinary individuals were easily convinced to hurt strangers is down to what he called “agentic shift”: the notion that once people give up a sense of personal responsibility to an authority figure, morality and good sense follow swiftly behind.

In schools, we force students into this position all the time, demanding that they follow instructions without question, simply because the instructions are being given by the recognised authority figure. It’s a situation that can make everyone involved uncomfortable.

What might be of interest to teachers looking to create a more productive educational climate would be to focus on the minority in Milgram’s study, who were not willing to do as they were told and so didn’t give the shocks. Milgram found that the rebels tended to have a greater sense of personal responsibility - surely exactly the kind of value we want to instil in young people.

It’s worth trying to remember this the next time a student refuses to do what they’re asked. Maybe they’ve got a good reason. OK, a lot of the time they probably are just being a pain in the arse. But maybe, sometimes, they’re just standing up for what they believe to be right.

Toy story

A few years before Phil Zimbardo started locking people in basements and Stan Milgram began forcing people to give each other electric shocks, another pioneering psychologist, Albert Bandura, was flouting ethical guidelines in the name of science by encouraging primary-school children to engage in acts of extreme violence … towards a toy doll.

The experiment involved showing a group of five- and six-year-olds a film of an adult attacking a large inflatable doll, then putting the kids in a room with a range of toys, including the doll. The children who’d seen the film were much more likely to attack the doll in the same violent manner as they’d seen the adult do than a second group of children who hadn’t first seen the film.

What Bandura demonstrated, in his series of “Bobo doll” experiments, was just how easily behaviour is influenced, sometimes simply by watching somebody else. Where previously it was thought that an individual had to experience rewards or punishments directly - a process known as operant conditioning - what Bandura showed was that simply watching other people could lead us to copy their behaviour, particularly if the models being imitated held a position of authority or social influence.

What this tells us is how vital the behaviour of teachers and managers in school is, in encouraging the behaviour we want to see in students. Every time a teacher speaks to a student in a classroom, there are 30 pairs of eyes watching and processing that encounter. Similarly, if a student behaves unkindly to another student and the behaviour isn’t challenged, the implied lesson is that the behaviour is acceptable.

The other side of this concern about copying harmful behaviour is that we can use the principle to encourage the behaviour we want to see by modelling that, too. Once we recognise that teachers are role models - and God knows it doesn’t always seem like that - then we can make sure that we steer students towards desired outcomes by showing them what we’re looking for. It’s maybe not an easy thought but, as teachers, how we talk and act is important all the time.

So what can we take away from all this research carried out in the name of gaining a better understanding of human behaviour? A lot of the findings aren’t all that surprising: if you give someone a uniform they may act like a despot; if you take away someone’s rights, they may not act responsibly; if you punch a doll and then give someone that doll, they’ll probably punch it too.

Perhaps the lesson is that we have to keep on reminding ourselves of these truths. In the maelstrom of teaching, with the constant and relentless pressures of exams and targets and inspections, sometimes we have to go back to a few important principles about how to get the best out of others, be they students or other teachers.

In educational terminology, this is often referred to as being reflexive. But, explicitly, it means looking at ourselves from time to time and checking to see that we’re being the teacher - the person - we want to be: the one who, once upon a time, set out to help kids and make a difference. And, hopefully, nobody needs to get locked in a basement.

Callum Jacobs is a supply teacher in the UK

This article originally appeared in the 18 October 2019 issue of Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters