Let’s put social justice at the heart of education

As a minister until recently in the Department for Education, I wasn’t allowed to use the words “social justice” - the “in words” were “social mobility”, which always had the ring of a Vodafone advert to me. But social justice, improving outcomes for those from disadvantaged backgrounds, should be at the heart of our educational system.

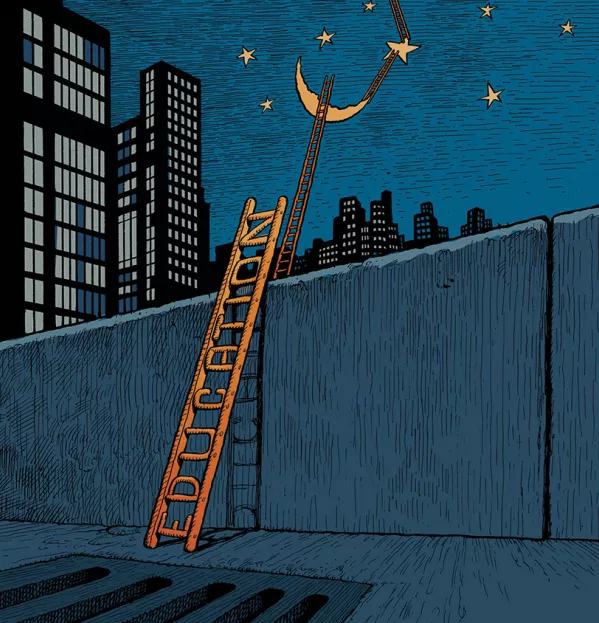

Education should offer a ladder of opportunity that gives everyone the chance to progress and access education, from early years through to adult education. In this Parliament, the goal of social justice, and that of boosting the nation’s productivity, will be central to the work of the Commons Education Select Committee, which I chair.

Ensuring that the most disadvantaged members of our society have access to quality education is a fundamental matter of social justice. Without access, it is hard to develop the knowledge and skills required to succeed. It is the most disadvantaged members of our society who are most likely to lack quality options, and the results of this inequity run throughout our educational system.

The first few years of a child’s life, including their pre-school experiences, are crucial to their prospects. But only 54 per cent of children eligible for free school meals reach a good level of development by the age of 5 (compared with 72 per cent of their better-off counterparts). At school, just 33 per cent of pupils on FSM gain five good GCSEs (including English and maths) compared with 61 per cent of their more affluent peers.

In alternative provision, on which the committee has recently launched an inquiry, the picture is even starker. Just 1.3 per cent of children taught in alternative settings get five good GCSEs. In alternative provision, we find children who have fallen out of mainstream education for a range of complex reasons, ranging from special educational needs to severe behavioural disorders and physical illness. These children have truly awful prospects and, while some providers do an excellent job in very testing conditions, the system is broken.

As a committee, we want to press the government and those in education to ensure that alternative provision is not used as a dumping ground. Support should be given to schools to intervene early and, when alternative education is considered the right choice, we need to know the decisions about where to send children are well thought through.

Early intervention

Early years education is crucial. We should be moving to a less complex system of childcare subsidies so that families can actually claim the support available. We also need greater efforts to ensure that there is genuinely affordable and high-quality childcare in the most disadvantaged areas.

Performance in our worst schools needs to improve and the system needs to do more to encourage the best leaders, teachers and multi-academy trusts to take on failing schools. As a firm supporter of apprenticeships and technical education, it will come as no surprise that I believe schools needs to up their game in their efforts to engage with employers.

If we are to deliver in improving outcomes for those from disadvantaged backgrounds, we need to ensure that our young people receive not only a quality education, but the right education to equip them to achieve in the world of work. In December 2015, nearly a third of workers did not hold suitable qualifications for their jobs. Basic skills are also far from adequate. More than a quarter (around 9 million) of all working-aged adults in England have low literacy or numeracy skills. Despite welcome efforts from government to overhaul our apprenticeships system, we currently have a workforce that struggles to meet the demands of our economy, resulting in skills shortages in many sectors.

Productivity will also be a major focus of the committee. In 2015, UK productivity was 19 percentage points below the average of the rest of the G7 countries. Since 2007, only Italy has seen weaker productivity growth than the UK among the G7. We currently lag behind our international competitors, but boosting apprenticeships and tackling our skills gaps can play a big part in meeting this challenge.

To improve the prospects of our young people, we need an education system that develops relevant and high-value skills. When the UK is competing in an increasingly fierce global skills race, this is even more important. To meet this ambition, we must transform technical education so that it results in fewer qualifications, the qualifications have genuine prestige and they hold a value that employers can recognise and trust.

Key advice

Employers must have a strong voice in determining what the qualifications look like, and these qualifications should be targeted to meet skills shortages. The government deserves credit for transforming the way that apprenticeships are funded but apprenticeship quality is an issue to which the education committee will be paying close attention.

Sound careers advice is key, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds who have less social capital. The number of young people receiving careers advice or work experience has fallen dramatically in the past 20 years, and the quality on offer is too often inadequate. Creating new opportunities for people will be worth little if they do not know they exist or how to access them.

A quality education is one of the most effective pathways out of poverty. Yet those who are disadvantaged face higher barriers to access these pathways than their more fortunate peers.

As a committee, we want to help to embed social justice in our education system. We must ensure that education is a ladder of opportunity for all people so that, no matter what their background, they can have a genuine shot at improving their lives.

Robert Halfon is chair of the Commons Education Select committee and Conservative MP for Harlow. He was minister of state for skills between July 2016 and June 2017

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters