Education always comes down to numbers. Behind every parent’s query about their child’s progress sits an elaborate equation made up of teacher-student ratios, assessment grades, minutes of contact time, size of friendship circle, number of awards and plenty of other small, numerical metrics accumulated from class WhatsApp groups and Facebook posts.

Behind every government platitude are measurements of progress, standardised assessment scores, budget bottom lines, staff numbers, efficiency metrics and many more elaborate data-centred ways of trying to assess a school.

But which digits most occupy teachers’ minds and haunt their dreams? I can’t talk for us all but, for me, it is the number of students in each lesson that will attempt to mess me up.

Let me explain. I am what you might call an experienced teacher: 15 years in the job, leadership roles at head-of-year level, lots of pastoral experience and a mixture of schools under my belt. One or two students playing up is fine. I can deal with it. They are back in their box before they have even tried to ping the elastic band at Louisa’s head or kick the standing legs on Ali’s leaned-back chair. I’ve been there before. I see the signs. I have the relationship with them. It’s easy.

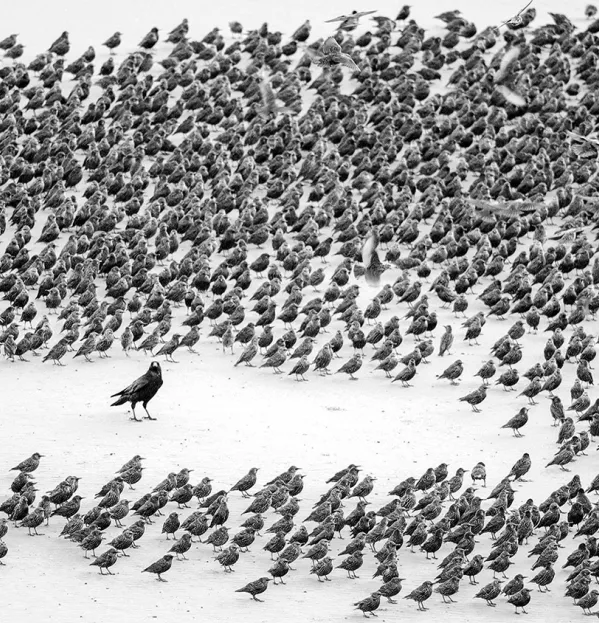

But add in another teenager trying to mess things up and things get tricky. It’s hard to monitor them all at once, and with more numbers come more possibilities. Add yet another, or even two more, and I have a crisis on my hands. Once you hit five children trying to mess you up, you stand very little chance of stopping them.

So, I have started scanning my class lists. I highlight lessons that I know are going to be an issue. And I try to work out a plan.

Breaking them up across the class does not work - it just adds to the challenge if they choose projectiles. And if it’s low-level disruption they are after, I have essentially just played into their hands: there is a cell of discontent in each area of my classroom.

Sanctions don’t do much either. These are children who know how to take a sanction and wear it with pride. When there are two of them or fewer, the relationship between us is strong enough and the peer pressure weak enough to use other methods. When there are five? My relationship with them does not mean a thing to them.

So, what to do? By my reckoning, the only option is to divide and conquer: we need to break those classes up and change them regularly if new dynamics emerge. We can’t let them get to a group of three, four or five.

Does this strategy work? The timetabler and head of department’s faces, when I suggested it, spoke volumes. But I live in hope of collective action. I am lobbying my colleagues. I am hoping the more people I get behind my cause, the more chance I will have of messing up the timetable to stop my students messing me up.

Luke Marsden is a secondary school teacher in the South of England

This article originally appeared in the 22 January 2021 issue under the headline “Once you’re outnumbered, you’ll always be outgunned”