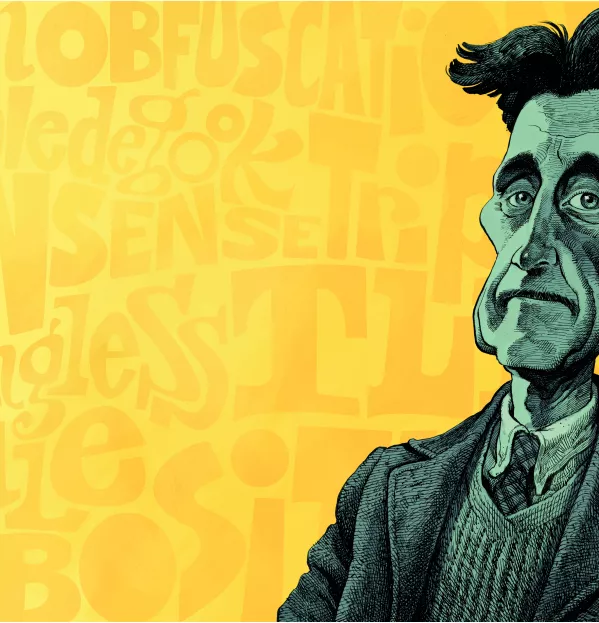

George Orwell would be left speechless by education jargon

In 1946, George Orwell published one of his best known essays, Politics and the English Language. In it, he takes aim at the sloppy use of language and the damaging effects this has on thinking. He decries the use of unnecessarily long, foreign or meaningless words, hackneyed metaphors and jargon, saying that these serve only to obscure meaning rather than reveal it (errors I fall foul of daily).

Orwell sees poor language as the product as well as the cause of foolish thinking: “It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

His point is suggestive of Wittgenstein’s oft-quoted phrase that “the limits of my language are the limits of my world”. Good prose, comments Orwell, should be “like a windowpane”. His points are instructive for anyone who seeks to be understood in written form. I can’t help thinking, however, that they may have been overlooked by the bureaucracies that govern our education system today.

I returned to this country to teach about five years ago, whereupon I was beset by the sheer number of acronyms, initialisms and abbreviations being thrown around - they were bewildering. Though alienating at first, in time I began to understand their meaning and place in the system (albeit vaguely in some cases). Education is full of such acronyms, and perhaps it is by necessity, for the sake of brevity or rhyme, or (a somewhat more cynical view) to fill a colourful wheel on a poster. Knowledge of these seems to be central for many in the sector today; I know of teachers who would spend a large proportion of interview prep time boning up on their ability to deploy them fluently.

While this raises some questions of its own, I am more concerned here with how Orwell’s points speak to the ideas these acronyms and initialisms represent. The initiatives and organisations behind these initials exist to shape and form education at the chalkface.

Without doubt, behind each of them lies a worthy and useful idea, brought into being by well-meaning administrators and educators. However, it is the ambiguous or nebulous nature of the documents they produce that would benefit from some of Orwell’s advice.

Teachers are on the receiving end of an endless stream of virtuous-sounding rhetoric about inclusion, diversity, leadership, outcomes, citizenship, challenge, broadening participation, excellence and so on. While these all sound like very worthy abstract ideas, they are hopelessly ill-defined.

Teachers, then, have to try to discern what, exactly, these terms mean in a classroom setting before figuring out what concrete evidence would actually look like for any one of these ideas.

As Orwell notes, the reading of opaque text can, at best, deliver opaque thinking - and this, I would contend, is one of the stressors in teaching right now. It is not so much the constant change (though that is extremely wearisome) as that what is being asked of teachers and pupils is often so unclear.

Let me try to illustrate this with some examples. These are from Scotland, where I teach, but are certainly replicated across the country. In much the same way as my students are asked to analyse and evaluate sources, I would like to do the same here, with the question being, “Does this convey a clear meaning?” The General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS) is the governing body of Scottish teaching. It is for the GTCS to decide what professional progress looks like and, as such, it has produced copious documents containing standards and guidelines for teachers.

Orwell that ends well?

Here is an example of some “professional actions” from a document titled Educational contexts and current debates in policy, education and practice: “Understand and explore the contexts and complexity in which teachers operate and the dynamic and complex role(s) of professionals within the educational community; actively consider and critically question the development(s) of policy in education; develop culture where learners meaningfully participate in decisions related to their learning and school; develop and apply political literacy and political insight in relation to professional practice, educational change and policy development.”

I am sure that lurking within those words is an idea worth hearing, but the noise of vague and vapid language has drowned it out. What might it mean to understand and explore the contexts and complexity? What does it mean to develop and apply political literacy and political insight in relation to professional practice? If I were using this guidance for some kind of professional review process, I would struggle to clarify what was being asked. Even if I took a good guess, it remains woefully unclear what success looks like in terms of “professional actions”.

The same document also informs us of this: “The teacher as an adaptive expert is open to change and engages with new and emerging ideas about teaching and learning within the ever-evolving curricular and pedagogical contexts in which teaching and learning takes place.” It sounds good until you think about it, whereupon the point seems to evade one’s grasp (and is somewhat redolent of Orwell’s comment that certain language seems to “give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”).

These are just two examples plucked at random from one document out of many - and they are certainly not restricted to the GTCS. Within the document, there exist a number of “professional actions” that are actually clear and actionable, and these are sweet to behold. However, clarity in these documents feels like a cold drink of water on a scorching day, which serves only to make the point that there is not enough of it. The pages of text, often duplicated in places, bring to mind Mark Twain’s famous quip in a letter to a friend that “if I’d had more time, I would have written a shorter letter”.

The same problem exists within exam boards, which teachers and pupils are hostage to. I am sure it varies between subjects, and, doubtless, hard science and maths are much easier to define content and marking instructions for. However, there is a general sense of insecurity and unease about what exactly is meant by certain standards, marking schemes and course outlines. The subject content is often brief and vague, leaving the teacher to work out what they should include.

I believe this has been done in the name of teacher autonomy, though I do not know of any teachers who wouldn’t rather be told exactly what they should be teaching and where to find information on it - the fact that many subjects lack textbooks, like those for A-level courses, serves to compound the issue.

Perhaps evidence of ambiguity can be found in the fact that there is such demand for “understanding standards” meetings. I have been to a number, and they are invariably well attended by teachers who are anxious with questions about the standards. By the end of these events, most teachers leave clearer on what the person leading the session takes the standards to mean - but not necessarily on the wording itself. The very existence of these meetings surely testifies to the fact that communication about standards and related issues is anything but clear.

How exams are marked is also far from clear. Once again, this will vary hugely - no doubt being more difficult by nature in the humanities subjects. Marks are awarded for specified skills, namely knowledge, analysis and evaluation. However, the meaning of words such as “analysis” and “evaluation” seems to vary not only between subjects but between levels within a subject. More than that, it is difficult to discern where marks are to be awarded for analysis and for evaluation.

Take an example from how some unit support notes identify analysis and evaluation: “Analysis will involve: making connections, explaining the background, predicting consequences, identifying implications, interpreting sources and viewpoints.”

Then compare this: “Evaluation will involve: making a supported judgement on an issue, making a supported measurement of the effects, impact or significance of an issue, presenting a case for or against a position, commenting on the quality of positions taken on issues.”

I find it tricky to make a useful distinction between the above guidance for analysis and evaluation. In one Higher (a Scottish qualification roughly equivalent to an A level) subject, analysis and evaluation were actually amalgamated, which seems to be a tacit admission that the distinction is anything but clear. To understand the difference between some grade brackets, one must have a clear understanding of how words such as “basic” differ from “straightforward”, or how “some evidence” differs from “glimmers of evidence”.

If teachers find it tricky to tell the difference between these areas, it’s hard to imagine that students will find much clarity here.

If Orwell is right that vague language can only give birth to vague thought, and that the two reinforce one another, then the problem will not disappear without a deliberate change in communication style.

At the end of Orwell’s essay, he gives a list of six rules for writing that should help one to communicate clearly. In a similar fashion, I would like to make five modest suggestions for those in the habit of developing educational documentation:

- Brevity: say more in fewer words, cut to the key points and do not duplicate.

- Where there is the danger of ambiguity, give clear and concrete examples.

- Have teachers proofread documents for clarity and understanding before publishing.

- Publish examination documentation before the summer.

- Send examination scripts back to schools on request.

Following these simple rules would solve many of the issues raised above and would help create an education culture where our thinking is improved, rather than muddied, by our language.

Kenneth Primrose is a philosophy and religion teacher in Scotland

This article originally appeared in the 12 April 2019 issue under the headline “The gobbledegook that we put up with would leave Orwell speechless”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters