Offer pupils CBT to assuage anxiety, psychologists say

Psychologists have called for all schools to offer cognitive behavioural therapy to pupils, claiming that it is the best way to tackle the rise in mental health problems.

They argue that this is preferable to prime minister Theresa May’s “kneejerk” proposal of extra training for teachers.

Leading members of the British Psychological Society (BPS) have said that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been shown to be particularly effective in tackling depression and anxiety - two of the biggest problems facing pupils today.

“Depression, anxiety and self-harm are the key topics that heads bring up when asked about their concerns,” said educational psychologist Julia Hardy, who has written a report for the BPS on how best to treat mental health problems in pupils. “The evidence base for CBT shows it’s particularly useful for anxiety. Depression as well.”

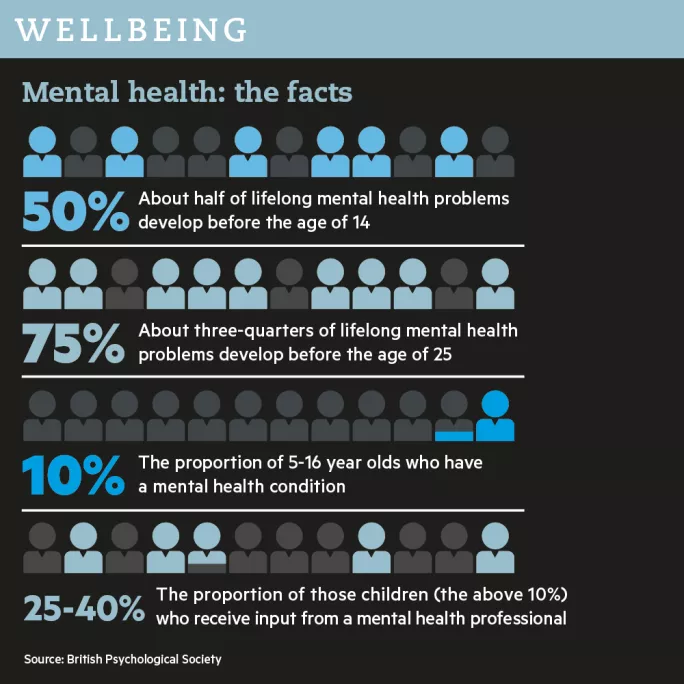

About 50 per cent of all lifelong mental health problems develop before the age of 14, and 75 per cent do so before the age of 25. Ten per cent of pupils between the ages of 5 and 16 have mental health conditions.

‘Depression, anxiety and self-harm are the key topics that heads bring up when asked about their concerns’

Last week, Ms May laid out her plans to tackle mental health problems in schools. She pledged to provide what she referred to as “mental health first aid” training for all secondary teachers within the next three years.

But teaching unions warned that funding cuts to schools and local authorities had taken a toll on the support available for any children who teachers identified as having mental health difficulties.

“There’s a huge level of unmet need,” said Vivian Hill, chair of the BPS’ division of educational and child psychology, told TES this week. “Child and adolescent mental health services have reached crisis point - there can be anything up to a one-year wait for access. Even if schools make a referral, nothing is going to happen for a very long time.”

At the moment, CBT is available to pupils only if they are referred to external mental health services. However, Ms Hill said, almost all educational psychologists are trained in delivering CBT, and would easily be able to provide the service in schools. “It would meet needs at an earlier stage,” she said.

Offering CBT on school premises would come with additional benefits, she added, citing the case of a boy she worked with as an educational psychologist who was suffering from anxiety about school lunches. Ms Hill was able to help him to conquer his fears within the school environment. “Instead of going off to a clinic, you can look at a problem in the context in which it occurs,” she said.

Exploiting existing expertise

Dr Hardy and Ms Hill were both speaking at a BPS conference of child and educational psychologists, held last week. Dr Hardy’s report, Delivering Psychological Therapies in Schools and Communities, argues that the government should use existing educational psychologists to deliver CBT to all schools.

And Ms Hill believes this option would be preferable to Ms May’s suggestion of training one teacher in every secondary to tackle mental ill health. “The government has a workforce of educational psychologists: these professionals are already in existence,” she said. “What we’re saying is that the government should look at the systems already in place, and think about how you might enhance them, rather than coming up with a political sound bite.”

Ms Hill further dismissed Ms May’s suggestions as a “kneejerk reaction to get headlines”. She said: “I think everyone has forgotten that teachers are feeling completely overwhelmed with just the classroom and managing the curriculum. It’s unreasonable to ask our already pressurised and overstressed teachers somehow magically to be able to make mental health judgement calls, too.”

BPS members insist that, while teachers have a valid role to play in helping children to manage issues such as bullying or exam stress, they can’t do the work of trained psychologists.

A government spokesperson said: “The mental health first aid training we are offering to schools will boost knowledge among teachers, but of course we recognise that teachers are not specialists and need extra support.

“That is why we are also building links with children and young people’s mental health services - extending our pilot joint training programme for healthcare professionals to cover up to 1200 more schools and colleges. We are also conducting a large-scale survey of mental health support provided in schools.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters