How one proud Scottish school is shrugging off prejudice

Utter the words “Peterhead Academy”, and you can safely predict the response: raised eyebrows, head rocking back a little, breath being sucked audibly through clenched teeth. Several teachers and pupils at the school, independently of each other, tell me of having seen this response when they say where they work or study.

“Honestly, everyone just wants to put us down,” says S6 pupil and deputy head girl Emma Andrews.

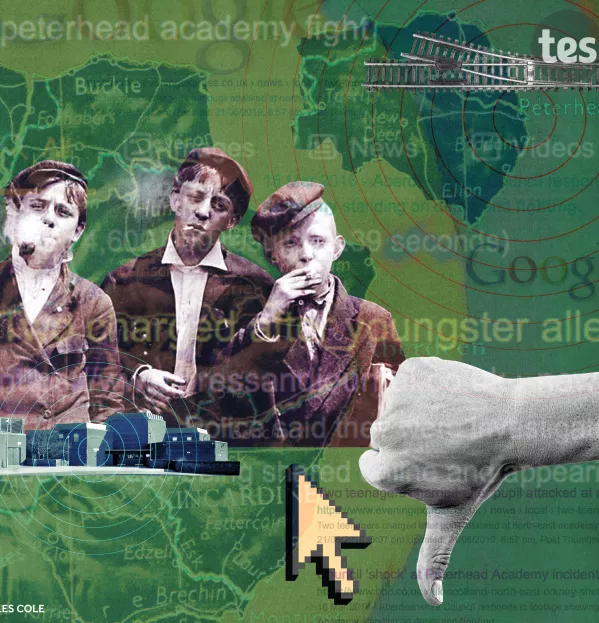

Attitudes about the school and the town of Peterhead have calcified over decades. You might trace it back more than 50 years to the Beeching cuts that lopped a huge section of Scotland off the UK rail network: what looks like a giant cat’s ear on the Scotland map became increasingly isolated from the rest of the country (see graphic, page 19).

Most people in Scotland, you can safely bet, have never been to Peterhead. It requires a big detour, even from Aberdeen and Inverness, to get there, never mind Edinburgh or Glasgow. They may well have an opinion on it, though, and often not a favourable one.

Just as the obsolete railway lines left Peterhead feeling marooned, so the decline of fishing - in a town founded by fishermen and perhaps more strongly defined by the industry than anywhere else in Scotland - chipped away at the area’s self-esteem.

Peterhead became associated with a growing drugs problem. It also made the news when inmates at the town’s prison (later a specialist prison for sex offenders, now a museum) rioted in 1987, adding to the frisson of danger associated with Peterhead.

The town’s reputation weighs heavily on the school but it also fuels staff and pupils’ efforts to establish a reputation for other, more positive, things. And attempts to boost the town’s prospects have been noticed by those in political high office, who have seen opportunities to be part of a narrative of revival. In September, the prime minister, Boris Johnson, visited Peterhead fish market as he talked up Brexit, and first minister Nicola Sturgeon toured Peterhead Academy as she revealed it would be part of a new school-building programme.

I spent time at the school prior to the visits of Johnson and Sturgeon, where I asked members of the senior management team about the first stereotypes that come to mind about the area: the words “deprivation”, “drugs” and “violence” sprang up immediately.

School reputation

All of the above have left a mark on the school (type “Peterhead Academy” into Google and the first word to come up next to it is “fight”) and they present genuine issues. But staff feel they are portrayed in a distorted way in the local media and that the advent of social media has made things even worse. The school keeps doggedly posting its successes on a Facebook page, in the knowledge that it has to be constantly monitored to counter the catcalls and baseless rumours that the online world can fuel.

But Peterhead’s geographical isolation, as well as a populace that has changed little over generations, has led to some stubborn views about the value of going to school: many pupils have left in S4 on the advice of parents who wanted them to go after a job in fishing or, in recent decades, oil and gas.

It is hard to get staff to come to Peterhead, too. Even if they get over the image problem, teachers may be put off by the logistics. Rental prices in Aberdeen, where many student teachers will have trained, for example, drive them back south before they even contemplate a 60-mile round trip up the north-east coast every day to Peterhead.

Those who do take a chance on the school, however, often stay for a long time. Most of last year’s 11 probationers have stayed on this year, and many of the staff I meet have settled in the area despite hailing from other far-flung parts of the country, where peers were often incredulous at their decision.

Guidance teacher Maureen Stout has spent her whole career at the school, and recalls the reaction at Aberdeen’s (now long gone) Northern College of Education when she announced where she was starting her career: “‘You’re not going there, are you?’ That put the fear of God into me,” she says.

Stout, however, echoes the sentiments of many of her colleagues when she says, “I absolutely love it here”.

Why is that? A common explanation seems to be that some of the challenges Peterhead Academy presents to staff may also be the key to job fulfilment that is not as easily found in many other schools.

Staff are united by a determination to broaden pupils’ horizons. You see that in the bewildering array of clubs at the school - two senior pupils tell me that however obscure your hobbies, teachers will help you start a club - as well as in how foreign trips are viewed as a central part of Peterhead Academy pupils’ education.

Some pupils might never have travelled further than Aberdeen before they end up on a trip to China or Belize. Principal technical teacher Fiona Loudoun has helped lead some of the school’s most ambitious trips through the World Challenge programme. She says the students have “a bit of spark about them” but this can dissolve quickly when they get out of their comfort zone.

Another World Challenge (and art) teacher, Kim Maxwell, says: “It’s funny because there’s a boldness within their own community, but you take them out of their community and they’re much quieter.”

PE teacher Graeme McDonald says pupils need to see that “there’s more past the A90” (which links Peterhead to Aberdeen) and that a trip to rural Central America to build toilets, cook their own meals for the first time in their lives, sleep in hammocks and bat away fist-sized insects can have a profound impact on Peterhead Academy pupils.

Community spirit

It is a common mistake, though, to imagine that people who grow up in a “deprived” area all want to flee it permanently. While “poverty” might be one of the first words outsiders equate with Peterhead, “community” comes up more often during my visit.

While that community is not a wholly positive force - many at the school say the online digs at the school and the area often come from people who live in the town - there is a bond between people in a place where many families go back generations, and people take a deep pride in helping out the school they once went to.

Helen Brown, for example, left the school in 1985. She worked as a bank manager for 20 years before retiring as a result of ill health, and now volunteers in several roles at the school, including craft sessions, mentoring and the John Muir Award for environmental projects. She also tutors pupils in maths, and last year sat and passed Advanced Higher maths - taking classes alongside 11 senior pupils - to help pupils at that level.

Biology teacher Lynne Greig also went to the school and knows all about the long grind to change its image, through her involvement in Rock Challenge. The school brought the UK-wide competition - which requires pupils to perform highly ambitious dance and drama pieces to music - about 20 years ago, and it has been key in changing perceptions. Peterhead Academy has become so good at Rock Challenge that it now bypasses the regional heats altogether, and has to turn away dozens of pupils who want to take part.

“The school gets a bad reputation but this is one of the things the community is proud of - everybody helps out, everybody chips in. People know what we’re doing - if we do a bag pack at Morrisons [opposite the school], everyone knows what it’s about.”

Greig believes there is an element of self-fulfilling prophecy to the school’s reputation, and that pupils will live down to it accordingly. After leaving school, she left Peterhead altogether, never thinking she would return - but her view of the area and its secondary school changed during her time away.

“See when you go away, you realise it’s not that bad. Peterhead is a very big village. Everyone knows everyone [and], if the community needs to band together, it will.”

Self-fulfilling prophecy

Greig says the school’s huge range of extracurricular offerings is crucial to success in the classroom, and not just because of the confidence pupils gain - it’s also about how the view of the teacher changes. If you only ever deal with a pupil who cannot fathom the difference between a stem and a stamen, and gets restless and irritable easily, goes the rationale, you may treat them differently after you have seen them shining on stage.

The school also taps into myriad local businesses to help change pupils’ views. Biology teacher Euan Burford, for example, has just started running a National Progression Award in beekeeping with the help of a local beekeeper. You never know what might click with a pupil, so you have to give them as many experiences as possible, he reasons. He hopes this course will be the springboard to biology at exam level for pupils who never thought themselves capable of that.

Helen Clements (PE), Darby King (PE) and Melissa Smart (French) were all probationers at the school last year who have decided to stay on. They talk up the strong bond between the staff, united by a determination to prove wrong the school’s naysayers. And running school clubs - in their cases, netball, cheerleading and languages - has been critical to striking up a rapport with pupils, they say.

“If you come on like a tonne of bricks with them, it just has the opposite effect [but] if you can show a bit of personality and humour, they really respond to that,” says Smart. She adds that what goes on in the club might not be particularly important - rather than reading French magazines, her denizens might simply want a relaxed escape from the school’s often cramped surroundings.

Principal teacher of English Katherine Rigby thinks back to what colleagues at her old school in Aberdeen asked when she said she was moving to Peterhead: “Have they given you danger money?”

Rigby, who is originally from Manchester and still has an accent that is more Coronation Street than Blue Toon (the nickname for Peterhead), adds: “It is really frustrating ...there’s the perception that this school is rough and full of miscreants, and it’s just not.

“We have amazing kids here. I found them a wee bit hard to get onside - it took me a while to get their trust. But once you know them and they know you, you’re fine.”

That reputation can go two ways, she says. One fork in the road leads to “people think we’re rubbish, so why even bother trying?” More common these days, though, is that they feel they’ve got something to prove, Rigby believes.

“I love working here - there’s lots of banter, lots of humour,” she says, but adds that this wit and spark can hide a lack of self-confidence in pupils. So she is helping to relaunch the pupil council to make sure everyone can get their voice heard, while the school’s work with Unicef’s Rights Respecting Schools scheme is part of an effort to make sure that Peterhead pupils know they have the same rights as anyone else - “that they’re no different to kids in Aberdeen or Glasgow”.

“I went to a private school and no one ever told me I couldn’t do something. Girls in my year wanted to work for Nasa, to be doctors, lawyers, and no one said ‘no’,” says Rigby.

“Everyone said, ‘Put your mind to it, work hard, let’s see what we can do’ - that’s the attitude that we need to get in the kids here.”

She adds, though, that the way pupils view the place where they live can be a big barrier: “Sometimes they say to me, ‘Why do you work here?’ ‘Well, I like it here,’ I say. Then it’s, ‘What do you mean you like it?’ It’s really sad.”

That frustration is shared by biology teacher Emma Tocher, who says “you won’t find a single positive thing” about the school in local media because “nobody clicks on it - it’s the negative stuff that seems to pull the readers, and most of it’s nonsense”.

But she adds that staff are “fighting from the inside to get the positives out through the kids, so the kids are going home saying, ‘Oh, I did this really good thing at school’, instead of, ‘Oh, did you see this on Facebook?’ [and]I think we’re winning”.

S6 student Shannon Christie, who wants to study medicine, leans forward to emphasise her point: “There’s very little positive online about the school - it’s so frustrating. All [people] see is ‘boys misbehaving at Morrisons’ or ‘boys running across the road’ - yeah, but there’s only five of them; the rest of us are using the crossing.”

‘Massive difference’

Christie says that headteacher Shona Sellers has made a “massive difference” in recent years by making school life more structured, uniform stricter and focusing on attendance, but that teachers’ commitment to running a wide array of activities and clubs is also worth shouting about.

“That’s kind of rubbed off on us,” says Christie, pointing to the senior pupils who now mentor younger pupils - she helps a boy with his maths in her spare time.

Senior pupils also started The Hive, a safe drop-in for younger pupils to help them make friends, which has been particularly helpful for pupils with English as an additional language, who now make up about 17 per cent of the school roll after an increase in immigrants from Eastern Europe over the past decade or so, drawn to work in the town’s fish-processing factories.

Principal teacher of literacy Chloe Cargill started at the school in February and says the Peterhead pupils’ “refreshing honesty” marks them out. She recalls one teacher who, after a haircut, was asked by a boy if he’d had it done at the place down the road, confirmed that he had, and was met with this matter-of-fact response: “Aye, they always make a mess of it.”

But “you really, really need to work hard” at building positive relationships and that sense of ease with the teacher, she says.

“They’re definitely suspicious of you, and they’ll ask, ‘How long are you going to be here?’ Here, there wasn’t an automatic, ‘Oh, you’re the teacher, I’m going to sit down and just listen to you’. I didn’t have that respect straightaway - you have to earn it.”

It can be hard but ultimately “more rewarding” than working in schools without the same challenges, says Cargill. Staff have to “really know the kids”, not just “the headline acts” who excel academically. And you can’t be “a lazy teacher”, trotting out the same lessons time after time because “I don’t think the kids would feel valued enough to want to work hard”.

In one English class before the summer holidays, pupils were asked to write a guide for a tourist coming to Peterhead. The instant, dumbfounded reaction was: “Why would they want to come here?”

In a place like Peterhead, you can, of course, improve pupils’ life prospects with high-quality teaching and a cornucopia of extracurricular opportunities. But as Cargill says, you must also show, day after day, why their community “doesn’t deserve the reputation it has”.

Change students’ mindset about their immediate world, then, and you change how they see their place in the world beyond it.

Henry Hepburn is news editor for Tes Scotland. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

This article originally appeared in the 11 October 2019 issue under the headline “Pride and prejudice”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters