The rise and fall of the textbook

In recent years, teachers have been told in no uncertain terms that they should be using more textbooks, in line with the world’s top-performing education systems.

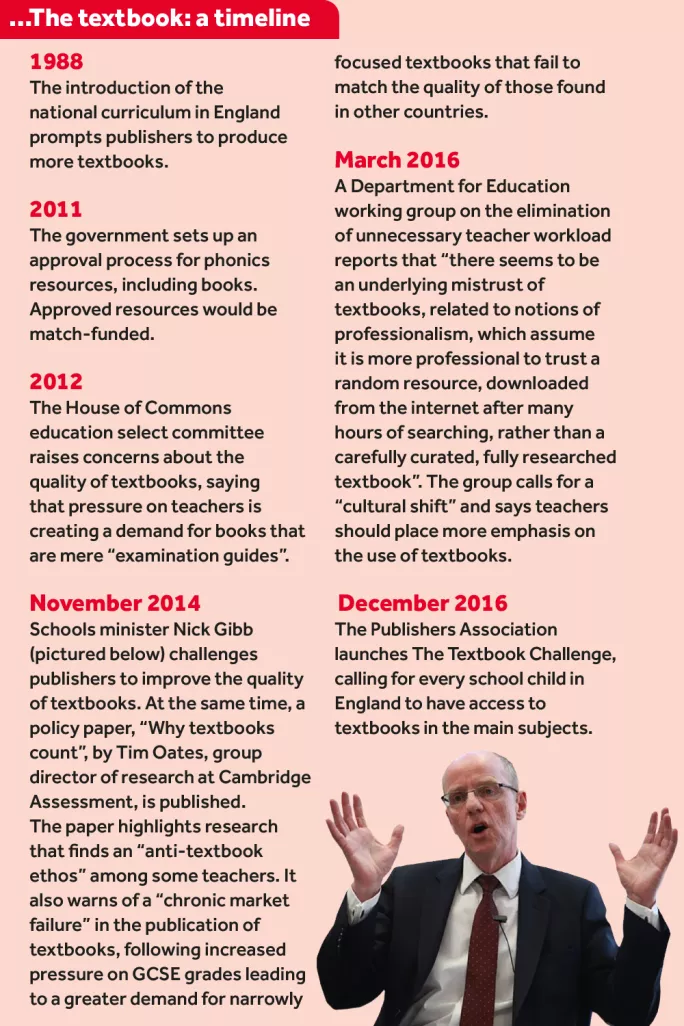

Schools minister Nick Gibb has railed against an “anti-textbook ethos” in the profession, and the government has provided match-funding aimed at increasing the use of textbooks in the classroom.

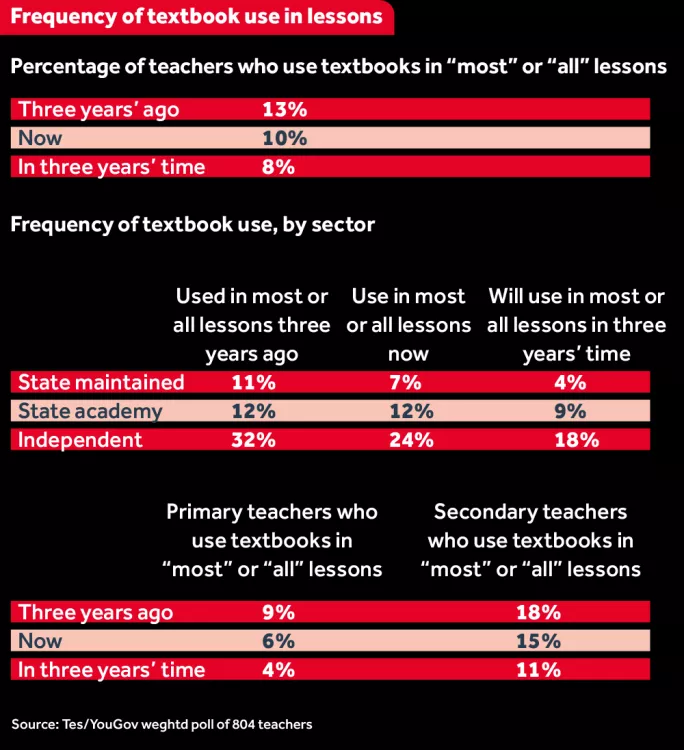

But a Tes-YouGov survey reveals teachers are heading in the opposite direction. One in 10 teachers say they use textbooks in more than half of their lessons - a drop from 13 per cent three years ago. And just 8 per cent of those surveyed think they will be using textbooks in most or all of their lessons by 2020.

Plummeting down the priority list

A major reason for the declining use of textbooks appears to be their cost.

“The squeeze on budgets and the prohibitive cost of many textbooks has deterred some heads of maths from purchasing new class sets to support delivery of the 9-1 GCSE and reformed A levels,” says David Miles, spokesman for the Mathematical Association.

“It is a huge expense to buy textbooks for key stage 4,” agrees Jo Morgan, acting head of maths at Glyn School, Surrey. “Schools didn’t feel the need to buy them for the new GCSE when they could get plenty online.”

Earlier this year, the NUT and ATL teaching unions - which have since merged to form the NEU - revealed that 73 per cent of their surveyed members said their school had cut spending on books and equipment.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, highlights the stark financial choices facing many schools.

“If a headteacher has a deficit of £175,000, the only way to reduce it is to reduce staff,” he says. “To say ‘we are going to continue to buy textbooks while we make people redundant’ would show a warped set of priorities, I think.

“In the list of difficult decisions to be made, the replenishment of textbooks would be lower down than keeping teachers and teaching assistants in the classroom.”

Tim Oates, director of research and development at Cambridge Assessment and author of the influential “Why textbooks count” policy paper, acknowledges that funding is a problem. But he says that cost is not the only reason why textbooks may be falling out of favour in schools.

Oates believes that there is still a strong anti-textbook bias in the profession amid a trend towards digital resources [note: Tes’ parent company produces digital resources for schools, although Tes editorial operates independently].

Figures from the Publishers Association also show a drop in demand for textbooks. In 2013, 21.2 million units were sold, but the total fell to 20.5m in 2016. “I think [the decline in sales] can be explained by pressure on the educational budget,” says Stephen Lotinga, chief executive of the Publishers Association.

In July, the British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA) published its latest forecast showing that spending on resources, including textbooks, had fallen by 5.5 per cent between 2016 and 2017.

It estimated that secondary schools had slashed their budgets for resources by an average of £17,030 over that period, while primary schools had cut their spending on resources by £3,750.

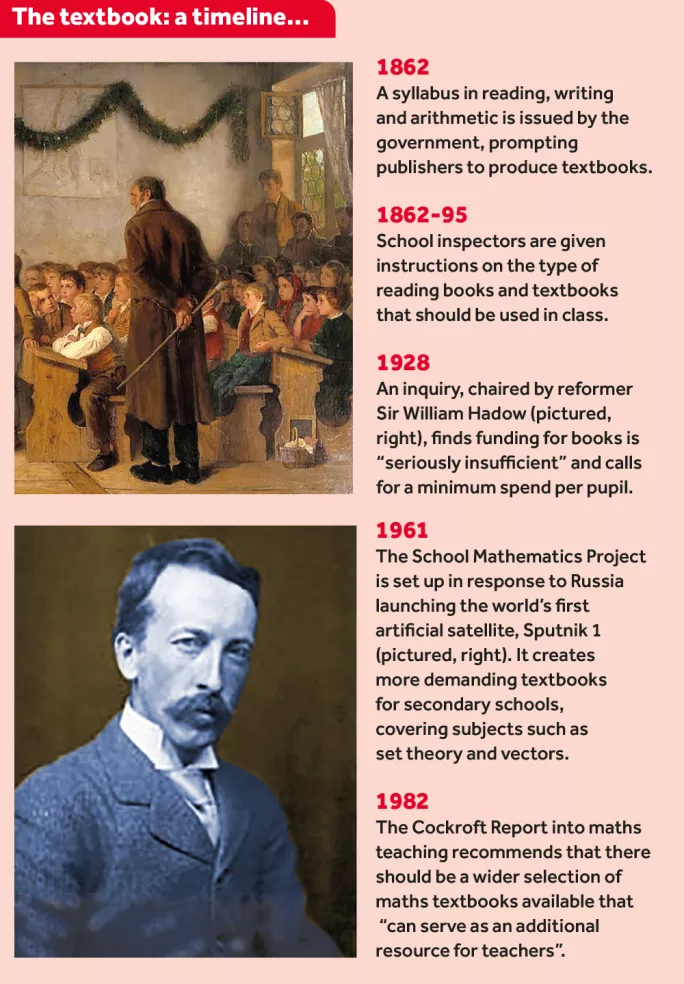

The pro-textbook policy drive began four years ago, when Elizabeth Truss, then a junior minister at the DfE, called on publishers to “help England fall back in love with textbooks”, saying they could liberate teachers from “reinventing the wheel”.

She said that their use had fallen out of favour owing partly to a progressive philosophy that viewed textbooks as “regimented, old-fashioned and stifling creativity”.

But Truss also said that textbooks had sometimes been too focused on teaching to the test, and consisted of “uninspiring content”.

A year later, Nick Gibb exhorted publishers to make more of an effort to overcome the “astounding” gap in textbook use between England and high-performing countries.

The use of textbooks varies greatly by subject, with maths teachers and modern foreign language teachers most likely to say they use them frequently. But even in those subjects, teachers believe that they will use textbooks less often in the future.

Secondary teachers are more likely to use textbooks in most lessons (15 per cent) than primary teachers (6 per cent).

Wasted effort

Advocates of textbooks often argue that their usage can reduce teacher workload. John Blake, head of education at the Policy Exchange thinktank and a former teacher, sees this as one of the most pressing arguments in textbooks’ favour.

“I think there is a peculiar reluctance among teachers to draw on textbooks, although we know they are a key feature of successful teaching elsewhere - and they reduce workload,” he says.

“There is a huge amount of workload that teachers seem to think is a necessary and vital part of their job. But I don’t think it is massively educationally effective or useful. I don’t think you need to have identikit lessons, but greater and more regular reliance on textbooks - the majority of time for the majority of teachers - would save time and would mean a more consistent level of educational quality.

“In general in English education, we ought to be using more textbooks, more often.”

But some teachers remain unconvinced that using textbooks could contribute to a reduction in their workload, since they still need to find activities that are tailored to their class and may have to repeat topics.

For Morgan, the workload involved in seeking out online resources is minimal. “I know where to go online and it takes two minutes,” she says.

And Ben Davey, assistant head of Bridge Learning Campus in Bristol, who teaches Spanish and religious studies, does not see the creation of lessons as an onerous task, but something he enjoys and in which he takes professional pride.

Perhaps one of the difficulties of working out why textbooks are sometimes seen as expendable in this country when budgets are tight is that few researchers are questioning it. “One of the things that is very noticeable is that research on textbooks and their use is very unfashionable in England,” says Oates. “It’s almost as if it’s a grubby thing to do, but you wouldn’t find that attitude in Finland or Singapore.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters