RF Mackenzie: a head who helped change the face of education

Although largely forgotten by those working in Scottish schools today, the half-century-old ideas of the pioneering educationalist R F Mackenzie continue to have resonance in our classrooms.

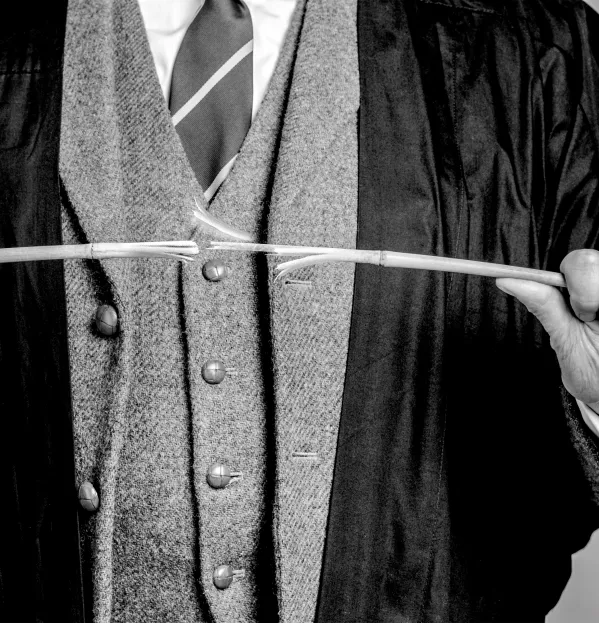

He is, perhaps, most renowned for his time at Summerhill Academy in Aberdeen in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His refusal to sanction corporal punishment at a point when the use of the tawse was the main disciplinary method in Scottish schools led to a divided staff and, ultimately, his suspension and sacking at a hearing in front of the Aberdeen Education Committee (AEC).

The public meeting with the AEC was widely reported in the national press, with then education correspondent for The Scotsman (and future editor of The Herald) Harry Reid describing Mackenzie’s contribution as “by far the most noble and dramatic speech I ever heard. It was worthy of Martin Luther King.”

At one point in proceedings, Mackenzie said it was comprehensive education itself that was on trial. And the phrase he used - “you have given us children with wounds in their souls” - still rings clear in a time when increasing emphasis is being placed on the recognition of trauma and how it influences our pupils in the classroom.

Ultimately, his views on corporal punishment were vindicated, with most Scottish councils abolishing its use in the early 1980s, a nationwide ban in state schools being instigated in 1987 and the independent sector following suit in 1998.

However, while the battle with the AEC and the staff of Summerhill was probably the most high-profile of Mackenzie’s initiatives to change the education system and - using the language of the 21st century - to improve the life chances of vulnerable pupils, it was not the only one. His concentration on interdisciplinary learning, the use of experiences to develop knowledge and vocational education complementing the academic have many parallels in the way we approach Curriculum for Excellence and Developing the Young Workforce (DYW) today.

In 1957, Mackenzie was appointed as the headteacher of Braehead Junior Secondary School in Buckhaven, Fife, and it was here that he started to put into practice the ideas he had developed about a broad education. Based partly on his experience of travelling in more liberated societies than the UK was at the time, his approach was also influenced by his serving in the RAF in the Second World War alongside “uneducated” working-class servicemen. They had been failed, as he saw it, by an education system that had taught them knowledge of little relevance to their lives but whose potential allowed them to thrive in the highly skilled work they were required to do in wartime.

He began by allowing parity between subjects that were creative and practical (including art, music and technical subjects) and more academic ones, and generated an atmosphere in which problem-solving was key. He encouraged interdisciplinary approaches, which we have only recently begun to revisit as an acceptable way to educate our children.

The tide turns

Frustrated, for example, by a mariners’ organisation that came into the school to teach navigation from a textbook - while just offshore was one of the country’s major shipping channels - Mackenzie gave freedom to the technical department to repair and rebuild old skiffs donated by local fishermen.

Then, working with the geography department, the pupils launched the boats in the Firth of Forth and figured out important lessons in seamanship, construction, weather, wind and tide. Several female pupils were involved at a time when it was almost unheard of for girls to be seen anywhere near a typical school’s “techie” department.

I can see the same approach in my own school, with collaboration between the physics and technical departments as pupils build a go-kart based on a chassis donated by a local business. It has taken almost 60 years but the DYW agenda and the embedding of the Career Management Standards have at last caught up with what was happening in Braehead decades ago.

There were many similar examples of departments working together and improving vocational as well as academic skills, but perhaps the most striking initiative was in the field of outdoor education.

Mackenzie appointed Hamish Brown (later to become a world-famous mountaineer and the first person to walk all the Munros in a single trip) as perhaps the first school-based outdoor educator in the UK. He then acquired an old shooting lodge near Fort William. Over five years, it was used for multiple trips for pupils from the “Coal Town” - Buckhaven was a mining town to the extent that coal waste blackened its beaches - who would visit, cook for themselves, sleep out in the open and walk the hills.

As Brown points out, the curriculum was determined by “locality and weather, [so] …if we found a dead deer it was dissected; biology” and “before sailing to Iona and Mull, stores were dealt with by the boys; arithmetic”.

According to Education Scotland, all pupils should have the opportunity to engage in at least one residential experience during secondary school. Every year, we take our whole S1 cohort to an outdoor centre to take part in similar activities to those experienced by the Braehead pupils 60 years ago.

Our risk assessments are tighter and the paperwork in general is considerably more complex. But without the groundbreaking work initiated by Mackenzie so long ago, I wonder, would we be in the situation where such an endeavour is commonplace for pupils from areas of multiple deprivation?

Mackenzie’s ideas, however, were not just limited to his interactions with pupils. Some of his comments, published posthumously (he died in 1987), show remarkable foresight into the way we now aim to engage parents.

In an article from the Scottish Review, published in 2004, Mackenzie outlined how we could bring parents into the classroom to help us educate their children: “One way …is to tell us what they missed at school, the information, skills and experience that would have been valuable to them in later life.”

These are fine ideas that may help to drive forward school improvement in ways now advocated by official guidance. Indeed, Mackenzie goes on to outline how parents should help to frame the policy and organise the practical affairs of a school. While this is now a standard requirement of the school improvement planning process, Mackenzie argued it would be a first step in a participative democracy that would enable all adults to become involved in running the country.

‘Common-sense solutions’

These comments, in particular, resonate in 2019: “The country will be better off when the majority contribute their common sense to the solution of problems that have hitherto baffled the minority”. That, of course, is particularly poignant given the current state of our increasingly polarised political system.

Finally, it is worth noting Mackenzie’s views on the examination system. While strides have been made over the past few years in improving how we assess our children, the principles and concepts of CfE are still held back by the need for teachers to prepare pupils for the endpoint of exams. An advocate for continuous assessment, Mackenzie decried the fact that “the memorisation of information [was] to be the core work of Scottish schools”. The exam system perpetuated an elitist view of education, he argued, especially with league tables determining what was, and wasn’t, a “good” school.

In particular, according to Peter Murphy, a former head and one of Mackenzie’s teachers, the educationalist believed the system “inhibits enquiry, it inspires boredom; it impedes experiment and progress; it enslaves the curriculum; it ignores real values; it measures useless information; it ignores character”. It would, perhaps, be difficult to argue that this assessment is less relevant today than it was 50 years ago.

So, while many of the ideas Mackenzie brought to education have been adopted and developed down the years - particularly but not exclusively by those of us working in areas of multiple deprivation - there are still more ways we could take inspiration from his words. A further reformation of the exam system would be a good place to start.

Mackenzie thought we needed to free teachers from the “task of making pupils accumulate information and memorise accepted opinions”. I hope that we have moved away from the latter point and now do more to encourage informed thought and debate. With further freedom it may be that Mackenzie’s vision of teachers becoming “changed people when presented with the opportunity to do original work” will come to fruition. In the empowered regime envisaged for the Scottish education system, perhaps we shall see just what advances such freedoms can bring for our pupils.

John Rutter is head of Inverness High School

This article originally appeared in the 9 August 2019 issue under the headline “A head of his time”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters