Has the ‘big idea’ for improving Northern schools gone south?

Something must be done about school standards in the North of England. That is the clear and increasingly loud message that has been emanating from the country’s political and educational establishment.

Everyone from politicians such as George Osborne, Nick Clegg and MPs on the Commons Education Select Committee to former head of Ofsted Sir Michael Wilshaw and children’s commissioner for England Anne Longfield - and, most recently, schools minster Nick Gibb - has been putting in their two penn’orth on the subject.

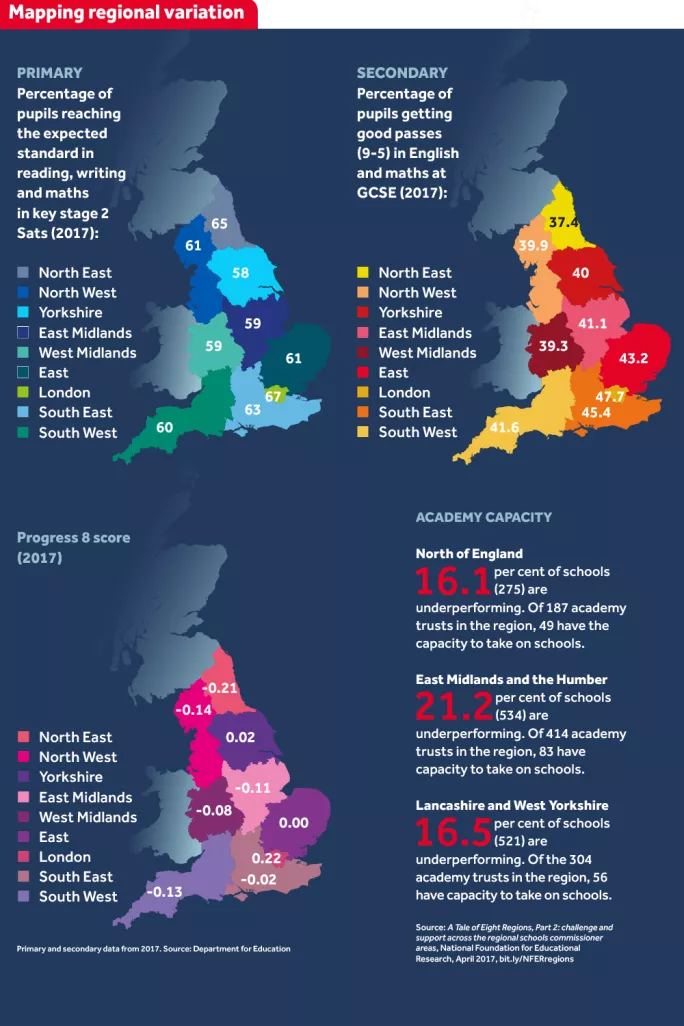

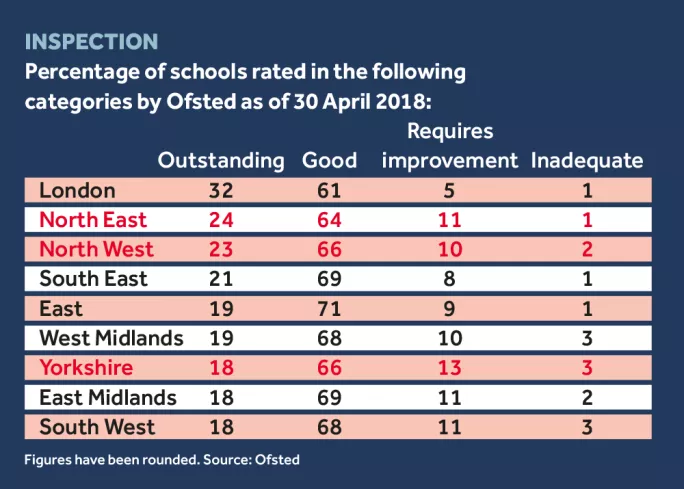

There are, of course, already well-rehearsed arguments over whether results in the North are really that bad when intakes are taken into account, and whether castigating an entire region as having “substandard” schools is actually helpful.

But put those reservations to one side for a moment. Because there is a much more immediate problem for those who back Osborne’s call last month for ministers to make raising standards in Northern schools their “big idea”. No one seems to be very sure about how to turn that commitment into real change.

Westminster has allocated tens of millions of pounds to tackling the problem but, as far as anyone can work out, only a fraction of that money has been spent. Ministers had pin-pointed academy chains that they believed could make a difference - but two of the five they named have already come to grief. Other ideas appear to have simply been ignored.

Changes at the top

Part of the problem seems to have been the recent rapid turnover in education secretaries at the Department for Education. The government has made several attempts to tackle school standards in the North since 2015, but each change at the top at Sanctuary Buildings has brought a different approach and, so far, no clear sign of success.

When he was chancellor, Osborne commissioned Sir Nick Weller, chief executive of the Bradford based Dixons academy chain, to produce a strategy. It was published in November 2016 along with the announcement of £70 million funding to support it.

But Lord O’Neill, who served as Conservative Treasury minister in 2015-16, has now cast doubt on whether those millions have actually been spent, suggesting that the education committee look into the matter.

He tells Tes: “My experience is that the government can make an announcement that money is being committed to something and then that ends up being the end of it. Until last week [when the DfE published a press release following the committee’s probing] I was not aware of any of it having been used.”

O’Neill recalls how when he attended a Northern Powerhouse education conference last year, two DfE officials speaking at the event seemed unaware of the fund’s existence.

To date, there have been no major commitments to implement the recommendations that Weller made, and the whole Northern Powerhouse schools strategy has barely been talked about since its launch.

The report identified teacher recruitment and leadership as two key themes.

Recommendations included piloting a new Teach North scheme to attract and retain talented newly qualified teachers (NQTs) in disadvantaged schools and encouraging successful academy chain chief executives in other parts of the country to mentor their counterparts in the North.

The commitment to a Northern Powerhouse schools strategy was made when Osborne was in office. By the time a report was published, he had left in the wake of the Brexit referendum. So does the initiative still have political backing or has this schools strategy been forgotten about?

O’Neill does not offer much cause for optimism. “I can understand why someone would come to that conclusion,” he says. It was on the back of his evidence that the education committee asked the DfE how much of the Northern Powerhouse fund had been spent.

The DfE insists the money is being used. A fortnight after the questions were raised, it issued a press release announcing £6 million for maths teaching, including two new hubs in the North West, as part of the Northern Powerhouse schools strategy.

The department also points to new support for parents to improve their children’s early language and literacy skills, announced by education secretary Damian Hinds and led by a £5 million Education Endowment Foundation project in the North. A series of schemes to help more children from disadvantaged backgrounds master the basics of reading was announced by his predecessor Justine Greening in January. The DfE said this was partly funded by the Northern Powerhouse money.

Yet when these schemes were publicised, the press releases made no mention of the Northern Powerhouse fund that was paying for them. And when Tes inquired, the DfE was unable to account for any more of the promised £70 million than the £11 million mentioned above.

For Osborne and O’Neill, improving education is a crucial part of building a Northern Powerhouse - connecting neighbouring cities to create a market the size of London. In O’Neill’s view, establishing the powerhouse is not just about regenerating the North but about transforming the UK. However, he suggests that not everyone in the DfE is signed up to the cause.

“I don’t think people in the DfE particularly believe in the Northern Powerhouse concept intellectually,” he says. The peer adds that they may question why there should be a focus on just one area of the country. But O’Neill is nonetheless pleased that northern school improvement is back on their agenda.

One of the main conclusions of Weller’s strategy was that academies would be central to driving up standards in the North. And despite Hinds recently announcing the scaling back of forced academisation, it seems that this remains the government’s focus.

Gibb told the education committee recently that the problem was a shortage of good academy sponsors in the North: “We need more Harrises, more Arks, more Outwood Granges.” Illustrating his own point, only one of the chains he mentioned is based in the North. Gibb says that the multi-academy trust (MAT) development and improvement fund, which the government has invited bids for, will address this.

However the government’s record at growing MAT capacity in the North has been mixed. In 2015, it gave £5 million from another pot of money, the Northern Fund, to five trusted academy chains to establish hubs of schools in areas of underperformance. Outwood Grange Academies Trust, Astrea Academy Trust and Tauheedul Education Trust have done this, taking on struggling schools in the North East, South Yorkshire and Bradford.

But the story is very different for two other recipients: Wakefield City Academies Trust (WCAT) and Bright Tribe. Between them they were given around £1.5 million. But in less than three years, both have all but disappeared from the North, having had to either abandon plans to take on more schools or give up the ones they were responsible for.

WCAT announced in September of last year that it was giving up all of its 21 schools because it did not believe it had the capacity to run them. Further controversy followed when it emerged that funds from individual school accounts had been moved out by the trust.

High Crags Primary in Shipley, West Yorkshire, was one of the schools to become engulfed in the WCAT cash row. For Mike Pollard, a governor at the school and a Conservative councillor, the events are symptomatic of a bigger problem. “The main point isn’t that WCAT is a shambles, which it undoubtedly is, but that the DfE or regional schools commissioners were so desperate to find sponsors in the North that their due diligence about WCAT was abject,” he says.

The fall of WCAT demonstrates not only the shortage of sponsors for the DfE to turn to in the North but also the difficulties of attempting to expand MATs. The director of another chain in the North with major growth plans, Frank Norris of the Co-op Academies Trust, says the DfE is nervous about the trust’s own ambition to more than treble in size because: “They don’t want another Wakefield on their hands.”

Mike Parker, the director of Schools NorthEast - the country’s only regional network of schools - says expanding MATs presents different challenges in the North to somewhere like London.

“There has been talk about the need for schools in a close geographic cluster,” he explains. “[Academies minister] Lord Agnew said you should be able to travel between schools in a MAT on your lunchbreak.”

But Parker points out that in parts of the North East, neighbouring schools might not be a natural fit, and in some cases there are no neighbouring schools. For example, the Northumberland catchment area of Haydon Bridge School is same size geographically as an area of London with 350 secondary schools.

Parker believes that for a MAT to work, you need a mix of education and business experience. And this is likely to be more readily available in economically thriving urban centres than in parts of the country that are either sparsely populated or economically deprived - or both.

Agnew has said the “sweet spot” for a MAT is to have between 12 and 20 schools catering for up to 10,000 pupils. In the North East, there are only two MATs that meet this description, but there more than 40 single academies and almost 60 trusts with one or two schools. Merging MATs or getting them to collaborate is the next obvious step.

Capacity ‘doesn’t exist’

However, Paul Brennan, a former assistant director for education for councils in Leeds and North Yorkshire, warns of areas across the North where the capacity simply doesn’t exist. “Areas that most need the best sponsors generally don’t have access to them,” he says. “This is because schools are more likely to be judged to be effective if they teach predominantly more affluent or motivated students.”

Brennan adds that this leads to sponsors being located away from the communities of greatest need. He highlights coastal communities as an example of this: “Our coastal schools face a compound of challenges and very few MATs have the capacity or expertise to fully support these schools effectively.”

Talk of a North-South divide grabs the attention of politicians and journalists alike, but the problems discussed here illustrate that the North is not simply one location with one set of challenges. The issues facing schools in inner-city Hull, Bradford, rural Cumbria or the north-east coast are all different.

The government seemed to recognise this when it created “opportunity areas”. These have been established in 12 “social mobility coldspots” where there are concerns about disadvantaged pupils’ attainment. Local independent boards help decide how to develop interventions to raise social mobility and each area gets a research school supported by the Education Endowment Foundation to analyse and share evidence of what works.

Five of the 12 areas are in the North: in Blackpool, Bradford, Doncaster, the North Yorkshire coast and Oldham. However, the programme has been criticised for not including any areas in the North East, and former Lib Dem schools minister David Laws has questioned how much impact it will have given that its £72 million funding is only for three years.

Opportunity areas were seen as Greening’s vision for promoting social mobility. But what will follow for the North under her successor Hinds? The latest announcement expected to have an impact is the next wave of free schools. The DfE has said that it aims to open new schools in areas of disadvantage that have not benefited from the programme before.

Mark Lehain, interim director of free schools charity the New Schools Network, says this will mean a focus on the North of England: “Large parts of the North fit this description, so we are busy trying to identify and support groups there that would be well-positioned to successfully open and run new schools.”

The free school programme can point to some successes in the North - such as Dixons Trinity Academy in Bradford, which was the first secondary free school in the country to be rated as “outstanding”. However, it is also clear that the creation of an autonomous school-led system and the emergence of MATs are presenting more challenges in the North than has been the case elsewhere.

In the space of just over two years, there have already been several separate attempts to tackle this. But perhaps what is needed is for the government’s approach to raising school standards in the North to last beyond the lifespan of one education secretary.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters