Pulling together to give children a better chance of school success

One weekend, sometime in the mid-1990s, I took a bus from my home in Aberdeen back to Glasgow, where I was a student. The driver was hurtling along the motorway way too fast. At some point he must have realised that he was going to reach Buchanan Street Station well before his official arrival slot - so he decided to waste some time with an unscheduled detour through the housing schemes of Glasgow’s East End.

The places our errant driver took us past were like nothing I’d seen before. There were poverty-stricken places in Aberdeen, but nothing on this scale. Multitudes of windows were covered in scabrous metal sheeting; wastelands of lank grass, strewn with white goods and furniture, were overshadowed by decaying tower blocks. The visceral sense of sprawling poverty was a shock that I recall vividly more than 20 years later.

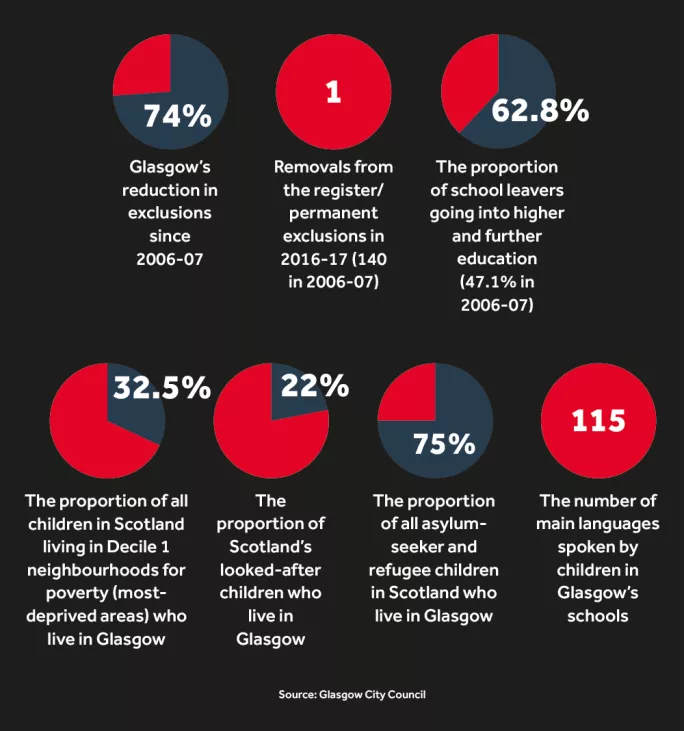

The grinding poverty long associated with Glasgow has, for many years, been blamed for attainment rates that lag behind other parts of Scotland. But something has been happening lately: year after year, Glasgow’s numbers have moved upwards. There are double the S5s gaining Highers compared to a decade ago, for example. Such trends are emerging amid a population like no other in Scotland: aside from the endemic effects of generational poverty, Glasgow has newer challenges, such as supporting three-quarters of all asylum-seeker and refugee children in Scotland.

‘Well-chosen priorities’

So what has happened? For Glasgow education director Maureen McKenna, low attainment was partly a self-fulfilling prophesy in the past, when, she says, it was not uncommon to hear senior council figures dismiss attempts to break the city’s educational “glass ceiling” with pessimistic predictions that it “won’t happen in Glasgow”.

Figures released this month, however, show 53.5 per cent of S5 pupils finishing S5 with at least one Higher, up from 26 per cent in 2006. Similarly, S5s are more than twice as likely to gain five Highers than in 2006.

Crucial, says McKenna, has been the city’s decision to select a “small number of wellchosen priorities and drive them consistently year after year” - six to start with, now four.

This includes helping Glasgow become a “nurturing city”, which, McKenna explains, is not a “soft and fluffy aspiration” but instead a declaration of intent that, unlike previous generations, no child should fall through cracks in the education system; notably, permanent exclusions are almost unheard of in 2017.

McKenna reels off examples of the impact of the Glasgow approach, whether the first member of the city’s large Roma community to attain a Higher - a Shawlands Academy pupil who got a B in music - or the 16-year-old boy at a special school whose mum died, leaving him with no other family. The school helped him keep his tenancy and complete a hospitality course, so that he could cook for himself. Now, he has a permanent catering job at the City Chambers.

“A lovely young man, but how different the story could have been without the support of his school,” says McKenna.

John Dickie, director of the Child Poverty Action Group in Scotland, has been encouraged by Glasgow schools’ attempts to drive down the cost of school - including uniforms and trips - and a growing network of teacher “champions” who share ideas on how to make school financially accessible for all.

“Much has been achieved but more still needed to ensure coming from a low-income background doesn’t act as a barrier to any aspect of the school day,” says Dickie.

Susan Quinn, the EIS teaching union’s Glasgow secretary, says that the city has struck a balance between giving schools freedom to innovate - she cites schemes such as a young mums’ unit at Smithycroft Secondary School in the East End - while retaining the reassurance that they have central support.

That chimes with Maura McNeil, headteacher at Hyndland Secondary School, which is in the leafy West End but draws 30 per cent of pupils from areas in the two highest levels of poverty.

For McNeil, Glasgow’s improvement is “dead easy” to explain: “It’s strong leadership and clear, clear expectations.” But headteachers are left to decide on methods “bespoke to our community”; she believes the greater autonomy for schools envisaged by the recent Education Governance Review is already happening in Glasgow.

Glasgow heads are also using data on deprivation and special needs to target support for pupils in a way not possible even a decade ago, says McNeil. They are “very good at sharing information” with each other - echoing educationalist Steve Munby, who said at last week’s Scottish Learning Festival that heads should “love” other schools, not only their own.

McNeil says that staff “go the extra mile for pupils all the time”, citing “Pizza Pi” - three-hour study sessions on Friday evenings for maths students who felt that an hour after school was not enough. Hyndland has also used funds from the Scottish Attainment Challenge to appoint a principal teacher charged with raising attainment in all subjects and overseeing individual plans for pupils who might be “overwhelmed by school”.

Changing lives

Of Hyndland’s encouraging attainment statistics, McNeil is most pleased about the rise in S5s with one or more Highers, from 39 per cent in 2006 to 79.6 per cent in 2017.

“That opens doors in terms of college courses and gives them belief - a lot of them come back and think, ‘Well, I’ve got one, I can get another couple’…that will change lives,” she says.

The University of Glasgow’s Professor Chris Chapman - co-director of What Works Scotland, an initiative to improve Scotland’s public services - says the city’s “significant progress in improving the outcomes of young people” is down to “an evidence-based approach focusing on three key areas”.

Firstly, it champions learning and teaching that helps all children succeed “irrespective of where they come from”; secondly, it concentrates on improving leadership among teachers and beyond; and thirdly, it invests time in working with families and communities through, for example, extensive breakfast and holiday clubs.

But Professor Chapman warns that Glasgow’s gains are “hard won” and “sometimes difficult to sustain”. To build upon the fragile successes of recent years, he predicts, it will take another big heave to create “even stronger relationships across services” and connect “all families and communities into schools systematically”.

McKenna, however, is only looking upwards. She has, for example, her sights set on Glasgow catching the national figure for S5s with one or more Higher, currently 59.7 per cent. “Only six points’ difference,” she says. That’s a big jump - but a decade ago it was twice the size.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles