More female staff but less equal pay - the sorry state of our schools

For a sector already drowning in data, the prospect of submitting yet more numbers to a government department may just seem like another ridiculous bureaucratic burden. Not to mention the inevitable ensuing avalanche of league tables.

“I’m sure no one rejoiced at having to file more data,” Association of School and College Leaders general secretary Geoff Barton says of the new requirement on schools to report gender pay gap data.

But far from being another dry set of numbers, the gender pay gap data returns are shaping up to create some of the most explosive spreadsheets the education sector has seen for years. Unions are even warning that the revelations could upend the female-friendly face of teaching, with some schools harbouring pay gaps way above the national average.

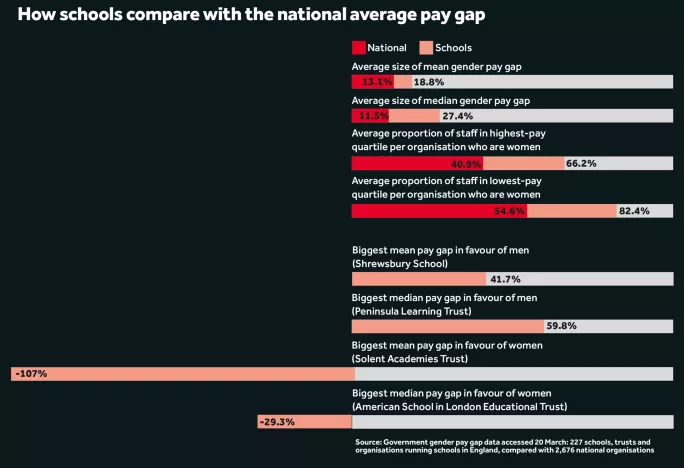

A Tes analysis of the first 227 school and academy trust returns shows that the average of the mean pay gap is 18.8 per cent - notably larger than the national mean gap average of 13.1 per cent from the 2,676 organisations that had reported by 20 March. The mean pay gap is reported as a positive number if men are paid more; a mean pay gap of 10 per cent indicates that women’s average hourly rate is 10 per cent lower than that of men.

The median pay gap - the gap between the midpoint of men’s wages and the midpoint of women’s wages - is even more stark. The average of the median pay gaps was 27.4 per cent, from those schools that had reported by 20 March; that compares with a national average of an 11.5 per cent median gap of all organisations that had reported by that time.

Polarised picture

“It reminds us that schools are a microcosm of society,” says Barton. “This data does not just cover teaching staff, but all staff, including people who are cleaning, the dinner ladies and the teaching assistants. There is encouraging news about women in leadership - and that ought to spur us on to do everything we can for the future, to demonstrate to young people that young women should be aspiring to do as well as they can, just as young men should be.”

The data is “encouraging” in that it also shows how schools differ from society in general. In education, the proportion of staff in the top quartile of their school’s pay range who are women averages 66.2 per cent - compared with 40.9 per cent across the country. But, on average, the proportion of staff in the lowest-paying quarter of jobs in their school who are women is a staggering 82.4 per cent, compared with a national average of 54.6 per cent. Why, then, is the sector so polarised?

The key fact is that while men and women may be paid equally for the same roles, women make up the majority of staff in lower-paid jobs, such as cleaners, support staff and TAs.

Department for Education school workforce data for 2016 shows that 91 per cent of TAs, 82 per cent of support staff and 75 per cent of auxiliary staff are women.

“The gap shows how feminised the school workforce is,” says Valentine Mulholland, head of policy at the National Association of Head Teachers. “It’s quite rare, apart from facilities staff, to have men in those support roles.”

But while the new data will tell us much about pay in England, Scotland and Wales, it is also important to look at what it doesn’t show. Schools and academy trusts must, like all employers, report gender pay gap figures - but only if they have at least 250 employees. So the data won’t show gender pay gaps in schools with fewer than 250 staff, unless they are part of a trust that has more than 250 employees - and even then, pay gaps in individual schools will not be discernible.

‘Difficult to compare’

This means, at primary level, hundreds if not thousands of maintained schools will not need to report, and at secondary level, many academies will be subsumed within their trust’s figures. Those two factors can create problems for anyone wanting to do an accurate comparison between the academy and maintained sectors.

“It gives us an indication, but it is difficult to compare the gender pay gap in academies and in maintained schools,” says Sandra Bennett, principal officer in the NEU union’s employment and equal rights team.

The comparison is of interest to unions, as the national workforce data shows that the average salary for all teachers in primary maintained schools is higher than it is in primary academies - and, similarly, average pay is higher in maintained secondary schools than in secondary academies.

The new data also fails to reveal whether women and men are being paid different rates for the same job. Under the 2010 Equality Act, women and men have the right to equal pay for equal work - and a successful claim showing that this is not happening can result in compensation of up to six years’ back pay.

Trusts and schools reporting their gender pay gap data invariably stress that they are meeting legal requirements on equal pay. But even if men and women are being paid equally according to the law, if more men are being employed in top jobs and more women are on low pay rates, then this will show up as an overall gender pay gap.

A lack of career progression for women can be another factor behind a gender pay gap. The independent Shrewsbury School, which has a mean pay gap of 41.7 per cent - the highest of the schools that reported by 20 March - has acknowledged the problem.

The famous public school’s report reads: “The school is committed to closing the gender pay gap…The organisation is keen to promote the recruitment and development of more female employees into senior management and teaching roles.”

The school needs to: just 22.8 per cent of the top-quartile-paying jobs at Shrewsbury are taken by women.

But having a high percentage of women in top positions is not necessarily enough to close the gap. Tes’ analysis of the first 227 schools to report shows that in 205 of them, women make up at least half of the top-earning staff. But that does not prevent an average gender pay gap of nearly 19 per cent.

Moreover, making up half of the top-earners total is not necessarily a great leap forward when you consider that about three-quarters of teachers are women.

“Women are promoted - but not in proportion to their numbers,” says Bennett.

And even in a trust in which all of the highly paid staff are women - such as the Truro and Penwith Academy Trust, which runs 20 schools in Cornwall - there can still be a pay gap in favour of men. The trust’s return shows that women’s pay is on average 27.3 per cent lower than men’s, with the median gap standing at 43.5 per cent.

While the gender pay gap figures might make depressing reading, they could prove very helpful to teachers who are likely to encounter more individual salary negotiations following the end of national pay scales and the increase in performance-related pay.

“We will be using this data in local negotiations on pay progression for teachers - it can be very difficult to get that information out of a multi-academy trust (MAT), so this is helpful. It is a step in the right direction,” says Bennett.

But what can the data do for the legions of poorly paid, largely female school staff at the bottom of the pay scale, who are the foundation of schools’ gender pay gaps?

Jon Richards, head of education at Unison, warns that the true picture could be even worse than the data suggests, as many low-paid female workers are left out of the statistics because they are employed by contractors rather than the school itself.

“These figures would be even more skewed if the vast majority of cleaning and catering staff in schools were in them,” he says. “We think there is a justification for people who are working regularly in an environment to be taken into account in these figures.”

Society’s problem?

But could the pay gap created by largely female low-paid staff have more to do with the way in which society as a whole organises itself rather than decisions taken by schools? Some academy trusts point out that many women choose lower-paid roles because they are often part-time and can be fitted around caring responsibilities.

“The higher population of women in support roles is very often an outcome of people choosing to work around having and caring for children,” Paul Walker, CEO of First Federation, a MAT of primary schools in Devon, says in a statement to Tes. “Men hold under 10 per cent of the roles in the lower quartile; the directors have noted that there are very few applicants for these roles.”

The DfE itself has recently recognised the importance of variable hours by launching a drive to encourage schools to embrace flexible working, a move designed to make teaching more attractive.

But part-time work comes at a price. Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies earlier this year noted that part-time work “shuts down wage progression”. It found that while people in paid work, in general, see their pay rise year on year as they gain experience, part-time workers tend to miss out on these gains.

Potential reasons suggested by the study included part-time workers receiving less training, missing out on networking, as well as the constraints placed on the accumulation of skills in fewer hours. So, if the current pattern of part-timers being mostly women were to continue, then greater opportunities for flexible working could actually widen the gender pay gap.

It does not have to be that way. If more men felt able to ask for fewer hours at work to spend more time with their children, and opportunities to keep part-timers on the career track were improved, then the gap could even start to close.

Employers can also make a difference - the Nonsuch and Wallington academy trust in Sutton, London, has managed to record a mean gender pay gap of just 2 per cent, partly by ensuring flexible working does not affect women’s promotion prospects and pay.

“We haven’t stopped people getting to senior positions when they have a family,” says chief executive Jane Burton.

“Typically, they will work four days [a week]. Because we’re all about girls’ education, it would be foolish of us to turn around and say to our own staff, ‘We’re not going to support you.’”

But if the overall gap does remain in schools, the warnings are that it could have a very damaging effect. “If it looks like there is a wider pay gap in teaching than in other professions, it could put women off teaching,” says Bennett.

The signs that women may be becoming disillusioned with teaching are already there to see. Ucas data shows that the proportion of 22-year-old women applying for teaching roles dropped by 16 per cent between 2014 and 2016, while the numbers of men stayed stable.

The hope is that things will change now that the data has been published, in particular for school support staff. “It’s not complete information as far as we’re concerned,” says Richards. “But it’s very useful and gives us a really strong pointer, and hopefully will make employers change their behaviour.”

Some schools may choose to focus on developing and enhancing women’s career prospects, while others may seek to ensure lower-paid staff are properly valued. Either way, Barton is optimistic: “If what we’re doing by gathering this data and learning from it means we can reinvent the profession in positive ways, that has to be a good thing.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters