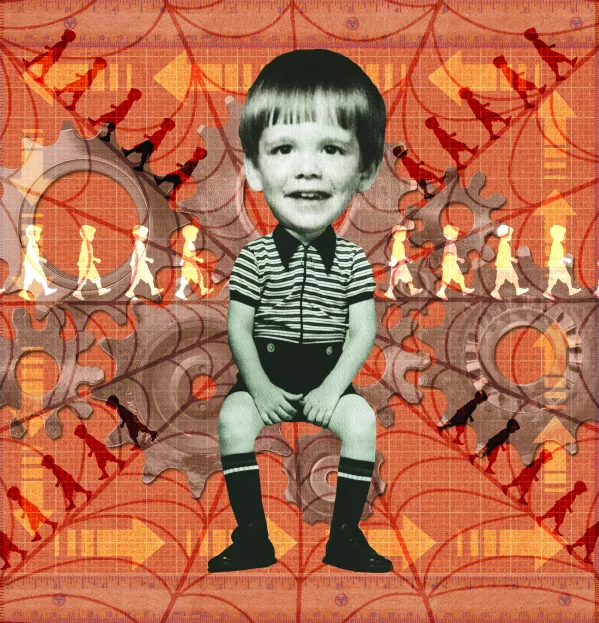

School transitions: why we need to talk about them

Think about how unsettled people feel in an airport. It’s no wonder: you’re disorientated and rushed; the ropey food is overpriced but you can’t go elsewhere; you get ordered to remove items of clothing and go through full-body scanners in front of onlookers; you are corralled into sweaty holding pens, where you fret about whether you’ve forgotten something; and loudspeakers bark unintelligible orders at you.

But once through the other side of this weird, discombobulating limbo, says early-years expert Aline-Wendy Dunlop, you feel like a “real person” again - because you’re returned to familiar surroundings, where you are back in control.

The airport experience, says Dunlop, is a classic example of a “transition” - and is a fine reminder of what it’s like to experience educational transitions: those liminal phases along our long and winding paths through formal education that move students into new and often very different arenas, where even those who once thrived can find themselves struggling.

The transition that has traditionally received most attention has been that difficult jump from primary to secondary school, when 11- and 12-year-olds - who may be accustomed to working with a single teacher in compact, friendly surroundings - are suddenly expected to flit between umpteen teachers in a hangar of a building, where every corridor seems fraught with danger.

But for four- and five-year-olds, the move to school from nursery can be equally daunting. Their daily surroundings change dramatically in scale and style - for all the talk of play-based learning in primary schools, many parents still comment on just how formal it seems compared with nursery. Not only that, but the range of maturity between children can be vast: you may have children in the same class whose birthdays are a year apart, meaning huge variability in cognitive development.

Different approaches

There are, however, many other transitions that can have a dramatic impact on a child’s education, says Dunlop. And she should know - she will shortly publish landmark research on transitions, based on 14 years of tracking children’s progress through the Scottish education system, from nursery to life after secondary school.

Transitions, she explains, are not merely those big leaps from different stages of school education. They may also occur from one day to another, or even within the same day - perhaps from one classroom to another very different one, or from the comfort of home to the stress that school represents for some children every day.

And a transition that can be “absolutely mindblowingly influential” is that from one teacher of the same subject to another - as anyone who struggled with, say, maths one year, only to fly high in that subject the next year can testify - and success often comes down to whether a pupil clicks with an individual teacher.

So, says Dunlop, the idea of transition as a linear process is false: in fact, “it’s like a web”, a highly complex multitude of sudden events and long-term processes that can make or break a child’s experience of education.

And yet, for such an important concept in education, Dunlop says the research on transitions is relatively scant. Perhaps that is why some ideas around transitions endure, despite experts in this area discrediting them long ago.

‘Readiness’ myth

Most notable is the notion of “school readiness”. It’s an “insidious idea”, says Dunlop, that encourages a “checklist approach to milestones”, by favouring a rigid “deficit model” of transitions.

“You’re checking what the child can and can’t do - [for example] if they’re going to have to sit on a chair or recognise their name.” This, says Dunlop, puts pressure on nursery staff to adopt an approach of “we’d better teach them that before they go to school”, even if the child is not ready for it.

Leading researchers were challenging the idea of “school readiness” decades ago, says Dunlop, yet “still it regurgitates”. She would prefer transitions to be viewed “not as a hiatus, but as a space in which all sorts of new things can happen”, with educators taking the attitude of “here’s a superb opportunity” and focusing on what a child brings to a school, not what they lack.

She recalls one diminutive girl who, upon starting primary school, struggled to work a pair of scissors, but had a talent for making people laugh. A friend would cut things for her, and they would laugh together about how they jointly muddled through this task.

But, with the focus in the class being on whether she had the motor skills to use scissors, she became embarrassed about her perceived shortcomings, rather than glowing with pride about what she brought to the class. It is an example, explains Dunlop, of how a subtle shift in emphasis - celebrating what the girl could do rather than homing in on what she could not - can help a child get off to a good start at primary school.

One idea Dunlop favours, then, is new primary pupils bringing in scrapbooks or posters about their interests and families - other children love to pore over these, and it fuels pride in the creator of this work of art, as well as helping teachers get to know each child.

Dunlop was a driving force behind a University of Strathclyde conference in May that drew transitions experts from as far afield as Canada and New Zealand, and which also saw the publication of the Scottish Early Childhood, Children and Families Transitions Position Statement. One such expert was Sally Peters, an associate professor and head of Te Kura Toi Tangata Faculty of Education at the University of Waikato, on New Zealand’s North Island, who has led a number of research projects on transition experiences, and specialises in children’s development from birth to the age of eight.

In her country, transition to primary school has worked differently: children tend to start school at the moment they turn 5, meaning that teachers are welcoming new pupils throughout that first school year. This, of course, offsets some concerns about differing levels of maturity, but it has been known to create other problems. Peters recalls, for example, cases of children starting at the same time as a school show, meaning their first experience of school was practising going into the hall and out again in an orderly fashion - hardly the best introduction to daunting new surroundings.

Peters can also, however, cite plenty of better examples of nursery-primary transition. There were the older primary children who made films about what it was like going to school and what to expect, or who came to talk to the nursery children and bring books and other items they were likely to encounter in school. Or there was “Lunchbox Friday”, when children made lunch themselves so that they felt more positive about school food and were more likely to eat it.

The keys to successful transition, believes Peters, include: school staff learning about children’s interests and competences; stronger links with parents; teachers developing cultural knowledge about their pupils; and carrying out an audit of resources, to reflect that not all children come from same type of family.

A crucial point, says Dunlop, is that “a good transition for you is different from a good transition for me”. In other words, the old idea of a universal approach to transition no longer cuts it, as its success depends on many things, which will differ from child to child. Her research has also found that transition “isn’t just about continuity and discontinuity” of a child’s experience, as it also depends on other factors such as how much “agency” each child has.

This is where the expertise of Kate Wall, a University of Strathclyde professor and expert on “student voice”, comes in useful.

“In transition, you are homogenised as a group of incoming children and parents in the school community,” says Wall, another speaker at last month’s event. Yet, while some families know a lot about school, others know nothing, so it makes no sense for a school to adopt a uniform approach to transition.

It is not unusual, Wall finds, for a child who was confident in nursery to feel “way out of their depth” in primary school, and voiceless in a way they are not used to. She pointed to an “outstanding” nursery that reacted quickly to children’s areas of interest: if, for example, they expressed an interest in cars, a few hours later they could be out visiting a garage.

School, however, could be a different sort of place. Wall cited one where pupils were consulted about the length of lessons they would prefer; ultimately, however, the headteacher had already made a decision and was merely paying lip service to the idea of student or pupil voice. Wall says schools need to be honest with their pupils and, if an idea they have for their school is impractical, they should at least be told why rather than it being dismissed out of hand.

“Just because they’re 5 does not mean they shouldn’t be talked to like they have rights,” says Wall.

All in the family

It is not only the child who has to get their head around a transition - their parents are affected, too, says Marion Burns, an Education Scotland inspector of early years and primary, and a researcher at the University of Strathclyde.

“It’s the family that’s in transition,” she says.

That view was backed up at last month’s conference by a nursery teacher, who said the move to primary school is “such a massive transition for families”, largely because they do not tend to have the relationships and frequency of contact with primary teachers that they enjoyed with nursery staff.

“When they move to school, I feel like they’re back out on their own again … and nobody’s taking an interest in what’s happening in the family home,” said the nursery teacher.

Burns says that “something bizarre happens” even when children are moving from a nursery to a primary on the same campus: families find that the climate is “not participatory at all” in the way they had become accustomed to in the nursery next door. There is still a tendency of “one-way traffic - it’s all happening to the parent”: so communications to parents from their child’s school are often imparting information rather than encouraging dialogue.

Some schools, however, are more attuned to the wealth of knowledge and skills in families and, says Burns, strive to tap into that. One headteacher she cited took a very different approach to communications with parents, talking of “equal partnerships” and asking parents: “What do you bring to the table?”

Yet, Burns finds that preparation for transition - whatever form it takes - is just not the priority that it should be. Schools might, for example, come out to visit children at a nursery that will be funnelling many children their way, but Burns had heard of schools that said they could not do the same with a private nursery with only one future pupil at the school - a sign, fears Burns, that awareness of the importance of transitions still leaves much to be desired.

Meanwhile, Dunlop poses an even more fundamental question about transitions between stages of education: why do we even have them at all?

In Scotland, Curriculum for Excellence was supposed to create a seamless educational experience from 3-18, but no one would claim we are anywhere close to that in practice. Instead, says Dunlop, educators are still working around the big breaks - from nursery to primary, from primary to secondary - that are a hangover from the “Victorian school system”.

“We’ve got something in our systems that just embeds transitions,” she says.

For now, then, Dunlop says we have to work in a less-than-ideal world where such transitions are a reality, like it or not. In the meantime, she has two simple mantras for educators to help smooth the way for children and their families: transitions should be about “continuity without sameness” - but also “change without shock”.

It’s just a shame we can’t do something similar about the security checks at Edinburgh airport.

Henry Hepburn is news editor of Tes Scotland. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

This article originally appeared in the 7 June 2019 issue under the headline “Lost in transition”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters