‘Mental health first aid’ treats stigma and pupils

The first rule of mental health used to be: “You don’t talk about mental health.” For so long, poor mental health was a taboo - referred to in disparaging and stigmatising terms, or in hushed and shameful tones.

While that is changing, it’s still a topic many people feel uncomfortable discussing. At a Stirling secondary school, however, mental health is never far from the minds of staff and pupils, as any visitor will soon discover.

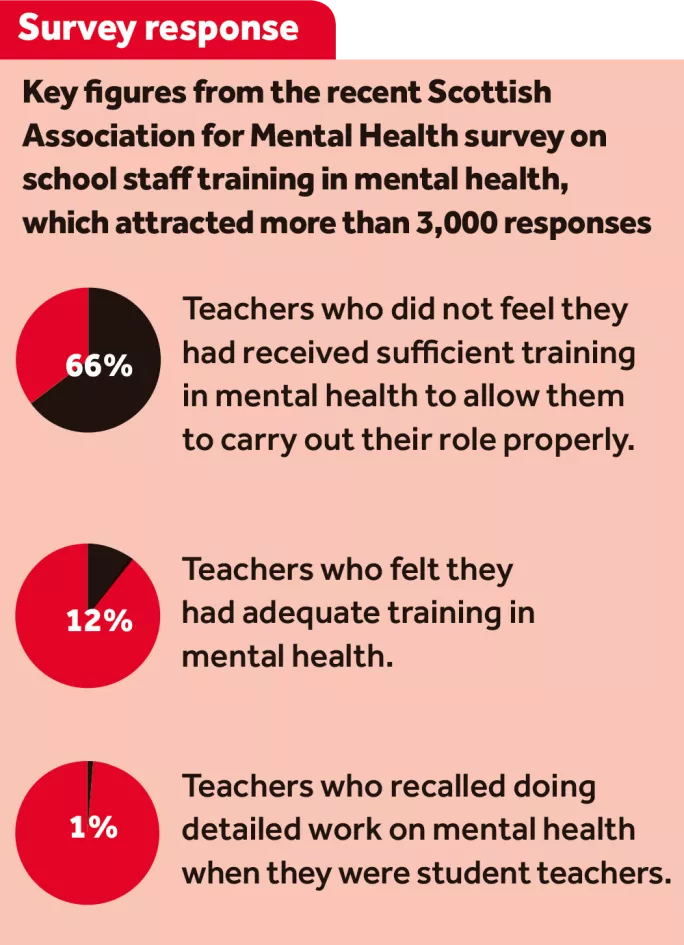

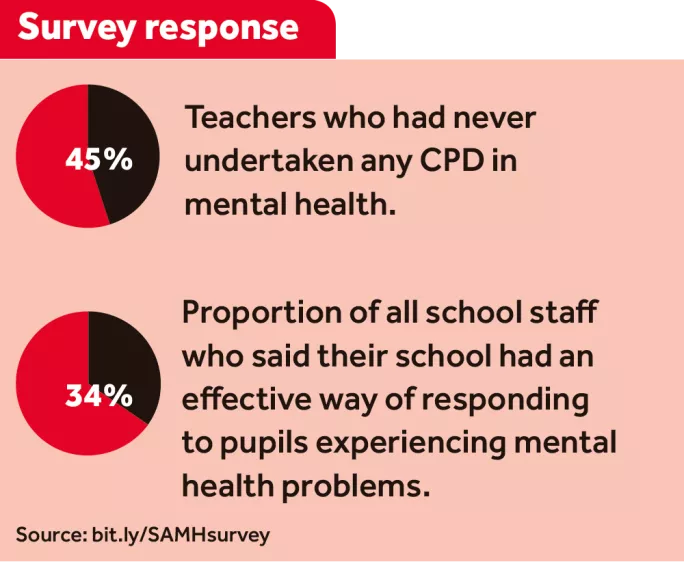

When the Scottish Association for Mental Health (SAMH) launched the findings of a survey of more than 3,000 school staff, Wallace High made the perfect venue. On that day in January, SAMH called for everyone who works in a school to receive mental health training - and at Wallace High it saw a school where everyone is already acutely aware of the importance of good mental health.

Wallace High School has 16 staff trained in “mental health first aid” by the NHS or the See Me national programme. They walk around with red lanyards, rather than the usual purple ones, as a reminder of the skills they have - and as an implicit invitation to come and have a chat.

Pam Steel - a PE teacher but also now the school’s lead teacher for mental health and the driving force behind its work in this area - says she is stopped every day by pupils who want to talk. Crucially, she says, when that happens, you have to find the time to listen.

Lucy, an S6 pupil who has had mental health difficulties, says that there have been profound changes in the school that make her far more likely to open up to teachers about her problems than in the past. “I feel like, in our school, that we are so lucky we can talk about this,” says Lucy.

In the past two years, the school has transformed its approach to mental health. Like many of the best innovations, its origins were partly fortuitous: a hip injury forced Steel off school for long periods, but she was determined not to remain idle. “I wanted something to get my teeth into,” she recalls, and there was no doubt what she wanted that to be.

“Mental health was something that I had struggled with from the age of 15,” says Steel, who left school in 1996. She had suffered from anorexia, but it was not something she ever discussed with her teachers. When the school learned of her troubles, its solution was simply to withdraw her from chemistry, a subject with which she had had particular difficulties. She never once spoke with a member of school staff about what she was going through.

Steel says she is open with pupils about her past struggles, believing that this is essential if the school wants them to feel comfortable talking about their own experiences.

Whole-school approach

Two years ago, Steel was worried about whether things had progressed very much since her schooldays. An audit of staff, pupils and parents found that, among seven areas of health and wellbeing, mental health was the one where people thought the school was doing worst - lagging way behind physical health, which scored highly.

To make a difference, she said it was essential to throw “a big blanket over the whole school - we had to go for a whole-school approach”. If you are really serious about mental health, she believes, it is not enough to tick it off in personal and social education. That said, there are imaginative classroom-based activities at the school, including S1 lessons where emojis are used to spark discussions about emotions.

The school devised an elephant logo - because mental health should not be the elephant in the room - nicknamed Elphie, which is ubiquitous at Wallace High. There is an Elphie icon on every computer desktop, for example, which will take a teacher straight to the step-by-step process for what to do if a pupil shares information about their mental health struggles. “In the past, if you told a teacher they wouldn’t know what to do,” says Steel.

Elphie is also a cuddly toy thrust upon every visitor to the school for an “Elphie selfie”, which then goes on Twitter (@WHS_HWB). The mascot has also travelled far and wide on school trips, from Edinburgh Zoo to Italian ski slopes. The idea is to produce a ripple effect out from the school, that everyone the school comes into contact with is reminded about the importance of mental health, and that stigma gradually melts away.

There is a weekly lunchtime mental health group for pupils of all ages, where members come together to talk about what the school could do to promote the issue and to help people who might be toiling. Dress-down days revolve around mental health: staff wear purple t-shirts reminding pupils to “Talk to me”.

Headteacher Scott Pennock says that without such support, pupils “are going to struggle to achieve and attain”. But there is a second, related, point, he adds: what is the point of posting good results at school “if you can’t enjoy the life you have built?”

And staff mental health is not forgotten: as well as the usual CPD, every in-service day factors in an hour-and-a-half when teachers can do whatever it is that will help them relax - the school’s way of acknowledging that downtime is essential to both good mental health and performing well at work.

Much remains to be done, believes Steel. She still sees big misunderstandings about mental health. People may not appreciate, for example, that a surge in attainment by someone suffering from anorexia is not necessarily a good sign. The biggest misconception she sees among pupils is that poor mental health leaves you unable to function: if someone who has been suicidal, for example, suddenly seems far happier, it may indicate contentment at having decided the time is right to take their own life.

Steel wants to expand the programme all the way down to nursery schools, while a group of four Wallace High pupils will soon be the first to have trained in mental health first aid, joining the 16 teachers. She also sees work to do in getting more boys involved - the lunchtime group is largely made up of girls.

For any school wanting to emulate what Wallace High is doing, Steel says there are two key ingredients: “someone with passion to drive it” and a supportive headteacher.

Wallace High’s head says all schools should be “taking a wider human view” of young people’s experiences, not just the traditional academic work of a school. For Pennock, talking about the mental health difficulties that so many people go through should be as normal as talking about exam revision.

“This is not something to be ashamed of - this is life,” he says.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters